Canada’s failure to invest in modern geodetic infrastructure has left it dependent on foreign systems to run satellites, guide ships, synchronize power grids, and safeguard sovereignty — an invisible weakness in the infrastructure that holds the nation together.

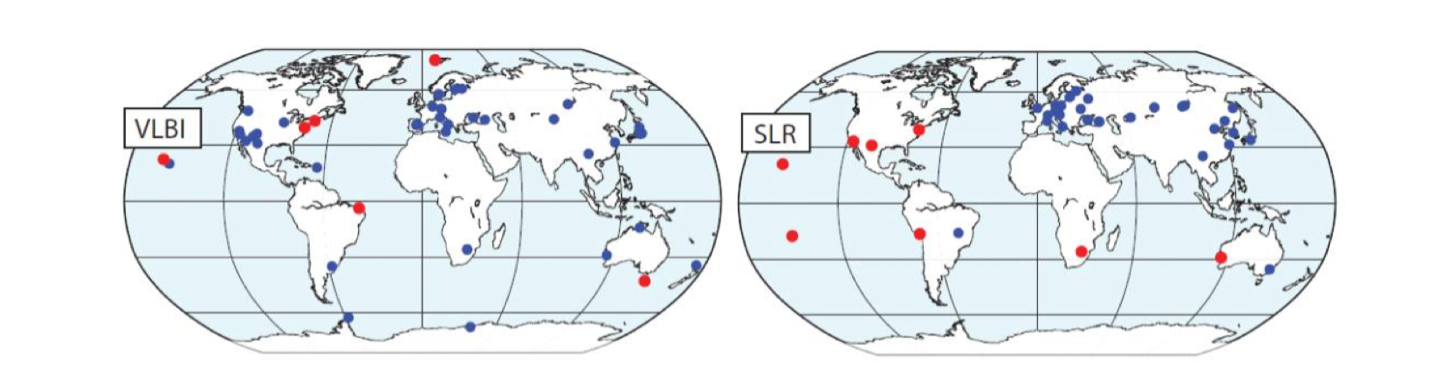

On the global maps of geodetic observatories (below), Canada, the world’s second-largest country, is almost a blank space. Europe, Japan, and Australia are dense with dots. The United States dominates North America. But on the key networks of Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) and Satellite Laser Ranging (SLR) — the backbone of the world’s geodetic infrastructure — Canada looks no different from Africa: both vast, both empty, both absent.

That absence is not just a cartographic embarrassment. It places Canada closer to the developing world than to its peers in a science that underpins every satellite in orbit and every digital service on Earth. And as satellites proliferate, climate shifts accelerate, and geopolitics hardens, Canada’s neglect of space geodesy is becoming not just a technical liability but a sovereignty crisis.

The Invisible Science Holding the World Together

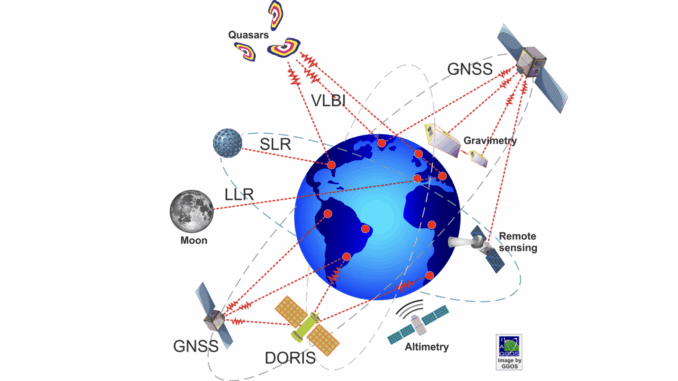

Geodesy is the science of measuring Earth’s shape, gravity field, and orientation in space and their changes over time. To most people, it is invisible. To satellites — and to the systems that depend on them — it is indispensable. Geodetic space techniques are required to know the Earth’s orientation in space, which defines the reference used in navigation.

Every time a plane takes off, a ship navigates, a stock exchange timestamps a trade, or a mobile phone connects to a tower, it is using Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) services. These services require constant updates, because the Earth is never still: it spins, wobbles, and drifts under the pull of oceans, atmosphere, and climate change. A single millisecond error in Earth’s rotation parameters can translate into a 600-meter miscalculation of a satellite’s orbit.

The United Nations Hidden Risk report makes the stakes clear: “It is essential that geodesists constantly make these observations and provide updated geodetic products for satellite operations; without which the satellite applications society takes for granted would degrade or fail.”

In the United States, the Department of Homeland Security has found that 15 of 18 critical infrastructure sectors rely on GPS, including telecommunications, emergency services, and financial exchanges. Without geodesy, those services unravel.

The Hidden Risk

GNSS timing signals keep cell towers synchronized, stock exchanges accurate to the microsecond, and power grids balanced across entire regions. Without them:

- The operation of mobile phone networks would be impossible.

- Stock exchanges would have reduced protection for investors.

- The daily operation of power grids would be more difficult and labor-intensive.

The financial stakes are immense. The UK government has estimated that a seven-day GNSS outage would cost about €8.9 billion. In the U.S., the daily loss was estimated at $1 billion as per a 2019 report.

Yet despite this dependence, global investment in the geodesy supply chain is vanishingly small. The UN Hidden Risk report estimates that only €60-90 million per year is invested globally, which is less than 0.05% of GNSS/EO revenues.

Canada’s Borrowed Sovereignty

Every G7 nation except Canada has invested in sovereign geodetic infrastructure. The United States operates the Naval Observatory, while Europe maintains multiple ground stations, and Japan and even Australia contribute observatories and analysis centers.

