Canada’s long-awaited defense policy update promises a long-overdue ramp-up in spending — reaching the NATO benchmark of 2% of GDP within a year. For a country that has historically lagged behind its allies in military investment, this is a significant pivot. Yet buried beneath the headlines about jets, submarines, and cyber defense lies a critical omission: Canada’s geospatial infrastructure remains fragmented, dependent, and dangerously overlooked.

In a world where location data underpins nearly every military, economic, and civil system, the absence of a clear sovereign geospatial strategy is a vulnerability.

The Invisible Backbone of Modern Defense

Defense operations today — from targeting and surveillance to logistics and humanitarian relief — rely heavily on geospatial intelligence. This includes:

- Navigation systems (GNSS)

- Earth Observation for monitoring terrain and climate

- Secure, real-time spatial data platforms

- Software ecosystems that interpret location-based information

- Storage infrastructure that protects sensitive geographic data

These are core strategic assets. Their value spans across all domains: land, air, sea, cyber, and space.

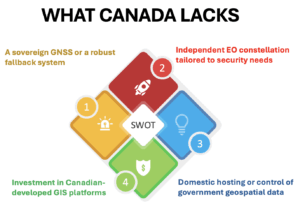

Yet, Canada lacks a unified vision to integrate, secure, or govern these systems. While the strategic importance of GEOINT is acknowledged in policy circles, the operational capacity to deliver on it remains limited. Infrastructure has not kept pace with intent.

Canada’s Strategic Blind Spot

Canada relies heavily on foreign GNSS systems (primarily U.S. GPS), licenses GIS software from foreign vendors, and outsources significant portions of its spatial data infrastructure. In many cases, critical national geospatial data — used for defense logistics, infrastructure planning, and emergency response — is processed or stored on foreign systems.

Canada’s dependence on foreign-owned platforms and cloud infrastructure raises serious sovereignty concerns. The U.S. CLOUD Act grants American authorities the power to access data held by U.S.-based companies, even when that data resides in other countries. As a result, sensitive Canadian geospatial information may be subject to foreign legal frameworks — with limited transparency or recourse.

In contrast, the European Union has long prioritized the development of sovereign data infrastructure. Countries such as France, Germany, the UK, India, and others are actively working to ensure that critical public-sector data is stored, processed, and governed within national or regional boundaries. These efforts go beyond cybersecurity, they are about preserving strategic autonomy. Without similar action, Canada risks ceding both control and influence over some of its most vital systems.

Even within the federal government, fragmentation persists. Agencies use different systems, standards, and platforms with little coordination. As a panel of high-level experts emphasized at GeoIgnite 2025, Canada lacks an overarching doctrine for how GEOINT should be integrated into national defense or civil operations. The result is a fractured landscape — technically competent, yet strategically misaligned.

A Decentralized GEOINT Framework

Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT) plays a vital role across defense, national security, and public service operations. In Canada, various federal departments and agencies are engaged in the collection, analysis, and use of spatial data for strategic purposes. However, the current GEOINT framework remains decentralized — a structure that allows flexibility but lacks overarching governance and coordinated national direction.

This concern continues to surface in policy and professional forums. It was a recurring theme at GeoIgnite 2025, and will also be addressed during a high-level panel at the upcoming Canadian Intelligence Conference (CANIC 2025), hosted by the Canadian Military Intelligence Association on June 17. The panel poses an important question: Is there a need for a dedicated Canadian Geospatial Intelligence Agency?

These limitations are particularly concerning in the context of NORAD modernization and Canada’s evolving role in continental defense. Shared early-warning systems, space-based surveillance, and Arctic domain awareness require precise, secure, and interoperable geospatial capabilities.

As the United States accelerates investments in next-generation missile warning, space tracking, and joint all-domain command systems, Canada’s lack of sovereign geospatial infrastructure creates a strategic constraint — limiting its ability to act as an equal partner.

The Arctic: A Case Study in Strategic Exposure

This vulnerability is especially pronounced in the Arctic., which illustrates the stakes of geospatial dependence — where terrain, sovereignty, and surveillance converge. It is a test case for Canada’s ability to act independently in contested space.

As polar routes open and resource competition intensifies, the region has become a geopolitical flashpoint. Russia continues to expand its Arctic military installations. China, branding itself a “near-Arctic state,” has invested in polar satellite systems, scientific bases, and submarine infrastructure. Both countries understand that mapping the terrain is a prerequisite to asserting influence.

Canada, by contrast, struggles to monitor its vast northern frontier in real time. Lack of sovereign Arctic-focused satellite systems and reliance on U.S. navigation data expose significant gaps. If relations with the U.S. were to deteriorate — as they increasingly show signs of strain — Canada would find itself without the sovereign tools needed to assert presence or respond independently in its own backyard.

Sovereignty Begins with Infrastructure

Geospatial sovereignty involves more than data access. It encompasses trust, resilience, and decision-making. Who controls the platform? Who sees the data first? Who determines the coordinate systems used in national security, infrastructure planning, or disaster response?

A serious response would include:

- Embedding geospatial infrastructure planning within the national defense architecture

- Establishing a national GEOINT strategy and governance framework to unify currently fragmented efforts

- Developing secure, Canadian-owned GIS platforms for public sector and military operations

- Expanding Canada’s EO capabilities for defense and civilian use

- Launching a Canadian GNSS initiative focused on Arctic resilience and redundancy

Multi-domain operations — from space to cyber to underwater surveillance — depend on location intelligence. Without control over the systems that collect, process, and store this intelligence, Canada’s contributions to allied missions and domestic readiness remain limited.

An Opportunity to Catch Up

The 2% defense commitment presents an unprecedented opportunity. With deliberate investment in sovereign digital infrastructure, including geospatial systems, Canada can build lasting security foundations.

Speaker after speaker at GeoIgnite emphasized that the challenge is not a lack of technical expertise or private sector capacity. What’s missing is political resolve and national coordination. Canada has the tools; it must now assemble them with purpose.

Strategic autonomy requires a clear vision and dedicated infrastructure. In an era of contested data, space militarization, and shifting alliances, Canada’s geospatial gap exposes national vulnerabilities.

Defense doesn’t begin at the border. It begins with a strategic data infrastructure — one we can call our own.

Be the first to comment