When Canadians dial 9-1-1 today, they expect to speak with someone who can send help. This voice-based system has served us for decades. But major changes are coming.

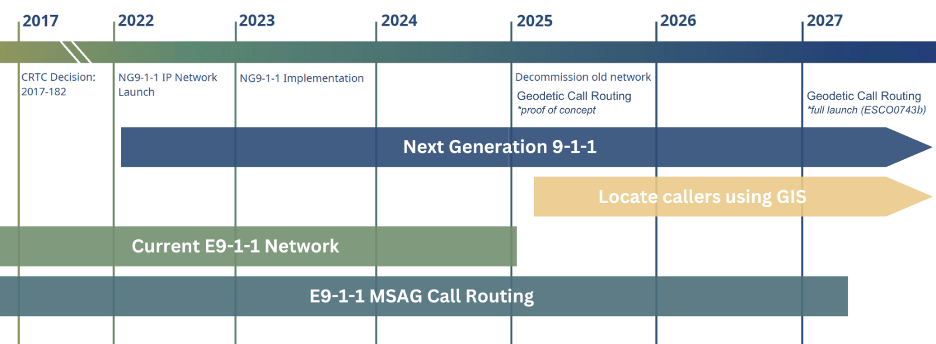

Canada is replacing its legacy emergency system with Next Generation 9-1-1 (NG9-1-1). Originally set for 2025 rollout, the comprehensive digital upgrade is now expected by March 2027.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) is overseeing the national rollout of NG9-1-1. As the federal regulator, it has set the timelines, technical standards, and compliance obligations for telecom providers and emergency response systems. While telecoms are upgrading the networks, municipalities and provinces are responsible for ensuring their geospatial data is ready to support the system.

This new system will handle not just voice calls but also text messages, photos, videos, and real-time geolocation data, and promises to enhance the speed and accuracy of emergency services.

Most people are aware of the shift from analog to digital communications, but many don’t realize the crucial role maps and location data play. Are Canada’s digital maps ready for this life-saving responsibility?

“People think of 9-1-1 as just a phone call, but what really matters is what happens after that call is made,” says Chris North, Principal, North GIS Consulting. “Accurate GIS data is essential to routing emergency calls — even more so than the phone call itself. If the data isn’t right, you’re not going to get help where it’s needed.”

A Matter of Life and Death

Think about calling 9-1-1 after a car accident or during a home emergency. Getting help quickly depends on responders knowing your exact location.

NG9-1-1 needs more than just good technology – it needs accurate data. GIS (Geographic Information Systems) data forms the invisible foundation: street networks, addresses, municipal boundaries, emergency service zones. When your call or text comes in, this determines call routing.

It’s a matter of life and death, literally.

The Canadian NG9-1-1 Coalition roadmap for Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs) outlines steps municipalities need to prepare their data. Communities must tackle data and staffing issues. GIS data must meet specific public safety standards for accurate routing. Esri Canada has also been stressing that GIS data must meet specific public safety standards for proper emergency call routing.

“NG9-1-1 is one of the most important — and overlooked — public safety transformations underway in Canada,” says Jonathan Murphy, CEO of GoGeomatics Canada. “It’s built on geospatial data, but we rarely talk about the people and systems behind that data. That has to change.”

When Addresses Fall Through the Cracks

One serious challenge in rolling out NG9-1-1 is the time lag between when development begins and when addresses are recorded.

North, a GIS expert who has worked with several municipalities on their NG9-1-1 transition, says this is a common issue across Canada. “You get into these weird gaps where a project starts construction, and it’s going to take four years to complete,” he explains. “They don’t actually assign those parcels until close to the end. So, for three years, there’s work happening on the ground, but it’s not in any system.”

This lag means that for a significant period — sometimes years — new developments are essentially invisible to the GIS datasets that underpin NG9-1-1 call routing. While the homes or buildings may physically exist, they aren’t yet part of the authoritative geospatial infrastructure.

That time gap isn’t just a quirk of development schedules — it reflects deeper issues in how municipalities manage addresses from start to finish. Most local governments lack a standardized address lifecycle process. Planning might create the address, but that doesn’t necessarily flow to GIS. And it certainly doesn’t flow to public safety right away.

As NG9-1-1 depends on accurate, real-time location data to route calls to the correct Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP), these address gaps introduce uncertainty. “There’s this big delay between activity on the ground and when it actually shows up in the data,” North says.

And in small or rural communities, where a single staff member might be juggling planning, GIS, and public safety communications, the challenge is even more acute.

A Tale of Two Canadas

Not all Canadian communities are equally prepared for this transition. Larger cities with established GIS departments, such Toronto and Vancouver, have already advanced significantly in mapping their streets, addresses, and emergency boundaries.

For instance, Vancouver has used the BC NG9-1-1 GIS Data Hub to align its mapping with provincial and national standards, ensuring their data will integrate smoothly with the new system. Even then the city underlines that a lot of work needs to be done: “Many agencies will need to work together to ensure that GIS data is as accurate, complete, and current as possible. Local Government Authorities (LGAs), which include Regional Districts, Municipalities and First Nations, must ensure that the required data is provided to the 9‑1‑1 telecom provider.”

