A World That Never Was: 5 Oddities From Ancient Maps

Maps through the Ages

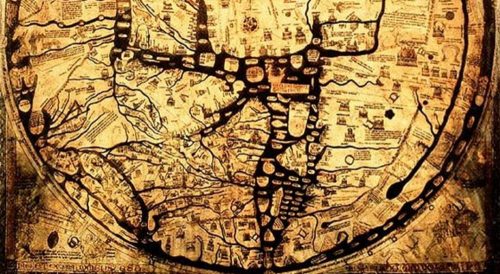

Maps are incredible tools that have evolved over the ages as society has made technological leaps and bounds to arrive at today’s modern cartographic standards. One of the oldest maps still in existence is the Babylonian World Map carved into a stone tablet. The tablet dates to around 600 B.C. Another attempt at mapping the Earth we have evidence of is the Roman scroll map. At just under a foot high and over 22 feet long, it is hardly an accurate map.

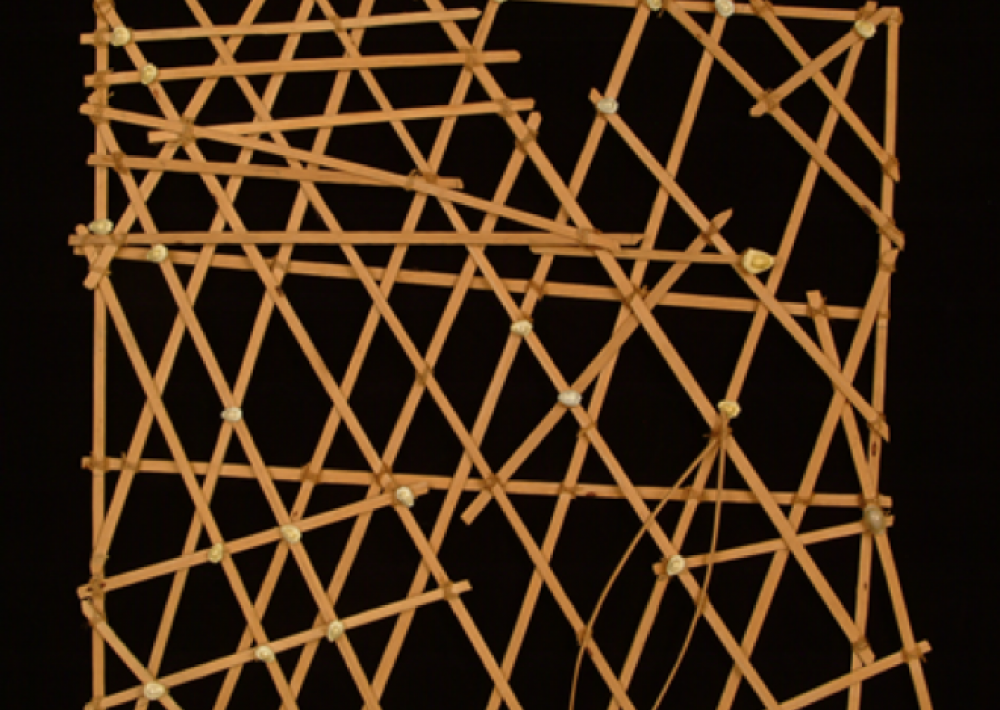

Ptolemy was a Roman who made great strides in developing some of the first geographic methods. Ptolemy is credited with creating latitude and longitude, using his method to plot over 8,000 known location in the Roman empire on different maps of his time. He was one of the first cartographers to worry about geographical accuracy not only in places relative location to each other but also to the stars, taking into account Earth’s spheroid shape and creating some of the earliest attempts at geographic projections. From Ptolemy’s initial geographic endeavours, we can see a non-linear evolution since then, with T-O maps, Micronesian Stick Charts, and many other unique chapters along the way to today’s modern satellite-based mapping.

