Canada’s geomatics and geospatial sector touches nearly every area of national interest — from infrastructure development and resource mapping to climate monitoring, emergency response, and public safety. It underpins smart cities, clean energy, transportation, and even Indigenous governance. Yet, despite its influence, the sector remains largely invisible in the country’s official labour and economic data.

The problem? The tools we use to classify and track industries and occupations in Canada — the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) and the National Occupation Classification (NOC) — are outdated and out of sync with today’s rapidly evolving geospatial landscape.

The Data Systems That Can’t Track

NAICS and NOC codes serve a critical purpose. They allow Statistics Canada, policymakers, researchers, and workforce planners to organize and analyze the labour market. These codes influence immigration policy, education funding, workforce strategies, economic modeling, and more.

But when it comes to geospatial work, they simply don’t fit.

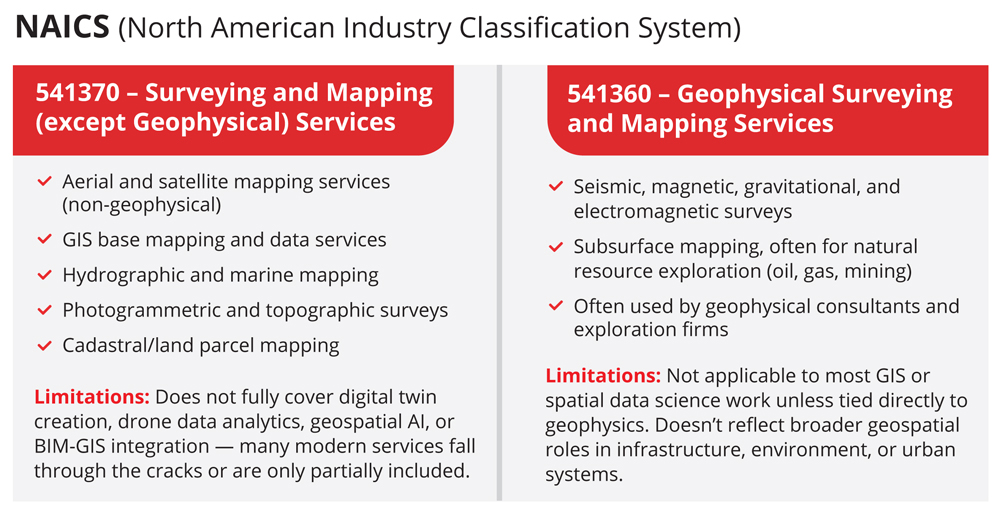

The most commonly used NAICS code for the sector is 541370 – Surveying and Mapping (except Geophysical) Services. This category covers traditional activities like aerial surveying, photogrammetry, cadastral mapping, and GIS mapping. Similarly, 541360 – Geophysical Surveying and Mapping Services includes resource exploration.

