Digital construction mandates are standard across the G7 and many other developed nations. Canada remains the exception — and without BIM and digital twins, its ambitious housing push risks failure.

Canada is racing to build houses — and running straight into the same wall it’s hit for years.

The federal government’s new Build Canada Homes initiative, launched in September with a $13-billion fund and access to 88 federal sites, promises nothing less than a housing revolution. Ottawa says modular and mass-timber construction can double delivery “at speeds not seen in generations.”

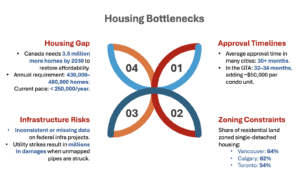

But promises don’t pour concrete. Canada is completing fewer than 250,000 homes a year, while the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) warns it needs 430,000 to 480,000 annually to restore affordability — nearly double today’s pace.

And it’s not just volume. Canada is the only G7 country without a national mandate for even Building Information Modeling (BIM), let alone digital twins.

The UK, Germany, and Italy have all mandated BIM in public projects, while France and Japan have national frameworks that steadily push adoption. Even in the U.S., federal agencies like the GSA and Army Corps require BIM on major projects.

Outside the G7, BIM mandates are already national policy in Singapore, South Korea, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and Chile. On digital twins, Singapore’s Virtual Singapore remains the global benchmark; China has made them a national priority under its New Infrastructure plan; and European countries, such as the UK, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, and Norway, are embedding them in infrastructure and public works. Together, these examples highlight how peers are treating digital infrastructure as seriously as physical infrastructure.

Approvals: The First Bottleneck

“The government has been slow to digitize and create mandates for this. We’ve been raising the issue for a decade now with very little progress,” Richard Lyall, President of the Residential Construction Council of Ontario, had told me in an interview last year.

Lyall, who has been advocating for solutions to Ontario’s housing crisis, argued that technology can be a key lever for boosting supply — giving developers, architects, and engineers the ability to model and adjust projects in advance, helping accelerate delivery and improve build quality.

But a year later, nothing has changed. The Canadian Home Builders’ Association’s 2024 Municipal Benchmarking Study reveals that approvals are taking over 30 months in many municipalities. In the GTA, timelines now average 32-34 months, adding roughly $50,000 in costs to every condominium unit before a single brick is laid.

Delays pile up because planners are forced to shuffle paper maps and siloed databases. Public consultations drag on because residents are asked to imagine impacts they can’t actually see. Departments that don’t share systems issue approvals as if they’re passing files hand-to-hand down a corridor.

Digital twins have become proven tools worldwide, helping governments and developers model density, infrastructure loads, and design changes in real time. Applied to planning, they can show how zoning changes, traffic impacts, or water systems will play out — compressing processes that once took years into weeks.

In Canada, however, their use remains limited, largely because there is no mandate or coordinated framework to integrate them into the approval process.

What Is a Digital Twin?

A digital twin — sometimes referred to as a digital mirror or replica — is a dynamic model of a physical asset that updates in real-time. As buildingSMART explains, “Linked to each other, the physical and digital twin regularly exchange data throughout the plan-build-operate-decommission lifecycle. Technology like AI, machine learning, sensors, and IoT facilitates dynamic data gathering and real-time data exchange.”

A digital twin is not just a static 3D model. It is a living system that continuously exchanges data with its physical counterpart, showing how assets behave under different conditions and how they interact across networks — from transportation and water to housing and energy.

In the housing context, digital twins can simulate entire neighborhoods — testing the impact of new density on traffic, utilities, or stormwater systems before a single permit is issued. They enable governments and developers to transition from guesswork to evidence-based planning, saving time and minimizing costly mistakes.

However, according to a CSA Group 2022 study Digital Transformation in the Canadian Built Asset Industry, “Canada’s built asset industry lags behind other countries in the adoption of digital technologies. Fragmentation within the industry and a lack of coordination across sectors have slowed progress, preventing efficiency gains and innovation that digital transformation can deliver.”

This warning, delivered three years ago, remains unanswered. Canada still lacks the framework to scale digital twins nationally.

Alex Penner of Midwest Surveys argued that geomatics and digital delivery must sit at the core of the country’s infrastructure push — without a national framework for BIM and digital twins, those ambitions risk being built on shaky ground.

Zoning and Land Use

Even before approvals, zoning laws choke supply. The OECD’s Canada Economic Survey 2025 found that in Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto, more than half of all residential land was locked into single-detached housing — 64%, 62%, and 54% respectively.

That rigidity forces municipalities into lengthy rezoning battles to unlock housing supply. And community resistance is fierce. Without tools to demonstrate how density will impact traffic, water systems, or green spaces, mistrust flourishes. Everyone argues in the dark.

The result: housing supply gets pushed farther outward. Sprawl consumes vast amounts of farmland and increases commute costs, while inner-city affordability continues to erode.

Build Canada Homes may help with land and capital — but until zoning is digitized and tested in real time, approvals will remain a political brawl.

Infrastructure Backlog

Approvals also hinge on whether pipes, sewers, and transit can handle new growth. But much of that infrastructure is old, poorly mapped, or simply unknown.

The Auditor General’s 2021 audit warned that Infrastructure Canada lacked reliable data on the condition and performance of funded projects. More recent reviews — of the National Trade Corridors Fund and the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program — found the same problem: oversight systems existed, but performance data was incomplete or misaligned with long-term risks.

As Peter Srajer, an authority on underground infrastructure, said: “One of the biggest risks is the unknown — utilities that aren’t mapped, pipes that don’t appear on any record. Too often, you only discover them when a backhoe hits.”

