What happens when geospatial stops following and starts leading? That’s the question Dr Nadine Alameh posed to the audience during her keynote at GeoIgnite 2025 in Ottawa. She urged the geospatial community to rethink its role — not as a support function, but as a force driving bold decisions, intelligent systems, and real-world change.

In this wide-ranging conversation, Nadine shares what it takes to unlock that future: letting go of rigid definitions, embracing generative AI, collaborating across disciplines, and investing in the tools – and people – who will shape the next era of geospatial intelligence.

Excerpts:

Nadine, in your keynote, you challenged the geospatial community to stop reacting and start driving change. What exactly does that look like?

For a long time, geospatial has been positioned as a supporting technology – something that reacts to events, maps outcomes, or analyzes the past. But what if we flip that narrative? What if geospatial becomes the engine that drives decisions proactively, the foundation upon which we build smarter cities, predict disasters, manage our food systems, and tackle climate change before it strikes?

Driving change means refusing to be boxed into outdated definitions of what our field does. It’s time we reimagine our role – not just as mapmakers or analysts, but as architects of intelligent systems. With the rise of AI and cloud-native tools, we now have the capabilities to act faster, scale bigger, and make deeper impacts. But we have to be bold. We need to own our seat at the table, not wait to be invited.

You have talked about the importance of letting go of rigid definitions in geospatial. Can you explain why that’s so critical now?

Our world is too complex for silos. Historically, geospatial has been defined very narrowly – remote sensing, GIS, cartography. But those labels don’t reflect how geospatial knowledge is actually used today. We need to get comfortable with blurred boundaries, because that’s where the innovation is happening.

When I say let go of rigid definitions, I mean we have to stop protecting territory and start building bridges – with computer scientists, with domain experts in agriculture or defense or healthcare, with data scientists, policy makers, and user communities. We have been building bridges across disciplines for years, but now is the time to accelerate that work and be more deliberate about it. Innovation happens in the spaces between fields, and we need to lean into that with urgency and intention.

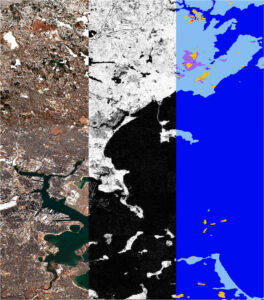

Generative AI is a great example. When we start training LLMs on satellite data or using AI to generate future land-use maps, we’re creating entirely new ways of reasoning about space. That’s geospatial – just not the kind we were trained in. So we need to open up our mindset and recognize that our value lies not in a job title or toolset, but in how we help people understand and act on the world around them.

What role do today’s technologies – especially AI and cloud-native platforms – play in transforming the way we work?

They are accelerators. In the past, we talked about building systems that could respond to change in weeks or months. Now, with the right infrastructure, we’re talking about minutes – even seconds. Cloud-native architectures let us scale globally from day one. AI gives us new ways to extract meaning from messy, unstructured, constantly changing data. Together, they are reshaping the entire lifecycle of decision-making.

We are also moving from query-based systems to reasoning-based systems. From static maps to dynamic, on-demand knowledge layers. You can ask an AI system: “Show me where urban expansion will most likely intersect with flood zones in the next 10 years,” and it can generate a probabilistic map based on satellite data, topography, and climate models. That kind of capability turns our data from a record of what’s happened into a tool for shaping what’s next.

But here’s the caveat: tools aren’t enough. And neither are people, unless we also get the data right. Data is the foundation of decision-making, and it needs to be FAIR – findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable – and above all, trusted. Without that, even the most advanced tools or talented people can’t deliver real impact. That’s why I keep emphasizing investment on three fronts: in tools, in data, and in human capital.

We need to equip the next generation not just with technical skills, but with the vision to ask the right questions, the responsibility to work with data ethically, and the courage to challenge how things have always been done.

As we bring AI into the geospatial world, especially with large language models, how close are we to building what you have called a ‘queryable Earth’?

That’s the next frontier, and it’s closer than we think. Traditional LLMs are great at dealing with words, but they’re not built to understand geography. Our data isn’t just textual – it’s spatial, spectral, and temporal. If we want AI to reason about the planet, we need to train models that can actually “see” the Earth.

That’s why we’re seeing efforts to build foundation models trained specifically on Earth Observation data. Projects like Clay, Earth Genome, and IBM’s TerraMind are pushing this frontier, developing models that can reason about land use, environmental change, and planetary dynamics with a depth we have never had before. They can look at a region and tell you what’s changed, why it matters, and what’s likely to happen next. That’s a massive shift from using AI to answer questions like a chatbot to using it as an analytical partner that understands our environment.

We are laying the foundations right now. But it will take continued investment, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a mindset shift – from treating geospatial as a dataset, to treating it as a language AI needs to speak fluently.

So, where do you see Gen AI + geo having the most impact?

Everywhere – but especially in areas where decisions are urgent and data is overwhelming. Think disaster recovery, national security, climate resilience, public health, agriculture…

Let’s take wildfires. Today, we can use satellite imagery and AI to track fire perimeters, map burn severity, and assess damage. That’s important. But imagine going further – using GeoAI to identify which buildings to rebuild first, where people can safely return, and which communities are most vulnerable. That’s what it means to go from awareness to action.

Or in food systems — AI-powered platforms can detect changes in land use like new plantations and link that with water quality, disease outbreaks, or biodiversity loss. That’s how we start connecting the dots across domains.

We already have these capabilities in pockets. The next step is scaling them, standardizing them, and making them repeatable and accessible to decision-makers across sectors.

What are some examples or projects that excite you right now in the GeoAI space?

There are so many – and they span the entire stack, from tools to foundations to applications.