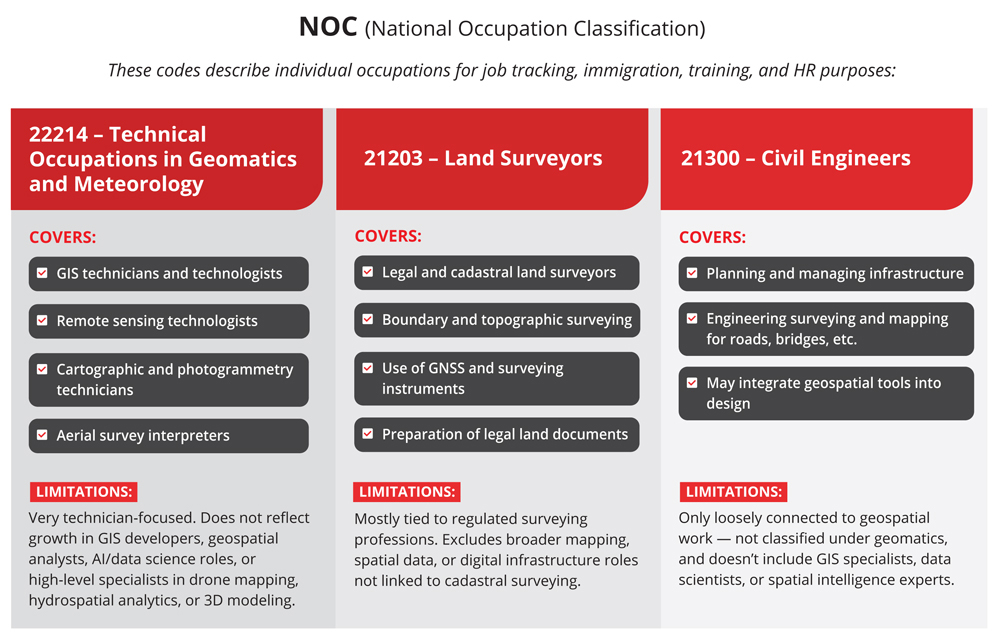

The corresponding NOC codes include:

These categories reflect a decades-old understanding of the geospatial field. They capture surveying and mapping but miss the explosion of new roles and disciplines that have emerged across digital, environmental, and infrastructure sectors, including:

- Remote sensing and satellite data analysis

- Geospatial AI, ML, and data science

- Spatial data analysis predictive modeling

- Hydrospatial and marine geoscience

- Subsurface utility engineering (SUE)

- Digital twins and BIM-GIS integration

- Reality capture and 3D spatial modeling

- Geospatial developers and software engineers

- Location intelligence and smart infrastructure analytics

- Drone mapping and UAV operations

- Real-time spatial analytics for smart cities and emergency response

- Environmental remote sensing for climate/sustainability

These roles don’t fall neatly into existing boxes. They are hybrid, interdisciplinary, and evolving quickly. As a result, they go unrecognized in national labour datasets.

Modernizing the Spreadsheet, Not the Content

In 2021, Canada introduced NOC 2021, the latest revision of the National Occupation Classification. It replaced the older 4-digit codes with a new 5-digit structure and introduced a TEER (Training, Education, Experience, and Responsibilities) system instead of traditional skill levels.

While this was a structural step forward, it did little to address the outdated definitions within the geospatial sector. Roles in geospatial software development, AI, drone operations, digital twin integration, and marine spatial analytics remain poorly defined or absent. The technician focus persists, while advanced hybrid roles are still invisible.

Interestingly, when the federal government needs geomatics services, it turns to a more nuanced approach through the Task-Based Informatics Professional Services (TBIPS) method. Unlike the outdated NAICS/NOC codes, Stream 2 of the TBIPS provides a more accurate framework for hiring geomatics professionals, reflecting the specific needs of modern geomatics projects and the evolving skill set required for them.

However, when assessing and understanding the broader geospatial labour market, the government continues to rely on a generalized and outdated classification system.

If You Can’t Measure It, You Can’t Manage It

There’s a saying that rings true in both business and innovation: “What is not defined cannot be measured. What is not measured, cannot be improved. What is not improved, is always degraded.” The same holds true for Canada’s geospatial workforce. Without accurately defining and measuring the roles shaping this field, we can’t support their growth or ensure they are part of the national strategy for future success.

