For decades, the U.S. has been a key player in Arctic monitoring. Its satellites support climate models, disaster response, and international cooperation. Now, there are signs that the U.S. may pull back. The 2026 NASA budget, released on May 2, proposes reduction over $1 billion from Earth science programs – that over 50% cut. It also suggests restructuring the Landsat Next program and eliminating “low-priority climate monitoring satellites.” NOAA, the agency focused on weather and climate research, could face a 27% funding cut, impacting ocean research, coastal management, and shifting critical satellite programs.

If the U.S. steps back, the question isn’t who will replace it — it’s who will step up.

And we are talking about only the Arctic here.

Canada is in the perfect position to lead Arctic monitoring. Yet, unlike Russia, which has dedicated Artic monitoring satellites like Arktika-M, and China, which is expanding its polar research, Canada has mostly relied on NASA’s infrastructure. We haven’t fully leveraged our own technology or ESA partnerships to address the rapidly changing environment of the North.

A Nation with Northern Responsibility

The Arctic is more than just a region – it’s a global warning sign. What happens there impacts the entire world. Ice is melting, permafrost is thawing, and ecosystems are shifting. As coastlines recede and ice melts, new sea routes open, and energy reserves become more accessible. Global powers are taking notice.

For Canada, monitoring the Arctic isn’t optional – it’s essential. Especially as Russia’s military buildup and nuclear-powered icebreakers assert control over the Northern Sea Route, and China, which now calls itself a “near-Arctic state,” ramps up its research and Earth observation (EO) programs as part of its Polar Silk Road initiative.

Canada needs real-time monitoring to track naval movements and protect territorial claims. Beyond defense, Canada’s Arctic strategy must leverage EO to manage resources, track environmental shifts, and safeguard ecosystems.

The Arctic is warming four times faster than the global average. Thawing permafrost, disappearing sea ice, and changing ecosystems are disrupting weather patterns. In 2023, Canada saw its worst wildfire season ever — 18.5 million hectares burned, six times the national average. In the North, melting permafrost causes infrastructure failure, food systems struggle, and evacuations become more frequent.

Strengths, Strategies, and Misfired Potential

Canada’s spending in Earth Observation infrastructure is modest. While exact investments in EO is not available for counties, a comparison of overall space budgets show a not too rosy picture. As a share of GDP, Canada’s space budget ranks 22nd among OECD nations. In contrast, countries like the United States, France, and Germany, as well as some smaller economies, allocate a much larger proportion of their GDP to space. This disparity underscores Canada’s competitive gap in space investments and highlights the broader ambitions of nations that dedicate more resources to advancing their space programs.

While our investment is modest, we are also not leveraging our advantages!

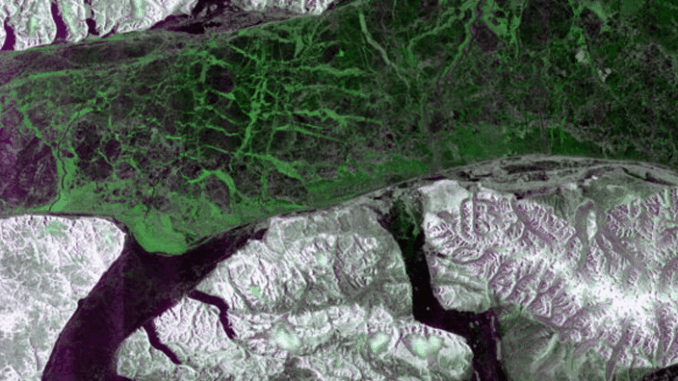

Canada has led the way in radar-based EO for nearly 30 years. RADARSAT-1, the world’s first commercial SAR satellite, was launched in 1995, by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) and MDA. This was followed by RADARSAT-2 and the RADARSAT Constellation Mission (RCM). In 2023, the federal government committed another $1 billion to RADARSAT+, to build the next-generation program.

But our EO toolkit is still limited. We have SCISAT for tracking greenhouse gases, and we’re launching WildFireSat and HAWC to monitor wildfires and extreme weather. But we need more.

Canada has also contributed to international missions like NASA’s CloudSat and ESA’s SMOS. Private companies like GHGSat and EarthDaily Analytics are making strides in climate-focused EO. The CSA has supported a growing EO ecosystem, but we still lack a coordinated national strategy.

In 2022, the government released its Strategy for Satellite Earth Observation, a blueprint meant to align EO with Canada’s climate, economic, and innovation goals. On paper, it was the direction the sector had been asking for. But since then, progress has been slow. There’s no formal structure to make it happen, no dedicated funding, and no public tracking of progress.

Ties That Should Be Stronger: Canada and ESA

Canada’s partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA) is a huge asset. As the only non-European country in ESA, we have access to some of the most advanced EO data and technologies. But this partnership hasn’t been fully tapped for Arctic monitoring and climate resilience.

In 2015, Canada joined ESA’s Sentinel Data Hub, setting up a national mirror site for faster access to Copernicus satellite imagery. In 2022, the Copernicus Arrangement was signed, enabling the reciprocal exchange of EO data with a focus on the Arctic. Yet, from 2015 to 2020, only 30% of Canadian space organizations participated in ESA activities. Many smaller companies and researchers don’t know how to bid on European projects.

Experts argue that Canada should increase its investment in ESA and better align the partnership with national priorities. Co-developing an Arctic weather satellite system or supporting next-gen climate missions could strengthen our leadership. The Arctic Observing Mission, currently being studied by the CSA, could attract international partners — including ESA members — to help co-develop Arctic climate data systems.

Arctic Leadership Isn’t Optional

Then there are opportunities to partner with other countries for Arctic monitoring. Japan is a strong candidate, with JAXA operating advanced technologies suited for ice, water, and permafrost monitoring. While not traditionally Arctic-focused, India is expanding its satellite capabilities. Recently, Canada and Australia partnered on a radar system for Arctic monitoring, leveraging Australia’s expertise in Antarctic surveillance to enhance long-range capabilities for monitoring the North.

The world needs reliable Arctic climate data, and Canada is in the best position to provide it. To lead, Canada must prioritize Arctic EO in every major space investment. This means:

- Building stronger data infrastructure and improving access for communities.

- Putting Indigenous science and local data needs at the center of EO strategy.

- Using ESA, NASA, and private-sector partnerships with purpose.

This isn’t about filling America’s shoes. It’s about standing firm in our own. We need to treat Arctic EO leadership as a national responsibility. Leadership doesn’t always come with scale. Sometimes, it comes from the North.

Be the first to comment