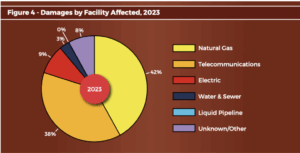

The scale of the challenge is striking. In 2023, nearly 10,000 cases of damage to buried infrastructure were reported in Canada as a result of excavation. Most of these incidents — nearly 80% — affected critical utilities, including natural gas and telecommunications, while about a quarter involved water and sewer lines. Excavation mistakes accounted for more than a third of the reported damage.

Those numbers may, however, understate the problem. The Canadian Common Ground Alliance’s Damage Information Reporting Tool (DIRT), which tracks such incidents, relies on voluntary submissions, meaning the real tally is likely much higher.

Digital twins could prevent much of this by mapping underground assets in advance.

Procurement: The Missing Link in Digital Delivery

One of the persistent barriers to modernizing Canada’s housing and infrastructure delivery lies in the procurement process. Current processes are slow, bureaucratic, and often misaligned with the urgency and scale of today’s challenges.

As Claudia Cozzitorto, a senior AECO industry leader in Canada and a member of the leadership team at buildingSMART Canada, explained: “Procurement must evolve to recognize and enable modern digital services and deliverables, such as Building Information Modeling (BIM), openBIM standards, and ISO 19650-compliant workflows.”

Innovations and advanced digital deliverables are already being implemented in public projects across Canada — but too often they remain isolated successes rather than becoming standard practice. Outdated specifications force project teams to work around legacy requirements instead of applying modern, more effective methods.

WSP’s Bryan Waller and Cheryl Trent made the same point: Canada’s procurement frameworks are out of step with international best practices. Instead of rewarding digital competency and lifecycle value, contracts often reinforce outdated requirements. Aligning procurement with standards such as ISO 19650, they argue, would reduce risk, improve outcomes, and enable projects to be delivered at the speed required by Canada’s housing crisis.

International examples show what is possible. The UK mandated BIM on public projects a decade ago, a single policy decision that spurred the development of industry standards, training programs, and a digitally enabled supply chain.

The State of Play in Canada

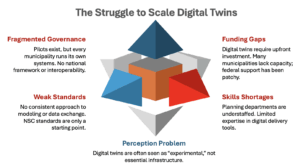

“The biggest roadblock is the lack of a common industry-endorsed framework for BIM and digital twin,” says John Hale, President of buildingSMARTCanada and Chief of BIM/GIS at the Department of National Defence. “This is something that the NRC has identified and is working with federal departments and industry stakeholders to improve. Without that framework, every department or project reinvents the wheel. That wastes time and resources and discourages industry adoption.”

Digital twin adoption in Canada is advancing, but patchy — Digital Ambition strategytouches on modernization, yet stops short of a national requirement.

A KPMG and Canadian Construction Association survey showed just 25% of firms felt competitive in technology, and only 23% made data-driven decisions. Cloud computing is widely adopted, but advanced tools like digital twins remain the exception.

Several barriers stand in the way: governance is fragmented, with municipalities running isolated pilots on different standards and platforms that don’t connect. Funding is another constraint — digital twins require upfront investment that many municipalities lack, and federal support has been inconsistent. Skills are also a bottleneck; planning departments are short-staffed and often untrained in emerging digital delivery tools. And perception plays a role: in many quarters, digital twins are still seen as experimental rather than as core infrastructure.

KPMG’s 2024 analysis concluded that government leadership will be crucial in establishing a collaborative ecosystem. Canada’s National Research Council has highlighted the lack of interoperability standards, while the National Standard of Canada introduced a baseline for “discovery and management” of twins — still a long way from scaled deployment – only in 2024.

“There isn’t a single agency or department with a mandate to drive this change,” Hale adds. “There is solid effort within several federal departments; however, we need to drive digital transformation across all levels of government. The challenge is leadership fragmentation. We have bright spots, but no single champion. That’s why buildingSMART Canada’s role as a neutral convener is so important.”

Imagining Canada’s Digital Twin

Carleton University’s Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) is prototyping an open-source digital twin platform for the country, designed to integrate housing, infrastructure, and environmental data. CIMS has already supported several housing initiatives across Canada, showing how digital twins can model growth, test designs, and improve cost management. Their “Imagining Canada’s Digital Twin” project goes further — building the foundation for a national platform that could scale across sectors.

The project has won several awards, including the Professional Research Award from buildingSMART International, which was recently presented. This marks the first time Canada has received an openBIM award — a sign of growing international recognition for its work.

The project demonstrates two truths: Canada has the talent and technical expertise to lead in digital twinning. What it lacks is political coordination to take pilots and scale them nationally.

“Success will only come through a multidisciplinary and collaborative effort. If governments, communities, and developers align, we can move from pilots to a shared national vision for affordable housing,” said Nicolas Arellano, Team Lead at CIMS and Director, Digital Built Ontario.

Ambition Meets Accountability

Build Canada Homes is the boldest federal housing program in half a century. Its ambition — doubling construction, mobilizing public land, reshaping supply chains — matches the scale of Canada’s housing crisis.

But ambition without execution won’t close the gap. CMHC’s 2025 analysis makes it plain: Canada must nearly double its housing output every year to restore affordability. That won’t happen if approvals take three years, zoning is locked in outdated maps, and infrastructure records are missing.

The story hasn’t shifted. Warnings from industry and researchers have piled up for years, but the bottlenecks persist. If Build Canada Homes cannot cut through the delays and modernize how we build, then its billions will buy only more frustration.

Be the first to comment