A new GoGeomatics survey on the State of Geomatics Education and Workforce Development in Canada reveals a sector deeply worried about the health of its education pipeline. With several college and university geomatics programs already closed or at risk of closing, respondents warn that Canada may soon face a serious shortage of qualified professionals just as national infrastructure spending reaches historic levels.

The survey — which gathered 270 responses from across the geomatics and geospatial community, spanning public-sector professionals (57%), private-sector leaders (36%), and voices from academia, management, and the next generation of students — shows a strong consensus that the education system is struggling to keep pace, governments are out of touch with industry needs, and outdated job classifications are holding back workforce planning and investment.

Education not keeping pace with national needs

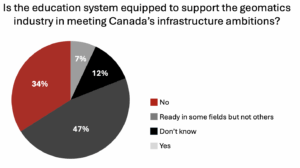

Asked whether Canada’s education system (Q5) is equipped to support the geomatics and geospatial industry amid major infrastructure investments, a significant number (34%) said “no,” while nearly half (47%) said it is “ready in some fields but not others,” suggesting uneven preparedness across disciplines.

Only 7% of respondents felt the system is well equipped. It was a clear sign that, despite growing national investment in infrastructure, the talent pipeline remains fragile.

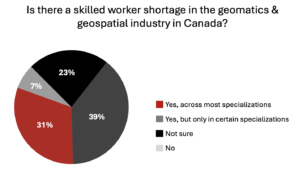

This concern is reflected in broader workforce trends. When asked whether Canada faces a skilled worker shortage in the geomatics and geospatial industry (Q6), 71% agreed (31% reported shortages across most specializations and 39% saying the gaps exist in specific fields). The shortfall is felt particularly in technical and field roles, where employers are struggling to attract qualified candidates.

Geomatics program closures a worrying issue

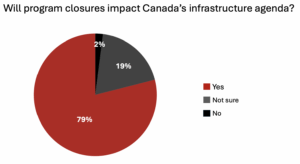

The survey also asked about the recent or potential closure of several college and university geomatics programs across Canada — and the response was overwhelming. Nearly 79% of participants believe these closures will directly impact Canada’s ability to deliver on its infrastructure agenda. (Q11)

This signals more than an academic concern; it’s a national issue that threatens Canada’s ability to sustain the technical workforce essential for surveying, mapping, and managing major infrastructure projects.

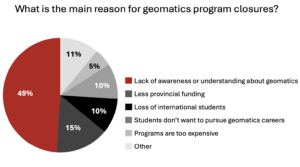

When asked why programs are closing, 49% pointed to a lack of awareness or understanding about geomatics itself, far surpassing other causes such as reduced funding (15%) or loss of international students (10%). (Q10)

Respondents were equally clear about what could help turn this around (Q14). Top suggestions included integrating geospatial education into K12 science curriculum (77%), building industry-education partnerships for internships and co-ops (66%), expanding career counselling in high schools (61%), and offering bridging programs for early/mid-career professionals (52%). (This question allowed multiple selections, so the percentages reflect the range of actions respondents support rather than adding up to 100%.)

The message is clear: the problem begins with visibility — and must be addressed long before students choose postsecondary paths. Interestingly, this message about lack of visibility and the need for enhanced focus on geo-literacy had also come up in the responses for the other parallel industry survey on procurement we were running.

Employers say new graduates need extensive training

These gaps in awareness and education feed directly into hiring and onboarding challenges faced by employers. When it comes to job readiness, respondents were again divided but critical. While 22% said new hires require only limited training, one-third (34%) said graduates need substantial additional preparation before they can contribute effectively. Another 32% said readiness “depends on the school they attended,” highlighting uneven standards across institutions. (Q15)

Only 5.8% of respondents felt graduates are ready to contribute immediately — a sign that employers continue to bear the burden of extensive onboarding and retraining.

Only 5.8% of respondents felt graduates are ready to contribute immediately — a sign that employers continue to bear the burden of extensive onboarding and retraining.

Respondents were asked which positions are the easiest to fill — a question that allowed multiple selections. The most frequently cited were geospatial/geomatics analysts (47%), sales roles (41%), and field crew positions (39%). Developers (31%) and management roles (29%) were also seen as comparatively easier to staff. (Q7)

At the other end of the spectrum, very few respondents identified digital twin experts (1.5%), geodesists (1.5%), remote sensing specialists (15%), AI/data scientists (18%), BIM/GIS interoperable roles (17%), or land surveyors (17%) — indicating that these specialized technical roles remain among the most difficult to fill across the sector.