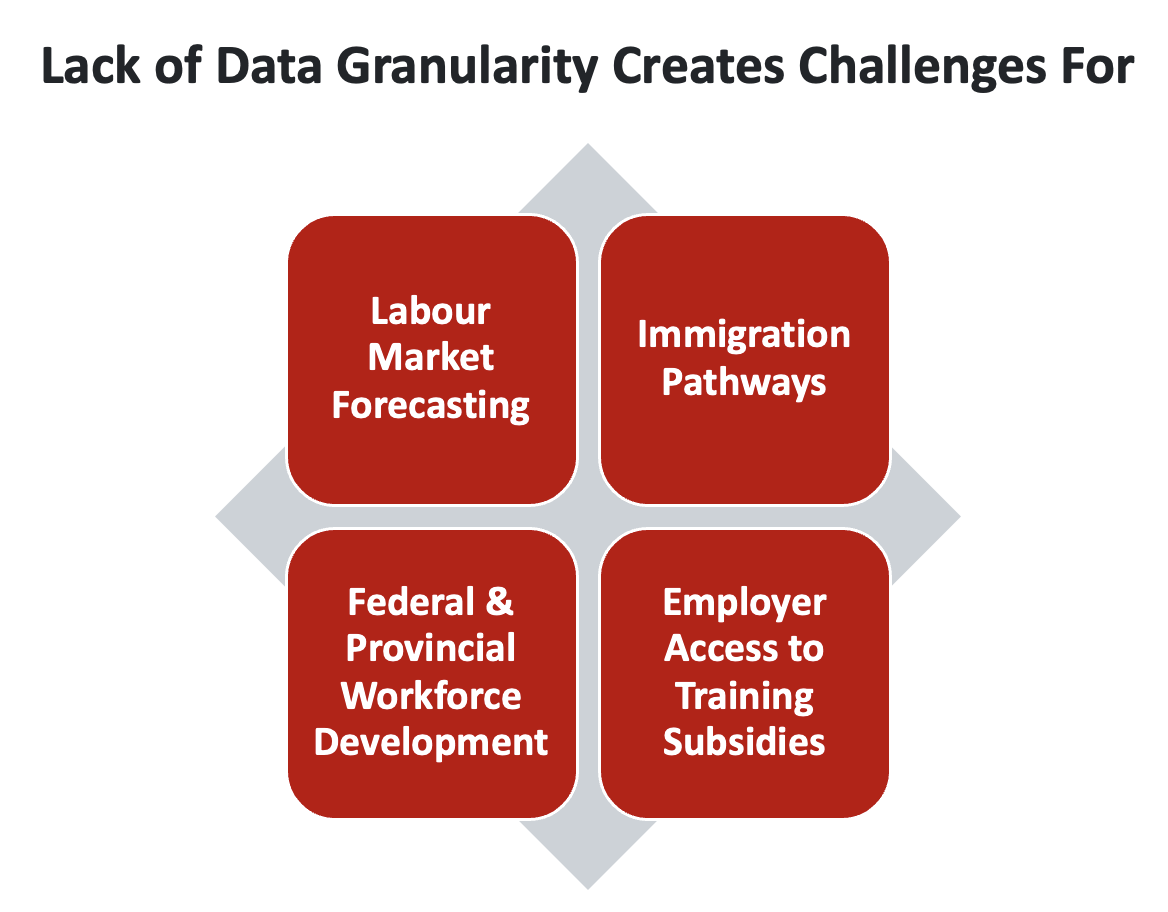

The current classification gap creates a number of problems:

- For employers, it means exclusion from federal wage subsidies, training support, and sector-specific funding programs.

- For workers, it limits access to immigration pathways, job bank visibility, and credential recognition.

- For students and educators, it distorts career pathways and undermines curriculum planning.

- For policymakers, it results in blind spots in economic forecasts, labour market strategy, and innovation policy.

The implications are severe now. As Canada prepares for a new era of nation-building infrastructure projects — from clean energy corridors to digital transportation networks — geomatics professionals are central. Surveyors, remote sensing analysts, UAV operators, digital twin developers, and environment analysts are key to planning, mapping, and managing these assets.

Geospatial data analysis and modeling is an especially fast-evolving area, where professionals leverage AI, machine learning, and big spatial data to forecast risks, simulate infrastructure scenarios, and support real-time decision-making. Yet they remain largely invisible in the workforce strategies being developed to support them.

