The first time I traveled to Nunavut, I was told the region I was going to was a hamlet called Kugaaruk. Driving through the town with our local guide, I noticed the radio station was entirely in Inuktitut. Even as a visitor to this area, the local news didn’t feel like just background noise on our drive, but a reminder of the language and culture of northern Canada. Later, when I returned home and told my family about my trip, it was the first time I had heard the region referred to as “Pelly Bay”. This was a surprise as I had never heard this name before. To me, it has always been Kugaaruk, and in my mind, it always will be. That name, in the original language of the people living there, will always be the default for me.

Experiences like this help show how deeply important Indigenous place names are, not just as labels on a map, but as reflections of the land’s true heritage. Especially in the North, where colonial names have long overwritten traditional ones, restoring Indigenous names is a powerful act of cultural reclamation. It shifts the Canadian narrative from cultural erasure to one of recognition and respect. With increased accessibility to traditional names, our first introduction to a place becomes grounded in Indigenous heritage, making it easier for everyone to know and use a region’s true name.

That same shift in perspective became even clearer while working with communities like Tuktoyaktuk, or Tuktuyaaqtuuq, in the Northwest Territories. This name translated to English, means “resembling a caribou”. Formerly named Port Brabant, in 1950 it became the first Canadian community to officially reclaim its Indigenous name. That change was symbolic of reclaiming identity, language, and connection to the land.

Using traditional names helps create space for language learning, builds respect for Indigenous culture, and reinforces the idea that we are visitors on these lands. As a non-Indigenous Canadian, the act of choosing to use a place’s original name is a simple but meaningful way to acknowledge its history.

It’s a lot like the respect we show when learning to pronounce someone’s name correctly. As someone whose own name is often mispronounced, I know how meaningful it is when someone asks about the correct pronunciation. It’s a small but purposeful show of respect, and something we can easily extend when visiting a new place. These aren’t just words on signs or labels on maps, but are tied to the history of the land and the relationship with those that reside. For example, the translation of Kugaaruk means “little stream”, referring to the brook that runs through the community. Knowing the traditional name helps shift how we see a place as something more than a point on a map, it paints a clearer image of the environment itself.

Talking about these names and using them in everyday contexts can help bring Indigenous languages back into public awareness. It creates space for learning, curiosity, and cultural connection. Using names with these sorts of cultural and environmental ties is one small, meaningful way to acknowledge and respect the deeper history of the land, especially for non-indigenous Canadians.

Recent Updates to Canada’s Living Atlas

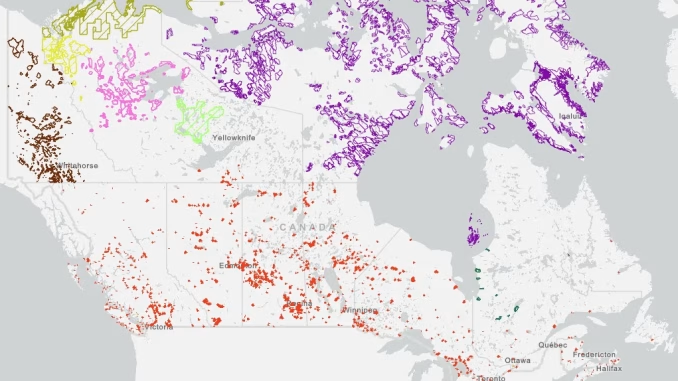

Recent updates to Canada’s Living Atlas marks a shift in integrating Indigenous into national mapping platforms, with a collection of 30,000 place names in over 60 different Indigenous languages now included.

Key datasets include:

- Indigenous Geographical Names dataset: Representing the traditional names across Canada.

- Indigenous Lands & Treaty Boundaries: Highlighting historic and modern treaty areas and land agreements.

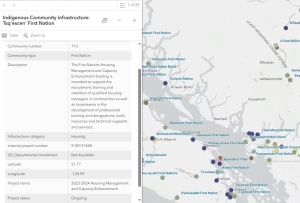

- Community Data: Describing locations of community resources such as Tribal Councils, infrastructure projects, and energy sources in remote areas.

- Resource Data: Compiling mining agreements and other protocols

What makes this especially significant is that these datasets are continuously updated, not frozen in time, but are living documents. Databases such as the Remote Communities Energy Database and Indigenous Community Infrastructure dataset can help track community need as well as long-term growth across regions.

For remote and rural regions, which are often underrepresented or missing in mainstream data, this inclusion is significant. Whether it’s for planning, conservation, community development, or education, having access to dynamic data supports more informed community initiatives.

As digital mapping continues to shape how we perceive and interact with the world, the responsibility to represent places accurately and respectfully grows. These new Indigenous-based datasets are more than just data, but a step forward for Canadians in acknowledging our past and the history of the land we interact with. As visitors of this land, it is only right to reflect on the cultures that existed long before us and recognize the original stewards and the history that shaped the land we know today.

What had started as a simple introduction to a hamlet became a lesson on the significance of names. It revealed how names shape understanding, and how much meaning they can carry. Even the name Canada comes from the Iroquoian word Kanata, which English translation means “village” or “settlement” highlighting how Indigenous languages are central to the very identity of our country. Using and sharing Indigenous names isn’t just an act of respect but a step toward recognizing the full story of the land we call home.

Be the first to comment