“I’ve got to get this right.”

It is a thought that surfaces again and again in geospatial work. A surveyor checks a control point one more time. A hydrographer reviews depth measurements knowing a small error can ripple outward. A navigator trusts coordinates that must align precisely with reality. In positioning, accuracy is not an abstract ideal. It is a requirement. Small errors compound, and precision is what holds the entire system together.

That insistence on getting it right guided the work of Dr. Gladys West, long before GPS became a technology most people could name. Working with early satellite data and limited computing power, West was part of the quiet mathematical effort to make global positioning reliable. Her work lived at the foundational level of positioning science, where small inaccuracies could distort satellite orbits, misrepresent the Earth, and undermine the very idea of knowing where something is.

Positioning Is Not Simple

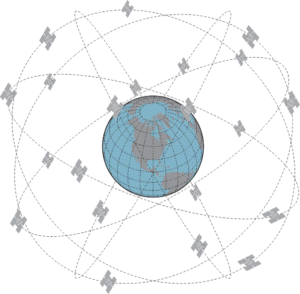

Modern GPS can feel effortless. A phone displays a location in seconds, often without a second thought about how that position was calculated. But positioning from space is one of the most complex scientific challenges solved in the twentieth century.

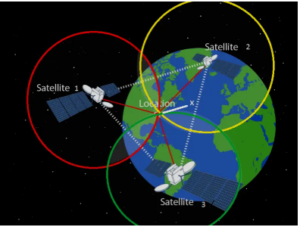

At its core, positioning requires knowing where satellites are, measuring distances through precise timing, and translating those measurements into coordinates on the Earth. Each step demands accuracy. A slight error in satellite orbit calculations affects distance estimates. Small timing inaccuracies translate into large positional shifts on the ground. None of this works unless there is a stable mathematical relationship between satellites and the planet beneath them.

This is where positioning stops being just a technology problem and becomes a geometry and Earth science problem.

The Shape of the Earth Complicates Everything

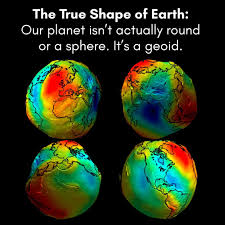

Satellite-based positioning depends on precise geometry, timing, and orbit determinationThe Earth is not a perfect sphere. It is not even a smooth ellipsoid. Gravity varies across the planet due to uneven mass distribution, oceans, mountains, and the dynamic nature of the Earth itself. These variations distort the surface into an irregular shape known as the geoid, an invisible reference surface defined by gravity rather than topography.

For positioning systems, this matters deeply. Heights, satellite trajectories, and ground coordinates all depend on how the Earth is modeled. Approximations can only go so far. To determine position accurately at a global scale, scientists had to be precise, careful, and exacting about how the Earth’s shape was represented.

As West later put it, “You had to be particular.”

That particularity was not optional. It was imposed by the planet itself. Modeling the Earth required accounting for subtle variations that early satellite data only began to reveal. The work demanded patience, repetition, and a willingness to refine models again and again as better measurements became available.

The Work Beneath Position

Gladys West’s career unfolded at the intersection of satellite motion and Earth modeling, where positioning science is built. At the U.S. Naval Surface Warfare Center, she worked on analyzing satellite data, refining orbit calculations, and contributing to mathematical models of the Earth derived from those observations. This included work related to gravity-informed Earth models and geoid calculations, which are essential for translating satellite measurements into reliable positions on the ground.

Her work was computationally demanding. Using early mainframe computers, West programmed and processed large datasets at a time when computing resources were limited and errors were costly. Small mistakes could propagate through calculations, affecting orbit predictions and Earth models alike. Precision was not just encouraged. It was necessary.

Much of this work took place decades before GPS became publicly available, as part of a broader effort to understand satellite behavior and the Earth itself. The positioning systems that later emerged relied on this groundwork. It was built on layers of careful mathematical and geodetic work, much of it unseen.

West did not seek attention for that role. “I didn’t brag about what I was working on,” she once said. But the impact of that work is now embedded in every coordinate we trust, every navigation route we follow, and every map that assumes the Earth can be measured accurately from space.

Before GPS Became Public, the Math Had to Be Right

The positioning accuracy we rely on today did not emerge overnight. Long before GPS entered civilian use, the underlying mathematics, satellite tracking, and Earth models had to be tested, refined, and trusted. This work unfolded over years, often without a clear sense of how widely it would eventually be used.

