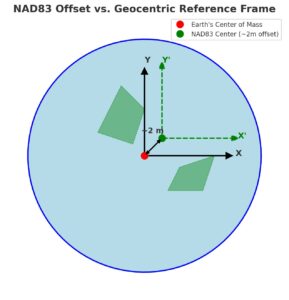

North America is undergoing a significant shift in how geographical positions are defined. Both Canada and the United States are moving away from NAD83 (North American Datum of 1983), a system introduced in the 1980s that is now misaligned by about two metres from the Earth’s true center of mass. The transition is to a new geocentric framework aligned with the International Terrestrial Reference Frame. Both Canada and the United States are adopting this as NATRF2022. In Canada, it is part of the broader modernization of the Canadian Spatial Reference System (CSRS), while in the U.S. it is being implemented through the modernization of the National Spatial Reference System (NSRS). The coordinated efforts ensure compatibility across the border and beyond.

To understand what this shift means in practice, we spoke with Brian Donahue, lead of the Client Services team at the Canadian Geodetic Survey, chair of the Canadian Geodetic Reference Systems Committee (CGRSC), and a key figure in delivering CSRS modernization. We also spoke to industry professionals such as Eric Wilson (EcoDraft Solutions) and others who shared their perspectives on how this transition will affect work in the field.

Why Canada is Modernizing

When NAD83 was introduced in the 1980s, space-based measurement techniques like GPS were still new. The system was intended to be geocentric but fell about two meters short. That gap shows up today as a one- to two-metre difference between GPS positions and NAD83 coordinates, a headache for anyone working in high-precision applications.

Modern technologies, from autonomous navigation to precision agriculture, rely on real-time satellite positioning. Expecting every user to understand and apply transformations between NAD83 and GPS is no longer realistic. The modernization aims to simplify this: Canada’s new geocentric reference will be naturally aligned with GPS and other GNSS, eliminating the hidden complexity.

Another driver is cross-border compatibility. The United States is preparing to adopt the NATRF2022 as well, on a similar timeline. By modernizing CSRS in step with the U.S., Canada ensures that projects and data spanning the border, from water management to infrastructure planning, will line up seamlessly.

The 25-Year Journey of CSRS Modernization

Canada’s geodetic system has been evolving for more than a generation. Each stage has reflected both the limits of the time and the opportunities created by new technology.

In the late 1990s, NAD83 was extended into NAD83(CSRS). For the first time, Canada had a three-dimensional version of its reference frame that could keep pace with GPS. It was an essential first step, connecting ground surveys with signals coming from space.

The next leap came around 2006, when the Canadian Geodetic Survey introduced a national model of crustal motion. Across Canada, the land is constantly shifting, the North American plate moves, big earthquakes shake the West coast, and most of Canada still rebounds from the weight of ancient ice sheets. The new model allowed surveyors and scientists to stitch together datasets collected at different times and still trust their alignment.

By 2015, attention turned to heights. The century-old leveling system known as CGVD28 gave way to CGVD2013, a vertical datum tied to gravity itself. This change provided a consistent way to measure elevation across the country, free from the distortions that had built up over decades of leveling surveys.

The next stage is now within reach. The Canadian Geodetic Survey plans to adopt a truly geocentric reference frame in 2026, bringing the system into line with the Earth’s center of mass. Provinces and territories, through the Canadian Geodetic Reference Systems Committee (CGRSC), are preparing for unified adoption by 2030. Seen together, these milestones tell a story of steady modernization, one that has carried Canada from the early days of adapting NAD83 to a future anchored firmly in the geometry of the Earth itself.

Timeline and Governance

The modernization is moving on two tracks: federal adoption and provincial alignment.

At the federal level, the Canadian Geodetic Survey has set 2026 as the year it will adopt the new geocentric frame. That decision will define the system used by federal agencies and national datasets.

For the provinces and territories, the path is more complex. Each jurisdiction has the authority to decide which reference frame it will use. Some are still tied to older realizations of NAD83(CSRS), while others have already updated. The goal now is to bring everyone together. Through the Canadian Geodetic Reference Systems Committee (CGRSC), federal and provincial partners are working toward a unified adoption by 2030.

This phased approach reflects both practical realities and limited resources. NAD83(CSRS) will remain available for years to come, giving surveyors, GIS professionals, and municipalities the time they need to adapt. The push toward 2030 is as much about creating national consistency as it is about modernization itself.

