New Years is a time to reminisce about the past year and compile your thoughts. What better way to do so then to reflect on your 140-character opinions. One thought that continually pops into my mind is a tweet I sent out back in July:

I still cannot comprehend is the fact some major Canadian cities still do not have address and location information readily available via GPS receivers for their front-line emergency response units. How can someone legitimize OC Transpo having GPS receivers to drive capital-city citizens around? And yet if your house is on fire, sorry, but sure hope that the emergency response drivers can determine your address on a paper map, because there is no geodatabase for them to use.

There are a variety of difficulties that are associated with addresses and locations. There can be multiple Main Street’s in one city, especially with amalgamated cities, and similar full addresses within a province. Deliveries to my parents address routinely requires advanced instruction to their house post-amalgamation, where couriers utilize the same street number, name and street type are throughout their city. Another issue is for streets that have multiple names.

You know when you use Google Earth and it says merge on to Chemin Valley/QC-105 S. If I wasn’t lost before now I sure am. Not only is there an issue with what street name am I looking for, but also how does a geodatabase handle multiple street names for a single entity? A second table is used for all other names used besides the linear shape geographic feature class for the street. But still, this adds in yet another roadblock (yes, pun intended) that a GIS user must take into consideration when naming streets within a database.

Aside from the multiple complications that addresses and locations make for GIS users, additional issues arise when life or death is on the line. One could argue that response time is one of the most crucial components to EMS service successes. Response time elements include recognition of an incident requiring 911 services, the phone call to request for EMS, acquiring the accurate location of the phone call and incident, and the time duration that EMS takes to travel from the station to the area of concern. Two of these components require geomatics.

Acquiring the accurate location of a phone call is not as simple as it may seem. When a call is initiated from a landline, more accurate details are available compared to calls from a mobile device. CBC states that operators can have instant access to a name, address and phone number when an individual calls from a landline phone. “The increasing number of cellphones being used in favour of traditional landlines can compromise public safety, emergency dispatch operators say” (CBC, 2012). Out of all Canadian households, 13% reported using only a cellphone in 2010, and 50% of households in the 18-34 age range were only using cellphones. This means that half of this age bracket does not have a landline at their disposal. Lori Powers, the director of 911 dispatch centre in Windsor, Ontario explains that the accuracy of a cellphone location can vary three or four city blocks, sometimes thousands of metres dependent on the cell tower location (CBC, 2012).

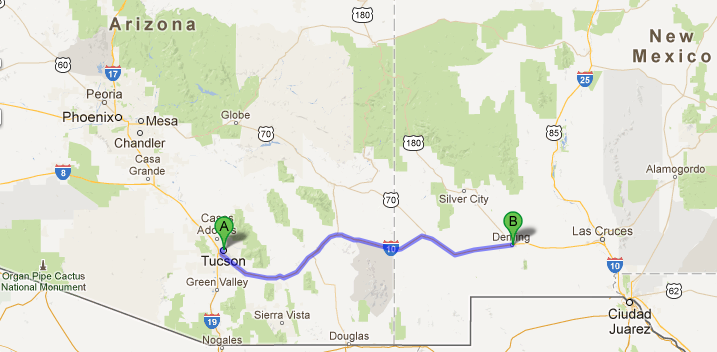

There have been multiple instances where calls were rerouted very far from the initial place of contact. The Savannah Morning News published a story that affected emergency call routes. Approximately 100 911 calls were directed to Savannah, even though they were intended for Atlanta. An AT&T cell tower in Atlanta was coded with a Savannah address; therefore the calls were not being directed properly. More than 70 calls were misrouted before police officials discovered the problem. This incident occurred in June 2011, but a similar situation happened in late October 2012 in Tucson, Arizona.

Source: Google Maps, 2013.

A citizen in Tucson, Arizona called 911 via a cellphone to report a man who had fallen and cracked his head. He gave the address as East Broadway, and confusion began between the dispatcher and the witness. The dispatcher was hundreds of kilometres away in Deming, New Mexico, and finally at 1 minute and 24 seconds into the call, the witness stated a landmark near him – a mall. The cellphone company provider was performing maintenance on the towers nearby, which may have caused the rerouting.

Another element of EMS response time is the time duration that EMS takes to travel from the station to the emergency situation. This can require the most basic form of GIS – map reading. For cities that do not have GPS receivers installed on the response vehicles themselves, the drivers must be well aware of the city’s streets. They must remain up-to-date on one-way changes, on land parcel and address changes and new roundabouts and street light additions. For cities that do have GPS receivers at their fingertips (literally), it is essential that their databases are consistently updated and maintained, so that a reliance on the technology does not backfire. Additionally, speed limits and traffic conditions can be brought in to provide more detailed information.

Further positive aspects of advanced technology are how more and more drunk driving incidences are being reported, considering citizens have access to mobile devices. As with any form of technology, it will always be advancing. I believe that with anything new, it must be tested and reviewed meticulously, especially when lives are on the line.

Be the first to comment