West later reflected on this disconnect between effort and visibility, noting, “You never think that anything you are doing militarily is going to be that exciting.” At the time, her work focused on solving immediate technical problems: processing satellite data reliably, modeling motion and gravity accurately, and reducing error in systems where small inaccuracies could cascade. The broader implications only became clear later, when positioning systems moved beyond military and research contexts into everyday life.

This pattern was not unique to West. The space age relied on mathematicians whose work rarely appeared in headlines but whose calculations carried enormous consequences. Figures like Katherine Johnson are now widely recognized for trajectory and orbital calculations that ensured spacecraft could navigate space safely and return to Earth. While Johnson’s work focused on charting paths through space, West’s work addressed a different but equally fundamental challenge: defining position accurately on the Earth itself using satellites.

Together, their careers illustrate the dual nature of satellite navigation: ensuring objects move correctly through space, and translating those movements into meaningful positions on the ground. Both depend on mathematical precision. Both demand discipline. And both require an understanding that errors, however small, can have far-reaching effects.

For West, this meant returning again and again to the fundamentals of Earth modeling and satellite data processing. The Earth’s irregular shape, influenced by gravity and mass distribution, did not allow for shortcuts. Being “particular” was not a matter of preference but a response to the physical reality of the planet. The accuracy of future positioning systems depended on it.

By the time GPS became publicly accessible, much of this foundational work had already been done. The technology appeared seamless to users, but it rested on decades of careful calculation and verification. The precision demanded in those early years became embedded in the systems that now quietly guide navigation, mapping, and measurement across the globe.

What We Build On

Today’s geospatial tools rest on an assumption that position can be trusted. Coordinates align across datasets. Heights are referenced consistently. Satellite imagery lands where it should. For most users, this reliability fades into the background, noticed only when something goes wrong.

But that trust is earned, not automatic.

The positioning accuracy that underpins GNSS, surveying, hydrography, GIS, and remote sensing depends on the same foundational work West contributed to decades earlier. Satellite orbits must be known precisely. Earth models must account for gravity-driven irregularities. Reference surfaces must be stable enough to support everything built on top of them.

In practice, this means that a survey measurement ties back to global reference frameworks. A marine chart depends on accurate vertical relationships between sea surface, seafloor, and satellite-derived heights. A remote sensing image relies on geolocation models that assume the Earth’s shape has been carefully defined. Each of these workflows inherits the discipline embedded in early positioning science.

West understood that discipline well. That insistence on exactness was not a personal preference but a response to the nature of the problem. When modeling the Earth and satellites together, there is little tolerance for approximation. Precision at the foundational level determines reliability across the entire system.

Her work remains largely invisible because it succeeded. When positioning works, it disappears. Coordinates line up. Systems agree. Users move on. Yet beneath that ease is a structure built from careful calculation, repetition, and restraint, the kind of work that rarely announces itself.

For the geospatial community, this legacy is familiar even if her name was not always attached to it. The expectation that position should be consistent, transferable, and accurate across space and time reflects the standards she worked under. It is the same expectation that continues to guide professional practice today.

Precision Before Recognition

Gladys West never framed her work as historic. She approached it as a problem that demanded care. Calculations had to be checked. Models had to be refined. Results had to be right. The consequences of error were not abstract, even if the applications were still emerging.

That mindset, more than any title or later recognition, defines her legacy. In positioning science, precision comes before visibility. Accuracy comes before convenience and trust is built long before it is noticed. West understood this instinctively, working in a field where success often meant that nothing appeared to go wrong.

Only later did the significance of that work become widely understood. As GPS moved from military and research contexts into civilian life, the foundations she helped build quietly expanded their reach. Today, global positioning supports navigation, mapping, environmental monitoring, emergency response, and scientific research across the planet. Each application assumes that position can be defined consistently and reliably, an assumption rooted in decades of careful mathematical and geodetic work.

Her passing is a moment to look beneath the tools we use every day and remember the science that makes them dependable. Positioning is not magic. It is the result of discipline, patience, and an insistence on getting things right, even when the work remains unseen.

For generations of geospatial professionals, that instinct remains familiar. The quiet pause before accepting a result. The extra check. The refusal to round away uncertainty. In that shared ethic of precision, Gladys West is still present, embedded in the systems that continue to define where we are.

Be the first to comment