Although these older maps contain valuable insight into the time period in which they were created, they often come with inaccuracies and anomalies. Some examples below feature sea monsters and islands that never existed, and many other interesting features we can look back at with our modern understanding of the world. In this article, we will be taking a look at 5 of these prominent and entertaining cartographic oddities:

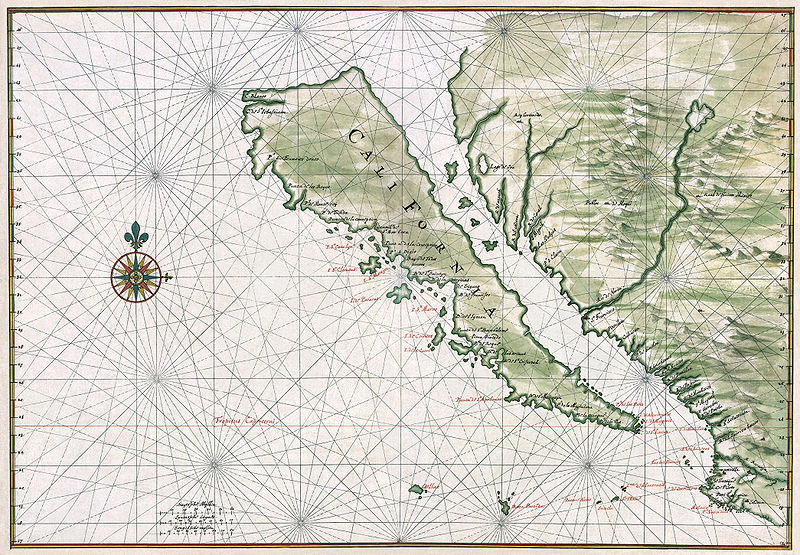

The Island of California

In ages of early exploration, “California” was rumoured to be a lush tropical island off the west coast of North America. It appears that for all intents, these stories referred to what we now know as the Baja California Peninsula, a 1200km long peninsula at the south-west corner of the state of California and along the north-west coast of Mexico. However, in many maps from the 1500s, the “island” of California was separated from the mainland of North America. The channel was drawn roughly the same width as the modern-day Gulf of California, varying from 100-200km. While this peninsula may be a popular place for a beach vacation, it is not an island.

This revelation may come as a surprise to Hernan Cortez, the famous Spanish Conquistador. Cortez sent three ships to discover the Island of California in 1532. When they disappeared without a trace, another expedition went in 1533. The second expedition never reached their destination either. However, in 1539 Francisco de Ulloa explored both coasts of the peninsula to the mouth of the Colorado River at the head of the gulf, concluding that it was not an island.

The Australian Inland Sea

The map below was included in Thomas Maslen’s 1827 book The Friends of Australia. It depicts a vast river system flowing from a sea in the continental interior to a supposed outlet in the north-west. Many explorers of the time proposed Australia would be like the unknown places they had previously discovered. Its geologic features were thought to consist of an interior mountain range with fluvial systems cascading downwards towards the sea, joining one large river carrying out to the ocean. They made maps containing these features, and for a few decades, it became a common misconception about Australia. As explorers got further into Australia’s interior, they found the barren, dry outback where they were supposed to locate a massive inland sea. Eventually, they determined that the sea must not have existed and that earlier maps were incorrect.

Sea Monsters Everywhere

Tales of adventures from the high seas in early times often included stories of enormous sea monsters swallowing ships whole, disappearing in foggy weather or overnight, never to be seen again. Cartographers imaginations became filled with visions of incredible creatures that could take down ships with a swift tentacle or sea serpents of mythological proportions.

As you can see, this map of the North Sea contains epic numbers of sea creatures that are mean and menacing and responsible for all of the missing ships throughout the ages. With this many monsters – how could any ship make safe passage?