Canada, by contrast, contributes very little. Its satellites and critical infrastructure depend on Earth orientation parameters supplied by the U.S. Naval Observatory and the International Earth Rotation Service — services that are voluntary, not guaranteed.

This reliance extends beyond engineering into politics and sovereignty. If the United States decided tomorrow to restrict access — in the name of national security, trade leverage, or escalating geopolitical tensions — Canada would have to rely exclusively on voluntary services from overseas.

This is not alarmism. In recent years, Washington has walked away from climate agreements, rewritten trade frameworks, abandoned arms treaties, and scaled back commitments to multilateral institutions. If it can backtrack on treaties, it can backtrack on voluntary geodetic data streams.

For Ottawa, sovereignty cannot rest on the hope that Washington will always provide.

RADARSAT’s Lost Potential

The absence of Canadian geodetic observatories has direct consequences for its own space program. RADARSAT, once a symbol of Canadian leadership in space, is today the only major commercial synthetic aperture radar mission not supported by the International Laser Ranging Service.

The difference translates to precision. ESA’s Sentinel-1, tied into the International Laser Ranging Service, achieves centimeter-level orbit accuracy. RADARSAT, without that link, is limited to the decimetre scale — a shortfall that makes routine interferometry unreliable.

As a result, Canadian agencies now depend on Sentinel for day-to-day InSAR monitoring — an extraordinary irony for a country that pioneered spaceborne radar.

The Defence Spending Paradox

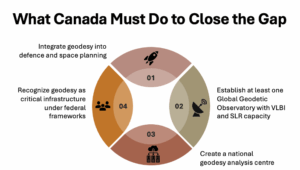

The timing makes the neglect even more glaring. Canada has committed to raising defence and preparedness spending to 5% of GDP, a nation-building investment on a scale not seen in decades.

Billions are earmarked for ships, fighter aircraft, satellites, and new infrastructure. But none of that funding has been directed to geodesy yet.

Unlike radars or ships, geodetic observatories are not recognized as critical infrastructure. Yet without them, none of those assets can operate independently.

The paradox deepens with Canada’s space ambitions. A commercial launch facility is already under development in Newfoundland and Labrador, billed as a milestone in sovereign access to space. Yet without a Global Geodetic Observatory, every satellite launched from Canadian soil will still depend on foreign geodesy services to determine its orbit.

The UN’s Hidden Risk brief is explicit: countries must “officially recognize and resource the global geodesy supply chain as critical national infrastructure”. Until Canada does, even its most visible space investments rest on borrowed sovereignty.

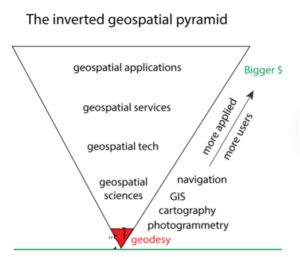

The Inverted Pyramid

The fragility of geodesy is not unique to Canada. The Geodesy Crisis paper in the United States warned that “geodesy has become an invisible science” and that “its decline threatens our national security and poses major risks to an economy strongly tied to the geospatial revolution.”

Its authors coined the metaphor of the “inverted pyramid”: at the narrow tip lies geodesy, supporting a trillion-dollar global economy of satellites, services, and applications.

But because the money is concentrated at the top, the scientific base has been starved. “The present global economic value of that pyramid is roughly $1 trillion per year… while its tip or base is crumbling, threatening the integrity of the entire edifice.”

Canada today exemplifies that warning. Years of budget cuts have left its domestic geodesy programs understaffed, with shrinking training opportunities and a steady outflow of graduates to the United States and Europe. The country operates at the top of the pyramid — satellites, applications, commercial products — without investing in the scientific base that sustains them.

A World Moving Ahead

Canada’s position contrasts sharply with steps taken elsewhere.

In 2022, the United States committed $25 million to reinforce its national geodetic capacity. That investment followed Congressional hearings sparked by the Geodesy Crisis white paper, submitted in 2020 to the U.S. National Academies’ Decadal Survey for Earth Science and Applications from Space (ESAS 2022–2032). Authored by geodesists from NASA Goddard, the U.S. National Geodetic Survey (NOAA/NGS), and leading universities, the paper warned that geodesy had become an “invisible science” — the fragile tip of an “inverted pyramid” sustaining a trillion-dollar global economy.

Europe sustains a dense network of VLBI and SLR stations through ESA and national agencies, supporting missions like Sentinel-1. Japan’s Geospatial Information Authority continues to operate major observatories such as Tsukuba, while Australia’s Yarragadee site remains one of the world’s most important SLR stations. China has gone further still, pouring resources into academic programs and infrastructure and now producing more PhD geodesists than the rest of the world combined.

What’s at Stake

Canada’s absence in space geodesy is not an abstract technical gap. It touches every sector that relies on precise positioning and timing — from aviation and telecom networks to banking systems, power grids, and defence. The UN Hidden Risk report has already warned that “satellite services are at risk of degradation or failure due to the lack of resources provided to the global geodesy supply chain.”

The geodesy crisis is a global issue, but unlike its G7 peers, which at least sustain observatories and contribute to the global system, Canada has yet to take meaningful steps of its own. It remains dependent on voluntary data from abroad — and the sovereignty cost of that delay grows sharper with each passing year.

In space and on Earth, Canada’s navigation parameters are being defined by others. Sovereignty cannot rest forever on borrowed data.

Be the first to comment