On the tools side, I love what LuxCarta is doing with AI-powered 3D mapping. Their platform automatically extracts roads, building footprints, and vegetation to generate high-res, interactive maps – and it’s all customizable.

Then there’s Danti – they are fusing satellite imagery, sensor feeds, social media, and news sources into one multimodal AI interface. You can ask it plain-language questions and instantly get situational insights.

I am also fascinated by the foundational work happening – like Clay’s vision of a queryable Earth, Bedrock Research is building a cross-modal foundation model that integrates satellite, radar, and sensor data in real time, Zephyr is pushing spatial reasoning in LLMs, making them aware of physical location, not just language.

On the application front: Through Sensing detecting forest degradation, Avineon’s wildfire recovery dashboard, Sparkgeo working on biodiversity net gain, Tera Analytics simulating environmental futures, Clark University forecasting land cover change, and Crosswalk Labs improving emissions modeling with real-time AI agents.

What excites me is that none of these are just academic projects. They are practical, scalable, and grounded in real-world impact. That’s the power of GeoAI done right.

There’s also been a lot of activity from the tech giants in this space. How do you view the role of these “big players” in shaping the GeoAI landscape?

I think it’s incredibly exciting – and necessary. When companies like IBM, Google, and Microsoft start investing heavily in GeoAI, it validates the importance of this intersection. But what’s even more exciting is how they’re doing it.

Take IBM’s partnership with ESA. They have released one of the best-performing open-source generative AI models for Earth Observation. This model understands nine types of EO data and can even generate synthetic training data by reasoning across modalities. You can ask it to consider land cover dynamics when mapping water bodies. That’s spatial reasoning at a whole new level.

Google’s Geospatial Reasoning tools are equally promising. Starting with population and mobility models, they’re now extending that work to satellite and aerial imagery. Developers can use Gemini in Google Earth to build data layers with no code. That kind of accessibility could be transformative for small teams and communities.

Then there’s Microsoft’s Copilot with NASA. It helps users query and synthesize NASA’s vast Earth science data. Ask it how a hurricane affected Sanibel Island or how the pandemic changed air quality, and it pulls real answers from real datasets. It’s making complex data conversational.

These platforms aren’t just building apps – they are enabling ecosystems. Cloud-native environments, open-source models, accessible APIs. That’s powerful. But it’s on us to engage critically, ensure equity, and make sure these tools reflect the needs of real users. That also means being vigilant about how these technologies are used – ethically, transparently, and with safeguards in place. As we push the boundaries of what’s possible, we have to ensure the outputs are not only innovative, but trusted and responsible.

That brings us to partnerships. You often talk about breaking out of silos. How important is cross-disciplinary collaboration in driving GeoAI forward?

It’s everything. The problems we are trying to solve – from climate to defense to food security – have never come labeled “geospatial.” But now, that reality is more obvious – and more urgent – than ever. So our solutions can’t be siloed either.

We need to work across verticals, across domains, and across cultures of thinking. That means data scientists sitting with farmers, AI engineers working with emergency responders, and policymakers listening to communities. It means co-designing solutions that are meaningful, not just technically impressive.

And it means investing in people who can bridge those gaps. The next generation of geospatial leaders will need to understand data science, speak both spatial and statistical, and navigate cloud and community. And above all, deliver real impact within their domains.

What does meaningful collaboration look like to you that is key to unlocking the potential of GeoAI?

To me, collaboration isn’t just a checkbox – it’s a mindset, and an investment. It means breaking down the traditional silos that have kept innovation, research, and policy too far apart for too long. We need to bring together the people building the technologies, the ones framing the problems, and the ones directly impacted by the outcomes.

In the world of GeoAI, that’s especially important. No single entity — not a startup, not a university, not a government agency — can solve these challenges alone. The data is too complex, the stakes are too high, and the solutions require more than just technical talent.

An emerging example is the Taylor Geospatial Engine’s global field boundaries initiative. This goes beyond developing better models for agriculture. It’s about bringing data scientists, AI engineers, satellite imagery experts, and actual end-users – like farmers, NGOs, and governments – to the same table. When that happens, we don’t just build tools. We build systems that work in the real world.

This is the future – public-private-academic partnerships where the roles aren’t fixed and everyone has a voice. Researchers who listen to policymakers. Technologists who understand regulations. Community leaders at the design table, not just in the user testing phase.

So when I talk about collaboration, I mean co-creation. I mean shifting from a pipeline model – where someone “develops” and someone else “uses” – to a circular model where innovation flows both ways. That’s how we make sure GeoAI serves everyone, not just the technically privileged. And that’s how we move faster, with more purpose, and far greater impact.

What’s your message to the geospatial community as we navigate this shift, and what do we need to do next?

My message is simple: don’t play it safe. We are at a turning point. The convergence of satellite technology, AI, cloud computing, and open data has created a once-in-a-generation opportunity. But opportunity means responsibility, and this community has both. The decisions we make now – the tools we adopt, the partnerships we form, the infrastructure we build – will determine whether we lead or follow.

That means doing the right things, not just the exciting things.

- We need to build shared infrastructure and open tools – from simple schemas to cloud-native platforms to accessible foundation models.

- We need to make computing power and high-quality training data available to more people, because the cost of building advanced AI can’t become a barrier to open science or trust.

- We need to invest in training and upskilling – equipping people across sectors with the knowledge and confidence to use these tools effectively and responsibly.

- And we need shared benchmarks, so we’re not just moving fast, but measuring what works.

- But above all, we need to work together. No single player can solve the challenges we face. This is our moment to lead with purpose, to design systems that serve both people and planet.

Let’s not just map change. Let’s drive it. Together.

Be the first to comment