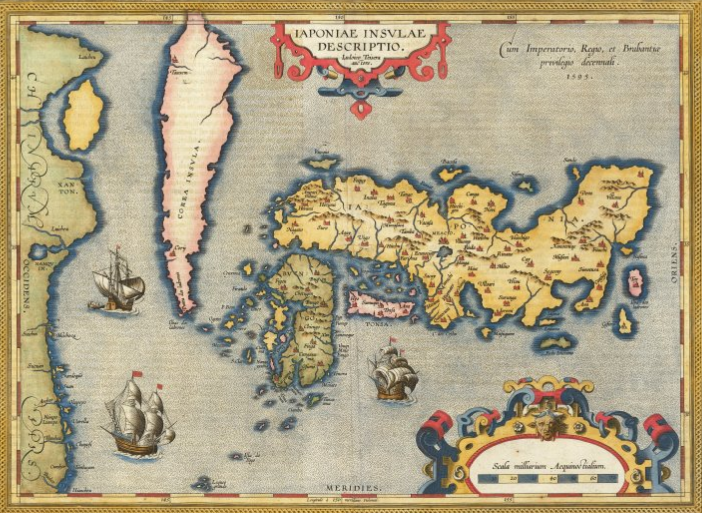

The Island of Korea

Another place that is mistaken for an island on maps throughout the ages is the Korean peninsula. Jutting out for 1100km from mainland Asia, little was understood of the Korean peninsula by the early exploring Europeans. The border between North Korea and China does trace two large rivers at the eastern and western extents, the Yalu and the Tumen, which could have led to the misconception.

It is strange when looking at the maps to see such a well defined Japan in such contrast to a Korea that doesn’t even closely resemble what we now know to be its shape. There seems to be a pattern among early explorers like we saw in California, where speculation and incomplete exploration resulted in inaccurate maps.

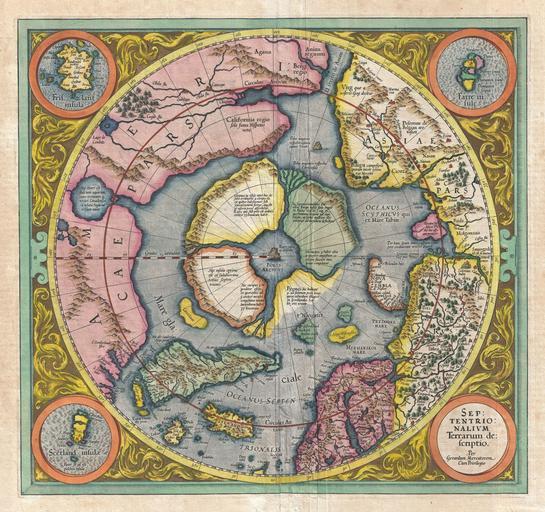

Rupes Nigra

Did you know that explorers believed the Earths’ magnetic north inclination was due to a gigantic magnetic rock located at the north pole? This rock was often depicted on maps as a large black mountain at the geographic north pole. It was said to be 33 leagues (180km) across and stand directly at the top of the globe, surrounded by giant whirlpools that drained the Earths’ oceans into its core. It was first included on Mercator’s Arctic projection, as seen below:

These whirlpools were said to be inescapable for those who dared to venture too close and had previously been written about by Mercator in 1577 in letters to the famous mathematician John Dee. This ‘discovery’ conveniently provided a solution for why compasses point north. The first modern explorers reached the north pole in the early 20th century. As we now know, the northward orientation of compasses is due to the magnetic field generated through complex processes within the core of the planet and not by giant magnets situated at the poles.

Thanks, NASA!

While looking at these old maps may be fun and entertaining, it also demonstrates how far we have come in our ability to understand and quantify the planet. Thanks to modern navigation equipment and satellite imagery, there are no longer debates about cartographic features. Islands that don’t exist are no longer on maps, and (almost) nobody has to worry about their boat getting capsized by a large monster from the deep anymore.

Very interesting! Someone should write a fiction about an alternate Earth where these places actually exist 😉