(This question allowed multiple selections, so the percentages reflect the range of actions respondents support rather than adding up to 100%.)

Recruitment difficulties also differ by work type (Q9): 23% said it is harder to recruit for field positions than office-based ones, with another 23% saying it depends on the specialization. Employers cited both the technical skill demands and the physical realities of fieldwork as barriers to attracting younger professionals.

Governments out of touch with workforce and training realities

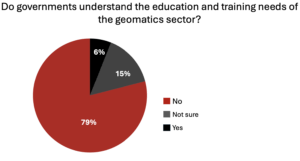

An equally striking finding: 79% of respondents believe federal and provincial governments do not understand the education and training needs of the geomatics and geospatial sector. (Q12) Only 6% felt confident that policymakers grasp the skills and competencies required to support Canada’s rapidly evolving digital infrastructure.

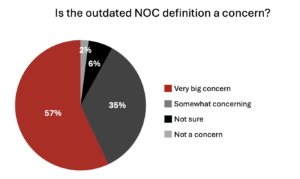

That gap in understanding extends to how government defines the geomatics profession itself. When it comes to the 30-year-old federal definition of geomatics and geospatial roles in the National Occupation Classification (NOC), the verdict was nearly unanimous: over 90% of respondents said the outdated framework is a concern, with 57% labelling it a “very big concern.” Q17

That gap in understanding extends to how government defines the geomatics profession itself. When it comes to the 30-year-old federal definition of geomatics and geospatial roles in the National Occupation Classification (NOC), the verdict was nearly unanimous: over 90% of respondents said the outdated framework is a concern, with 57% labelling it a “very big concern.” Q17 Respondents warned that an obsolete framework affects everything from labour mobility and immigration to program funding and workforce planning.

Respondents warned that an obsolete framework affects everything from labour mobility and immigration to program funding and workforce planning.

Strong call for regular consultation and coordinated reform

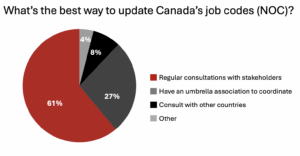

When asked how best to modernize Canada’s job codes and ensure they reflect emerging technologies and processes, a strong 61% favoured regular consultations with public and private stakeholders. Another 27% called for the creation of an umbrella geospatial association to coordinate such efforts. (Q18)

Not a single respondent supported the idea of letting the government “continue as it is.”

Many respondents also proposed clear priorities for aligning education and workforce systems with industry evolution. Top suggestions included expanding co-ops and work-integrated learning (73%), updating curricula to include AI, UAVs, and digital twins (65%), increasing collaboration between industry and academia (64%), and introducing geospatial literacy earlier in K–12 (54%). These ideas offer a practical roadmap for rebuilding Canada’s training ecosystem. (Q16)

Many respondents also proposed clear priorities for aligning education and workforce systems with industry evolution. Top suggestions included expanding co-ops and work-integrated learning (73%), updating curricula to include AI, UAVs, and digital twins (65%), increasing collaboration between industry and academia (64%), and introducing geospatial literacy earlier in K–12 (54%). These ideas offer a practical roadmap for rebuilding Canada’s training ecosystem. (Q16)

A sector ready to act — but waiting for leadership

Across the survey, one message stands out: Canada’s geomatics community is ready to adapt and collaborate — but leadership and coordination are urgently needed. Participants called for stronger ties between academia and industry, consistent standards, and recognition that geospatial education underpins every infrastructure project the country hopes to deliver in the coming decade.

These findings reinforce what GoGeomatics has been hearing in recent months through its interviews and coverage with senior academics and industry professionals — a shared concern that Canada’s geomatics education system is struggling to meet the scale of opportunity ahead. The survey brings quantitative weight to what many in the community have already voiced: the need for coordinated national action.

As Canada prepares for massive investments in housing, transportation, and climate resilience, the results send a clear warning: without modernized programs and a coherent workforce strategy, the country risks falling short of its ambitions.

(The findings will help inform discussions at the Canadian Geomatics & Geospatial Advisory Forum at GoGeomatics Expo 2025, where education leaders, employers, and policymakers will explore solutions to rebuild Canada’s geospatial talent pipeline.)

Be the first to comment