Summerside’s city council has voted against a proposed bylaw change that would have designated parts of the community as flood plain and coastal overlay zones. The decision followed a well-attended council meeting that drew about 80 residents who came to voice questions about what the proposed changes would mean for their homes and long-term planning. Summerside ultimately chose not to move forward, noting that the bylaw was linked to a non-mandatory requirement under the federal Housing Accelerator Fund and that concerns from both residents and council needed more time and clarity.

This story is more than a local decision. Across Canada, updated flood risk maps are becoming a common point of discussion as governments respond to changing climate conditions and new hazard data. Summerside’s experience illustrates the broader conversation happening in many municipalities about how flood mapping works, how it affects communities, and what role technology plays in informing risk.

Summerside Within a National Pattern

Summerside is not alone in navigating public concern linked to flood mapping proposals. Several municipalities across Canada have experienced similar conversations.

In Quebec, the province is currently rolling out a new flood zone classification system that will expand the number of properties designated as at risk. Municipalities across the province have raised concerns about how these classifications could influence property values and new construction, prompting the government to revise and consult further (Global News). Earlier, in Gatineau, large neighbourhoods were placed under new restrictions after the 2017 and 2019 floods, and many residents questioned the accuracy and impact of the mapping (Global News).

In New Brunswick, Saint John asked for additional clarity from the province before applying new coastal flood risk maps to municipal planning, citing the potential influence on redevelopment and property decisions (CBC New Brunswick). In the nearby Tantramar region, residents expressed concern that new maps were based on projections that felt too broad for local decision-making, and the municipality requested more refinement before adoption (CBC New Brunswick).

In Ontario, communities in the Muskoka region raised questions about updated floodplain boundaries that emerged after repeated spring flooding. Concerns centered on development restrictions and the cost of adapting to new requirements (CBC Ontario). Alberta has faced similar debates. After the 2013 floods, Calgary’s updated hazard maps triggered significant public concern, which led the province to pause and revise the maps before further consultation (CBC Calgary).

In British Columbia, several communities in the Fraser Valley have sought clearer detail after new post-2021 risk assessments expanded areas considered vulnerable. While not outright rejections, the discussions reflect the same underlying tension between hazard data and everyday implications for residents (CBC British Columbia).

These cases show that Summerside’s experience fits within a broader national trend. Municipalities are increasingly being asked to interpret technical datasets and climate projections in ways that support safety and long-term planning while also responding to community questions about economic and personal impact.

How Flood Mapping Works and Why Precision Matters

Flood mapping draws from several geospatial and climate datasets. Elevation models derived from LiDAR, digital terrain models, storm surge projections, historical water levels, and future sea level rise scenarios all contribute to the final maps. These maps provide an important planning tool for municipalities that need to prepare for long-term risks.

While these tools are powerful, they also present challenges. Some datasets are generalized at broader scales before municipalities translate them to the parcel level. Elevation differences of even a few centimeters can determine whether a home falls inside or outside a designated zone. Many provinces are now using future climate scenarios in their mapping, which increases long-term accuracy but can be difficult for the public to interpret because the projections cover several decades.

These precision questions are not unique to Summerside. They are part of the broader national discussion about how geospatial tools are used in planning.

Why Flood-Risk Mapping Is Growing Nationwide

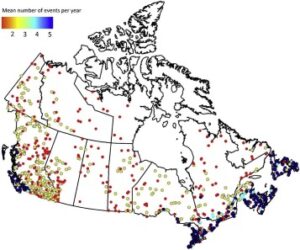

Canada is seeing more frequent and intense flooding events in several regions. Atlantic Canada faces some of the country’s fastest rates of sea level rise. Riverine flooding continues to affect communities in the Prairies, Ontario, and Quebec. In British Columbia, both atmospheric rivers and coastal flooding are reshaping long-term planning decisions.

Because of these changes, provinces and the federal government have been updating hazard data and encouraging municipalities to review or modernize zoning that relates to flood risk. The pace and scale of these updates vary across the country, but the trend is consistent.

The Root of the Tension

The recurring challenge across Canada is finding the balance between scientific data, municipal planning goals, and the concerns of residents. Flood maps are technical tools, yet they influence daily life. A designation can affect a mortgage application, insurance eligibility, or the value of a family home. At the same time, climate projections show clear shifts in flood behavior, which increases the pressure on governments to prepare for future conditions.

Many of the debates arise not from disagreement over whether risk exists, but from questions about how precise the mapping is, how it is communicated, and how the proposed regulations align with local realities.

What This Means for Future Planning

Canada’s climate and flood landscape will continue to change. Mapping technologies will become more detailed, and municipalities will continue to assess how to use these tools responsibly. Summerside’s decision highlights how complex the process can be. It also illustrates the importance of clear communication, strong technical foundations, and shared responsibility across government levels.

As more communities update their flood-risk mapping, the conversation about technology, planning, and public understanding will continue to evolve. Summerside’s experience shows that these decisions are not just technical exercises. They sit at the intersection of data, climate, and the lives of the people who call these communities home.

Be the first to comment