What Users Will See

For most professionals, the shift to a geocentric frame will show up as a horizontal offset of about one to two metres when comparing coordinates between NAD83(CSRS) and the modernized CSRS. As Brian Donahue of the Canadian Geodetic Survey explained, “The big thing is a horizontal shift of about one to two metres when comparing data sets.”

That shift doesn’t mean surveyors will need to remeasure every parcel or project. A mathematical transformation is already defined, and it will allow coordinates in NAD83(CSRS) to be migrated into the modernized system. What really matters is the quality of metadata. If datasets are carefully documented, with the right reference frame, epoch, and projection, the migration can be automated within software. Without that information, the process becomes guesswork.

Industry Voices: Perspectives from the Field

Not everyone in the geospatial community is moving at the same pace toward adoption. Some professionals anticipate a transition period where NAD83 and the new systems will coexist, creating a mixed landscape for firms and agencies.

Eric Wilson, owner of EcoDraft Solutions, highlighted the communication challenges that lie ahead: “Navigating this transition will likely present a significant communication challenge. Not all firms will immediately adopt the new standard, with many opting to continue using NAD83 for the foreseeable future. The industry will likely wait to see what others are doing before committing to the change themselves. Firms that do transition will need to clearly communicate this when sharing data with clients, colleagues, and other organizations. Failing to do so could lead to considerable confusion and errors.”

Others pointed out sector-specific concerns. In the mining industry, for instance, questions have been raised about how legacy survey data will align with future datasets. With resource projects often stretching over decades, even a one- to two-metre positional shift could ripple through land records, engineering plans, and legal boundaries.

The Canadian Geodetic Survey is well aware of these concerns. Donahue emphasized that no one will be left behind in the transition. “Having correct metadata is what really allows users to migrate existing NAD83 datasets to NATRF2022. Without complete and accurate metadata these migrations are not really possible.”

To ease the shift, CGS is working with major software providers such as Esri, Trimble, and Autodesk, ensuring that datum transformations can eventually be handled directly within the tools professionals use every day. The aim is a future where much of the complexity happens behind the scenes, allowing practitioners to focus on their work rather than geodetic conversions.

By coordinating with provincial survey associations, software developers, and the broader geospatial community, CGS aims to ensure that modernization does not simply happen to users, but with them.

Canada in the Global Geodetic Community

Modernizing Canada’s Spatial Reference System is not only about national needs. It is part of a larger story in which geodesy has become a global effort. Precise positioning depends on a worldwide network of satellites and ground infrastructure, and no single country can sustain that system on its own.

As Donahue put it, “Geodesy is a global effort now. No one country can deliver a precise reference system on their own.” To build a stable reference frame for North America, geodesists first rely on the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF). This global foundation is made possible through international collaboration, with permanent GNSS stations, observatories, and other monitoring systems spread across continents. Canada benefits from this global infrastructure, and in turn, has a responsibility to contribute.

One area where Canada sees opportunity is in strengthening its role in the Global Geodetic Observing System (GGOS). Today, Canada operates a strong GNSS network, but it does not yet host the full suite of space-geodetic techniques, such as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) or Satellite Laser Ranging (SLR). Expanding into these areas would increase Canada’s ability to monitor Earth’s dynamics and ensure that its reference system remains accurate into the future.

In this way, the modernization of CSRS is both an outcome of global cooperation and a step toward deeper participation. By aligning with international standards and contributing more actively to global observing systems, Canada positions itself not only as a beneficiary of geodesy’s progress but also as a partner shaping its future.

Looking Ahead

Canada’s modernization of the CSRS marks the culmination of decades of incremental progress and the start of a new chapter in positioning. The changes will be most visible to surveyors, GIS professionals, and those working in industries where precision is critical. For others, the shift may feel gradual, guided by software updates, professional standards, and communication efforts already underway.

What stands out most is the collaborative nature of this effort. From the Canadian Geodetic Survey to provincial agencies, surveyor associations, geospatial firms, and even software providers, modernization depends on shared responsibility. Internationally, alignment with the United States and integration into the global geodetic community ensure that Canada’s positioning infrastructure remains relevant in a world where location underpins everything from navigation to resource management.

In the end, the modernization of the CSRS is not only about coordinates shifting by a metre or two. It is about ensuring that Canada has the foundation to support emerging technologies, global collaboration, and the everyday reliance on accurate location that society now takes for granted.

Be the first to comment