Canada’s commitment to ramp up defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2035 may be the headline, but it’s the infrastructure component – 1.5% of GDP – that carries long-term implications for how the country will operate and compete in a turbulent world. Unlike earlier infrastructure pushes tied to economic stimulus or post-pandemic recovery, this effort is rooted in something deeper – the need to reinforce Canada’s sovereignty and resilience through physical and digital infrastructure that addresses current geopolitical shifts.

The 1.5% component is for “broader defence-related industry and infrastructure,” which includes critical infrastructure protection, network defence, civil preparedness, innovation, and strengthening the defence industrial base.

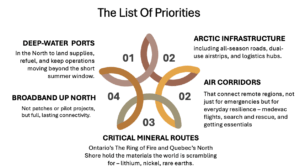

This is about ports and airports in the North, roads to remote critical mineral deposits, secure networks for emergency communications, and logistics capacity to serve both military and civilian needs.

Strategic Geography of a Changing Canada

Historically, Canada’s infrastructure investment has concentrated along a narrow economic corridor – from Windsor to Quebec City, tethered to U.S. markets and priorities. This plan begins to challenge that dependence, favouring an east-west and northward strategy that strengthens internal connectivity, Arctic sovereignty, and access to underdeveloped regions.

And yes, it’s also about reducing overdependence on the U.S. corridor and creating meaningful alternatives for movement, trade, and national coordination.

The proposed 1.5% of GDP allocation for defence-related infrastructure – roughly C$50 billion annually by the 2030s – is more than a policy shift. It’s a structural rethinking of where and how Canada invests to secure its future.

Beyond Defence: Long-Term Economic Dividends

While the plan is framed through a defence lens, the potential economic spillover is enormous. A deep-water port that supports Arctic patrols will also support Indigenous trade and climate science. A secure data network may anchor both national defence and regional tech innovation.

According to the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, every C$1 billion invested in infrastructure supports roughly 18,000 jobs — direct and indirect. If the federal government spends C$50 billion annually on defence-related infrastructure, as projected, the economic impact could approach 900,000 jobs per year at full rollout.

That level of investment would reverberate across various industries, including construction, transportation, technology, and clean energy, while reinforcing Canada’s long-term posture. This is not incremental patchwork, but about making long-term bets on the systems that will shape where and how Canada thrives.

The strategic shift toward the North marks a long-overdue course correction. For decades, Arctic development has been piecemeal, shaped more by federal hesitation than ambition. But rising temperatures are changing the Arctic faster than most expected. Sea ice is thinning and new routes are opening. And other countries, especially China and Russia are watching closely.

None of this is new. Canada’s known the risks for years. But now it’s harder to ignore: sovereignty in the North depends on infrastructure. If you can’t reach it, you can’t protect it.

The Tłı̨chǫ All-Season Road is a good example. Completed in 2021, it provided remote communities with year-round access. Trucks can get through in February. Medics, too. That road didn’t just shorten travel time — it changed what’s possible.

The same logic applies to Arctic ports, forward-operating airstrips, and resilient communication links. Without these, patrol ships can’t resupply, aircraft can’t land, and federal agencies can’t operate effectively in some of the most strategically vital terrain in the country.

In many parts of the North and rural Canada, even basic connectivity is missing. Broadband remains spotty. Satellite service is expensive and unreliable. Yet secure, high-speed communications are critical – not just for daily life and local business, but for command-and-control, situational awareness, and the ability to respond to crises quickly and in coordination.

Geospatial Imperative: The Foundation Behind the Build

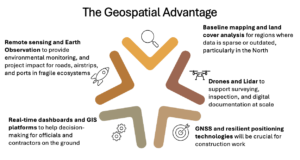

No infrastructure build of this scale can move forward without geospatial intelligence at its core. The success of Canada’s defence-related infrastructure strategy will depend on how well we map, model, monitor, and manage the physical and digital spaces we intend to transform.

Many of the areas targeted for development – the Arctic coastline, remote mineral corridors, northern airstrips – are places where baseline mapping is incomplete, environmental conditions are shifting rapidly, and access is inherently difficult.

Before a single shovel hits the ground, geomatics professionals will be needed to chart the terrain, assess risks, and define how infrastructure can coexist with permafrost, wetlands, and protected habitats. That includes working with Indigenous communities, whose mapping knowledge and partnerships are essential to getting it right in the North.

Location technology will also underpin construction and long-term operations. From Lidar and drone inspections to GNSS-based surveying and digital twins, geospatial tools will guide every phase of the projects. Real-time GIS dashboards will facilitate coordination among federal agencies, contractors, and local communities, particularly in complex logistics and tight timelines.

For the geospatial sector, this is more than a support role — it will be the core pillar of execution. Every element of this infrastructure wave, from planning through to maintenance, will depend on accurate, timely, and accessible location data.

But the industry must also confront its own bottlenecks. Labour shortages in geomatics are already emerging. Procurement processes don’t always account for the geospatial component of infrastructure delivery. And without coherent national data standards, efforts to share or integrate spatial information across jurisdictions can stall.

There’s also a more fundamental question: are we investing enough in the geospatial infrastructure itself? Data fragmentation remains a persistent issue. Without shared standards, open access to foundational datasets, and integration mechanisms between federal, provincial, and Indigenous data systems, the result will be inefficiency and duplication.

If this nation-building effort is to leave a lasting digital legacy, then the way we manage and sustain geospatial assets needs to evolve.

This moment is a generational opening for Canada’s geomatics community to lead – not just by responding to contracts, but by helping shape how we build, measure, and sustain the infrastructure of a more sovereign and connected Canada.

If we get it right, the benefits will far outlast the current political cycle. But only if we have the vision – and the capability – to build for the long term.

ALSO READ: OUR COVERAGE ON CANADIAN GEOSPATIAL ECOSYSTEM

- Geospatial Infrastructure: Canada’s Defense Strategy Ignores a Critical Layer

- Canada’s Blind Spot: The Government Can’t See Its Own Geospatial Sector

- Canada Must Leverage Its Geospatial Legacy to Embrace New Opportunities

- Treat Geomatics Like a National Asset, Not an Afterthought

- Sovereign Data Infrastructure: What It Is and Why It’s Critical for Canada

- Taking Control of Canada’s Digital Sovereignty with Open-Source GIS

- Navigating the Future: Why Canada Needs a Sovereign GNSS

- U.S. Tariffs Could Push Canada Toward a Stronger Role in Multi-Polar Space Economy

Be the first to comment