Over hundreds of thousands of years, the Earth — along with its climate, topography, and terrain — has undergone profound transformations driven by both natural forces and, more recently, human activities.

Long-standing climatic conditions in various landscapes are shifting, enabling new plant species to thrive in areas where they previously could not grow, while traditional species that have existed for centuries are disappearing. These evolving conditions are giving rise to new ecological realities.

In Canada, the climate is undergoing significant and accelerating changes that are reshaping the very fabric of its natural environments. Among the most prominent changes are an increase in average temperatures of 1 to 3 degrees Celsius across the country, as well as an increase in precipitation of approximately 0 to 30%.

There is a shift in vegetation paralleled by terrain changes such as thawing permafrost in the North, increased soil erosion, and altered hydrological systems—all of which further influence what can grow and where.

What is Plant Hardiness, and How is it Zoned?

The hardiness of a plant refers to its capacity to withstand challenging growing conditions, including cold temperatures. Key factors that are usually assessed to determine hardiness include cold, heat, drought, flooding, and strong winds. Additionally, characteristics such as latitude, longitude, and elevation of the area play a role in defining a plant’s hardiness zone.

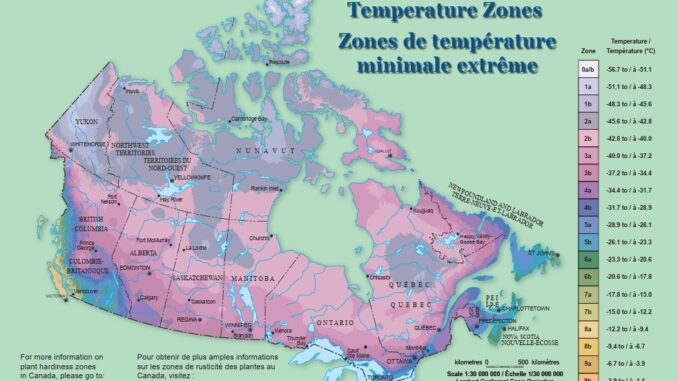

To help plants thrive in a favorable environment, including appropriate location and temperature, plant hardiness systems have been developed for various regions around the world. In the 1960s, Canada created a multivariate plant hardiness index that considers various factors related to temperature and precipitation, along with snow depth and wind speed. It is then categorized into zones ranging from 0 to 9, based on climate conditions.

Let us see how it works.

- Zone 0 encompasses the coldest regions of northern Canada, indicating that only the hardiest plants can thrive in this environment.

- Zone 9 encompasses relatively warmer regions of Canada, such as Vancouver Island. This climate allows for a much wider variety of plants to thrive in this zone.

Let us delve into a little more detail about how these climate variables play a vital role in maintaining these zones.

- The lowest average daily temperature occurs in the coldest month of that region.

- Length of periods above 0°C.

- The amount of rainfall from June to November.

- The highest average daily temperature during the hottest month of the zone.

- Severity of Winter.

- Average maximum snow depth and wind gusts over the past 30 years.

Updated Hardiness Zone Maps

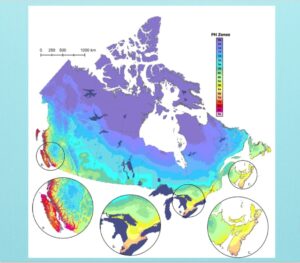

In light of these interconnected shifts, tools like the updated version of “The Plant Hardiness Zone Map” play a crucial role, offering an evidence-based tool to understand and adapt to the developing conditions. They offer a science-based approach to understanding climate-driven changes in vegetation zones, providing valuable guidance to gardeners, farmers, conservationists, and policymakers.

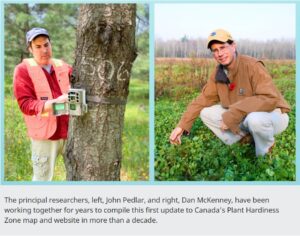

Researchers Dan McKenney and John Pedlar from the Canadian Forest Service, who specialize in plant hardiness, have managed multiple updates to the hardiness zone map in recent decades.

These researchers suggest that the updated maps reveal minor yet notable warming changes in different parts of Canada. Certain regions have moved by half a zone, while others have seen changes of as much as two zones.

If you take a closer look at the map above, Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories, which was previously classified as zone 0b, has now been reclassified to zone 1b, indicating a full zone increase. This change implies that there may be opportunities for new plant species to thrive in this region.

Low hardiness ratings are typically observed in the far northern areas and in the mountainous regions, such as the Canadian Rockies along the British Columbia-Alberta border. More subtle effects of elevation can also be observed across the country, including in Duck Mountain near the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border, the Algonquin Highlands in southeastern Ontario close to the Quebec border, and the Laurentian Mountains north of Quebec City.

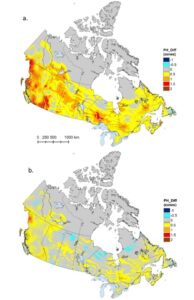

According to the map on the right, which is divided into sections (a) and (b), much of southern Canada has seen an increase in Canadian hardiness zone ratings compared to the 1961–1990 period. The most significant increases, reaching up to 2 full zones, are found in western Canada, especially in southern and northwestern British Columbia. The far northern regions of the country remained unchanged, as the hardiness index is not designed for the extremely cold conditions there, and therefore does not account for any warming that may have occurred.

Nonetheless, there were some areas where hardiness ratings decreased by half a zone, including parts of northeastern Newfoundland, the western coast of Vancouver Island, and a few small areas in the Prairie provinces, as shown in section (a) of the map. Similar, albeit less pronounced, changes were observed when comparing the current hardiness map to the one created for the previous climate normal period of 1981–2010 (b).

Additionally, individual species maps are also available for thousands of plant species. These comprehensive maps demonstrate recent advancements in species distribution modeling (SDM), a technique employed to forecast potential habitats for a species by considering both present and forecasted climatic conditions.

What’s Next?

In Canada, plant hardiness zone maps will keep changing due to shifting climate conditions and weather trends. With advancements in technology, there will be more chances to accurately identify the specific plant hardiness zones.

The upcoming project aims to create a heat map that shows different temperature ranges and how they affect various plant species throughout Canada. While current assessments of plant hardiness in Canada take into account maximum temperatures, they do not specifically address the risks posed by heat to plants.

In response to upcoming hardiness zone forecasts, distribution models for thousands of native and ornamental plant species have been created and are still being refined. This effort would greatly improve with increased cooperation between the nursery sector and scientific modeling organizations.

As climate change progresses, it is anticipated that the Canadian plant hardiness system will eventually exceed the climatic boundaries for which it was initially designed.

Be the first to comment