Dan Campbell is an urban planner at the City of Vancouver. I’ve seen and heard several of Dan’s presentation over the past few years in Singapore, Bellevue, and other places and I always look forward to them, because they always have an intriguing slant while being practical at the same time.

This year at Autodesk University, Dan makes the case that for a city, while 3D would be nice, in practice there are advantages in using an approximation that Dan calls 2.5D.

Vancouver has 170,493 buildings. As a rough calculation Dan assumed that if he spent something on the order of 20 minutes modeling each building, which seems a pretty low estimate, he would need 29 years to model Vancouver in 3D, and that doesn’t include all the infrastructure outside of the buildings. This is tongue in cheek, of course, but Dan’s point is that we need a faster way to create a city model using existing 2D data.

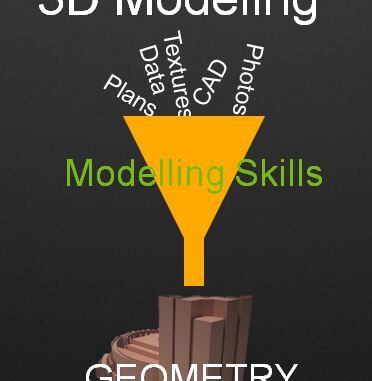

In traditional 3D modeling, source data such as architectural drawings, photographs, point clouds, and GIS data are used to create the model. For the most part, once the model is completed, the source data is discarded leaving only the very complex 3D model geometry. And the modeling skills that are required to create the model are significant.

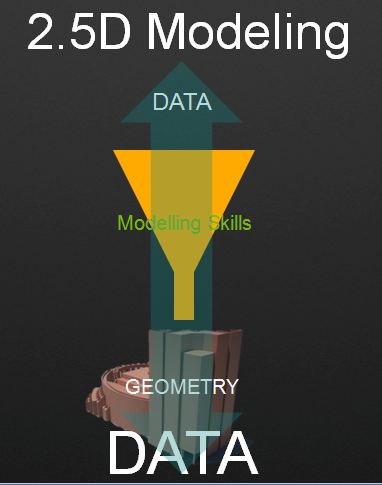

The difference in working with 2.5D data is all the attributes required to create the model can stay with the model. This means there is 3D geometry, but the model has intelligence as well. With the 2.5D approach the model geometry will be much simpler than that generated through full 3D modeling. 2D building footprints are extruded using building heights or number of floors to form a simple geometry. Not only is the model simple to create and visualize, but the modeling skills required are much less.

The difference in working with 2.5D data is all the attributes required to create the model can stay with the model. This means there is 3D geometry, but the model has intelligence as well. With the 2.5D approach the model geometry will be much simpler than that generated through full 3D modeling. 2D building footprints are extruded using building heights or number of floors to form a simple geometry. Not only is the model simple to create and visualize, but the modeling skills required are much less.

Not Seeing the Forest For the Trees

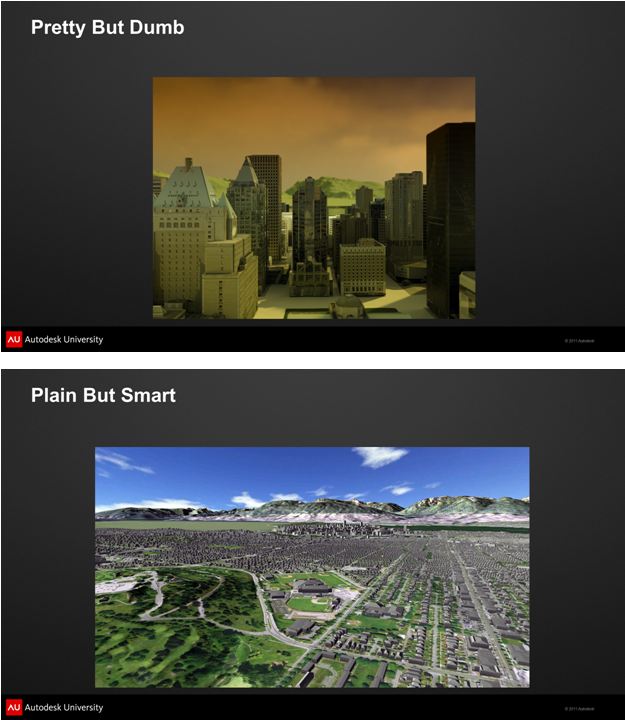

To properly address all the issues facing cities, it is important to be able to see the big picture. Because of software and hardware limitations, this hasn’t really been possible until recently. From Dan’s perspective, Autodesk Infrastructure Modeler has allowed the City, for the first time, to work at the full extents of the City of Vancouver. Although the model is visually less rich at this scale, it is a more than acceptable trade-off for all the other benefits. As well, visual fidelity is not always necessary, and being able to view data in a more abstract manner can be more appropriate for certain tasks. In other words, a full 3D model is often pretty, but not very useful because the trees get in the way of the forest, whereas a 2.5D approximation might be plain, but it makes it easier for the urban planner to use the model to get useful results about the forest.

To properly address all the issues facing cities, it is important to be able to see the big picture. Because of software and hardware limitations, this hasn’t really been possible until recently. From Dan’s perspective, Autodesk Infrastructure Modeler has allowed the City, for the first time, to work at the full extents of the City of Vancouver. Although the model is visually less rich at this scale, it is a more than acceptable trade-off for all the other benefits. As well, visual fidelity is not always necessary, and being able to view data in a more abstract manner can be more appropriate for certain tasks. In other words, a full 3D model is often pretty, but not very useful because the trees get in the way of the forest, whereas a 2.5D approximation might be plain, but it makes it easier for the urban planner to use the model to get useful results about the forest.

Be the first to comment