Data Gaps Paint a Partial Picture

The effects of misclassification are evident in labour market data — or the lack thereof. For instance, according to Job Bank Canada’s 2024-2026 outlook, employment for GIS technicians and remote sensing technologists (NOC 22214) shows a moderate forecast in provinces such as Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Nova Scotia, where employment growth is expected to create new opportunities alongside a modest number of retirements. However, the national picture remains vague, and the broad categorization of roles under this NOC obscures the growing demand for specialized skills in areas like UAV operations, spatial data science, and AI-powered geospatial modeling.

For land surveyors (NOC 21203), the outlook is somewhat stronger. The total number of professionals employed nationally is estimated at 6,000, with good demand projected in Saskatchewan and moderate demand in Alberta and Nova Scotia through 2026.

In reality, there is an urgent demand for skilled geospatial/geomatics professionals across all disciplines. Employers nationwide are increasingly reporting difficulty in finding graduates with the technical skills, certifications, and real-world readiness that the industry requires. In another article, we explore the closure of several geomatics programs, many of which still rely on legacy technologies. Employers are calling for a more adaptable approach to talent development, one that includes broader cross-training in fields like computer science, environmental modeling, and data analytics to prepare the next generation of geospatial professionals.

What about all the roles the NOC doesn’t capture?

For many of the sector’s most dynamic and fast-growing roles, such as geospatial developers, drone operators, data scientists, digital twin specialists, subsurface utility mapping professionals, hydrospatial analysts, and geospatial engineers, no formal labour market data exists. Additionally, positions in geospatial AI, machine learning, real-time spatial analytics for smart cities, and environmental remote sensing for climate resilience are absent from employment forecasts.

These are some of the most in-demand roles in Canada’s infrastructure, climate, and tech sectors — and yet they are invisible in official labour forecasts because no codes exist for them.

As a result, even with rising demand, governments have little means to quantify or support that demand. These blind spots highlight the urgent need to modernize occupational classifications to reflect the growing and evolving geospatial workforce accurately.

Other Countries are Moving Forward

Canada is not alone in facing this issue, but other countries are responding more effectively:

- United Kingdom: The UK’s Geospatial Commission has conducted extensive research on sector needs, including the Demand for Geospatial Skills report, which examined job vacancies from 2014 to 2019 to identify the areas of highest demand for geospatial talent. This is part of their broader strategy to strengthen the sector using real data.

- United States: The U.S. Department of Labor has developed the Geospatial Technology Competency Model (GTCM), which outlines the skills required across data collection, analysis, and application development. The model guides training, curriculum, and hiring, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics has incorporated AI and automation into job forecasts, including geospatial modeling and analytics.

- Australia: Australia has integrated geospatial workforce planning into its national strategy. Geoscience Australia’s Science Strategy 2028 prioritizes early-career geospatial professionals, while the Australian Public Service (APS) Workforce Plan 2025-30 outlines how the country will recruit and grow digital and geospatial talent in the public service.

By contrast, Canada lacks a coordinated effort to define, measure, and project the future of its geospatial workforce.

What Needs to Happen?

Fixing this won’t be easy, but it is essential. A coordinated task force, led by Statistics Canada in partnership with Natural Resources Canada, Innovation, Science and Economic Development, and industry associations, could help Canada catch up to where the sector already is.

This isn’t just a bureaucratic issue but encompasses national competitiveness.

Geospatial professionals are essential to Canada’s ability to plan resilient infrastructure, adapt to climate change, manage land and marine resources, and build intelligent digital systems. They work in government agencies, tech companies, Indigenous communities, startups, utilities, agriculture, etc.

Canada has the talent. It has academic expertise, industry innovation, and a growing list of national priorities that depend on geospatial insight.

But if we can’t see them in our data, we won’t fund them. If we don’t classify them, we can’t attract or retain them. And we risk falling behind countries already investing in their spatial intelligence capabilities.

Be the first to comment