The geospatially-inclined might not typically think of linguistics as within their purview. However, approaching human language from a geographical perspective can be both practical and fascinating.

The term geolinguistics refers to the use of maps in linguistic research. This might include the distribution, diversity, evolution, and dynamics of languages. Although the field has been of interest primarily to linguistic researchers, it opens up opportunities for the broader geospatial community to engage in original, interdisciplinary work.

Evolving with geospatial technology

The concept of geolinguistics is not new. The field of linguistics has long been of interest to geographers. Likewise, spatial variation of language is an established topic of linguistic research. Rather than viewing geolinguistics as an entirely new field, we can consider how the study of language has co-evolved with cartography and GIS.

An early example is Jules Gilliéron’s Atlas Linguistique de la France (1902-10) which mapped Romance dialects. In North America, the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States (LAMSAS) evolved from language mapping efforts beginning as early as the 1930s. The Ethnologue project has been active since 1951 and remains a vital source of geographic information for the world’s over 7,000 languages.

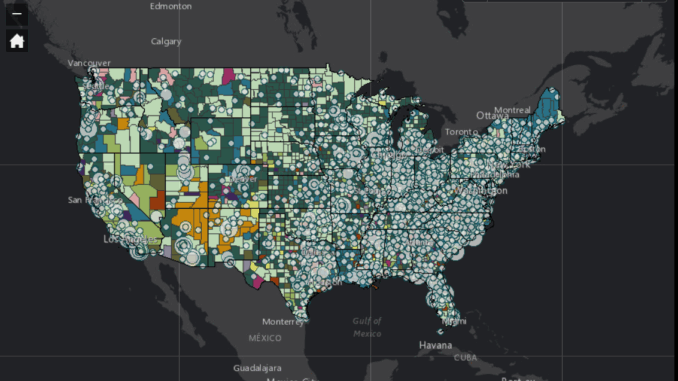

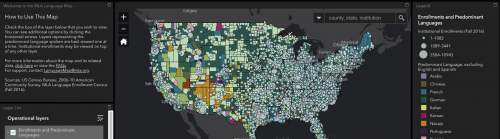

Geolinguistic applications grew with Web 2.0 to add interactivity and data exploration. For instance, the Modern Language Association (MLA) Language Map uses ESRI’s ArcIMS to display the locations and numbers of speakers of languages commonly spoken in the US.

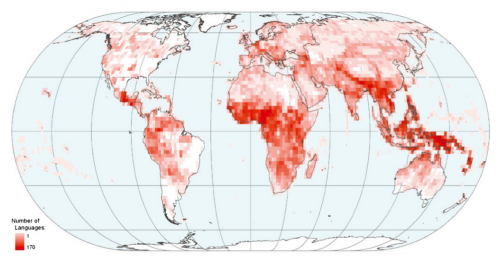

Linguistic research has also leveraged improved geospatial datasets, allowing for the identification of statistically significant correlations between language and physical and social variables. For instance, Amano et al. (2014) used mapping techniques to identify variables associated with endangered language extinction. Along similar lines, there has been work to map the co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity (e.g., Gorenflo et al 2012). More recently, researchers found a remarkable spatial convergence of grizzly bear population genetics and Indigenous language groups in British Columbia (Henson et al. 2021).

Challenges and prospects

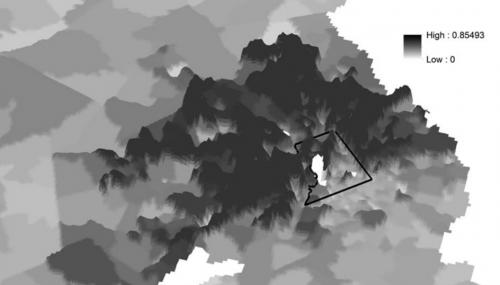

The spatial depiction of languages raises practical and conceptual challenges. Many language atlas examples use choropleth mapping with polygons and discrete boundaries. This is inconsistent with gradations and fluidity of language usage in practice. Granted, there are established geospatial techniques to deal with indeterminate cartographic boundaries, such as probability surfaces and fuzzy set membership functions. However, established guidelines for language mapping are lacking.

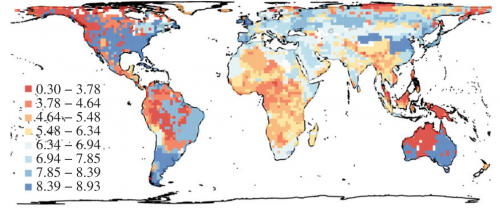

Luebbering et al. (2013) point out that language maps often inaccurately show one language per place. As an alternative, these authors propose a three-dimensional raster model of linguistic diversity.

Given the community-rooted nature of languages and cultures, perspectives from participatory and critical GIS are important to integrate into geolinguistic practice. The true potential of the field is not in detached research, but in engaging communities and perspectives on how digital technologies might evolve in more culturally-aware ways.

There are many examples of how digital technologies are being used for cultural-linguistic education, preservation, and revitalization. While there may be promise for web 3.0 developments to further these efforts, current paradigms (e.g., data centralization, big tech, bias in AI) might lead one to be critical.

These are vast, complex discussions that the geospatial community can help enrich.

References

Amano, Tatsuya, Brody Sandel, Heidi Eager, Edouard Bulteau, Jens Christian Svenning, Bo Dalsgaard, Carsten Rahbek, Richard G. Davies, and William J. Sutherland. 2014. “Global Distribution and Drivers of Language Extinction Risk.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281 (1793): 17–19. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1574.

Goebl, Hans. 2006. “Recent Advances in Salzburg Dialectometry.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 21 (September): 411–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fql042.

Gorenflo, L. J., Suzanne Romaine, Russell A. Mittermeier, and Kristen Walker-Painemilla. 2012. “Co-Occurrence of Linguistic and Biological Diversity in Biodiversity Hotspots and High Biodiversity Wilderness Areas.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (21): 8032–37. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117511109.

Henson, Lauren H., Niko Balkenhol, Robert Gustas, Megan Adams, Jennifer Walkus, William G. Housty, Astrid V. Stronen, et al. 2021. “Convergent Geographic Patterns between Grizzly Bear Population Genetic Structure and Indigenous Language Groups in Coastal British Columbia, Canada.” Ecology and Society 26 (3). https://doi.org/10.5751/es-12443-260307.

Hoch, Shawn, and James J. Hayes. 2010. “Geolinguistics: The Incorporation of Geographic Information Systems and Science.” Geographical Bulletin – Gamma Theta Upsilon 51 (1): 23–36.

Luebbering, Candice R., Korine N. Kolivras, and Stephen P. Prisley. 2013. “Visualizing Linguistic Diversity through Cartography and GIS.” Professional Geographer 65 (4): 580–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.825517.

Be the first to comment