From Hydrographic to Hydrospatial

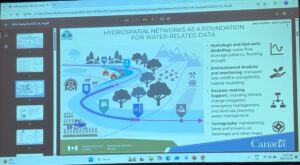

Fuss opened with an important distinction: “hydrospatial” goes beyond traditional hydrographic datasets. While hydrographic networks focus primarily on charting and navigation, the hydrospatial framework represents a richer, interconnected system that includes rivers, lakes, wetlands, flow paths, and catchments — all linked in a seamless geospatial network. This model provides the infrastructure to support everything from flood modeling and wildfire risk assessment to climate change mitigation and water quality monitoring.

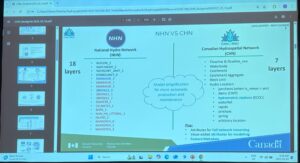

The goal of the CHN is to replace older datasets like the National Hydro Network (NHN) with a more usable, accurate, and scalable system. The CHN boasts simplified data layers, higher spatial resolution, improved update frequency, and greater interoperability with international models — especially the 3DHP (3D Hydrography Program) in the United States.

Engineering a Modern Water Network

Colleen walked us through the CHN’s production workflow, which leverages the best of both automation and manual validation. The team uses high-resolution Lidar-derived elevation models, AI-driven surface water detection, and in-house pruning algorithms to ensure accurate flow lines, even beneath forest canopies. Manual correction remains a key part of the process, especially in challenging areas like wetlands and headwaters, where automated tools alone aren’t sufficient.

The network is structured to include:

- Flow lines and water bodies

- Catchments and aggregated work units

- Hydrometric stations (e.g., Environment and Climate Change Canada gauges)

- Network traversing logic and rich metadata for each element

This meticulous design enables advanced modeling capabilities, such as watershed flow routing, pollutant tracking, flood risk analysis, and habitat modeling — all critical functions for researchers, governments, and infrastructure planners.

Built for Interoperability and Insight

A highlight of the CHN is its adherence to the OGC Hydro Features standard, which ensures compatibility with other modern hydrologic models. Colleen emphasized ongoing collaboration with USGS teams to align CHN with U.S. standards, facilitating cross-border hydrologic analysis – a crucial capability for managing shared watersheds.

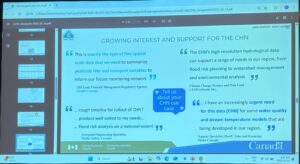

She also showcased how CHN data is already being used:

- Health Canada is exploring pesticide transport modeling

- Public Safety Canada is applying it to flood risk forecasting

- Watershed managers are using it for land-use and infrastructure planning

The CHN’s open data delivery model, including web services, downloadable datasets, and graph database formats, ensures broad accessibility and encourages innovation. Colleen also encouraged attendees to contribute ideas and use cases, reinforcing the CHN’s role as a collaborative platform, not just a government dataset.

A Broader Vision for Canada’s Hydrospatial Future

The best part about Fuss’s presentation was how it framed the CHN as a living system — one that evolves based on user feedback, R&D advances, and new environmental challenges. With national coverage planned by 2028, the CHN will soon become the default reference for surface water in Canada, supporting applications from local flood planning to national climate resilience modeling.

Her emphasis on partnerships with provinces, Indigenous communities, and the research sector also shows a strong commitment to equity and inclusivity in how hydrospatial infrastructure is built and shared.

In an era where water-related risks are rising and environmental modeling is becoming more data-driven, the CHN is a timely and transformative initiative. Colleen’s leadership and the collaborative effort behind this network make it clear: Canada is not just mapping its waters — it’s reimagining them as intelligent, connected systems.

Be the first to comment