On the other hand, smaller communities, which often rely on outdated mapping systems, are struggling. Many lack dedicated GIS staff; some still keep critical information in files rather than digital databases. The digital divide is real, and in emergency services, it could prove deadly.

“In smaller towns, GIS is often one person doing everything — zoning, planning, emergency data, even answering the phones,” says Jonathan Murphy, CEO of GoGeomatics Canada. “They want to get it right, but they’re already over capacity. NG9-1-1 is exposing that strain.”

The Canadian NG9-1-1 GIS Data Readiness Timeline outlines milestones that must be met by 2027. Municipalities must finalize geodetic routing and consolidate data from sources like road centrelines, address points, and PSAP/service boundaries — all validated to meet NENA standards.

The Unseen Challenges

For NG9-1-1 to function correctly, municipal data must meet what experts call “public safety-grade” standards. These include requirements for topology, coverage, and boundary matching to ensure that road networks, service boundaries, and emergency zones are accurately mapped and properly aligned.

The biggest headache for many municipalities is data consistency. When information formats differ across systems, standardization becomes tricky. If street names, addresses, or service boundaries don’t match across databases, emergency calls might be routed incorrectly or responders sent to wrong locations.

“It’s not just a technology problem — it’s a governance issue,” North explains. ““Different departments — planning, engineering, assessment — all doing their own thing, and no one’s coordinating this stuff and ensuring it all fits together the way NG9-1-1 demands.”

What adds to yet another layer of complexity is the fact that many local governments outsource their mapping needs to vendors, Murphy explains. This makes it a challenging task to ensure these third-party maps stay accurate and work with NG9-1-1 system. “It is essential for municipalities to harmonize their data to meet national standards, a process that’s both time-consuming and complex, but essential for the system to work,” he adds.

Cloud technologies can help keep data synchronized in real time — but only if the foundational data is accurate and structured.

What About the Z-Axis?

As NG9-1-1 expands to include text, video, and real-time geolocation, one critical element remains underdeveloped — vertical location.

“If you’re in a high-rise building, and the person says, ‘I am on the third floor,’ that’s still a problem,” points out Chris North. “The XY gets you to the address, but not the unit or floor. The Z-axis is still not well solved.”

North points out that vertical ambiguity becomes especially problematic in densely populated condo towers: “Where you get into trouble is high-rise residential buildings,” he explains. “You get a single parcel and now you have got 250 units and 25 floors. How do you define the relationship of those units and their access to the rest of the site? That vertical part is almost never in the GIS unless you have floorplans or internal maps.”

While smartphones now include barometric sensors that estimate altitude, most municipal GIS databases still lack floor-level mapping. Emergency dispatch systems also aren’t consistently equipped to use vertical data — even when it exists.

In the U.S., the FCC has mandated that mobile carriers provide Z-axis accuracy within 3 meters for most E911 calls in urban areas.

In Canada, Z-axis integration is still emerging. The CRTC has acknowledged the need for vertical Z-axis data, directing NG9-1-1 providers to explore necessary CAD and mapping upgrades with the Emergency Services Working Group (ESWG) assigned to monitor readiness.

Several municipalities — such as Guelph, Ontario — are already piloting enhanced GIS tools that could support future vertical location, in collaboration with organizations like Esri Canada. These efforts reflect a broader push toward Z-axis readiness, particularly in urban areas like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal.

Still, challenges remain. Barometric data can fluctuate due to HVAC or weather conditions. Most address datasets don’t include floor or unit geometry. And integrating that information into real-time dispatch workflows requires updates to data models, standards, and software used across PSAPs.

The People Behind the Maps

The data challenges are tough enough. But there’s another problem that keeps emergency planners up at night: people. Or rather, the lack of them. Finding and keeping skilled GIS professionals is a major bottleneck, especially in smaller communities. These specialists – who understand both mapping technology and emergency service needs – are in short supply across Canada.

“There’s no coordinated pipeline for GIS talent in the public sector,” North says. “We have got a national emergency system depending on location data, but no national strategy to grow and support the people who maintain it.”

Building local GIS capacity isn’t just a good idea – it’s essential for NG9-1-1 to work. “The NG9-1-1 Coalition keeps pushing for coordination between all government levels, but gaps in resources and training persist, especially outside major urban centers,” Murphy adds. The federal government has provided some funding to help municipalities upgrade their systems, but it’s unclear if this will be enough for all regions, especially rural and remote areas.

The Road Ahead

As NG9-1-1 approaches full deployment, Canada’s mapping sector is taking center stage in modernizing emergency response.

“We’ve got a national emergency system depending on location data, but no national strategy to grow and support the people who maintain it,” North says.

“We need to stop thinking of GIS as a back-office tool. It’s public safety infrastructure now,” adds Murphy. “It’s not enough to prepare the maps — we need to prepare the systems and people too. Otherwise, we’re building a next-gen system on yesterday’s data.”

NG9-1-1 goes beyond emergency calls. It’s laying the foundation for smarter cities, more responsive public services, and resilient communities.

The deadline is coming. The maps are being prepared. The question is whether every Canadian community will be ready when the call comes.

Be the first to comment