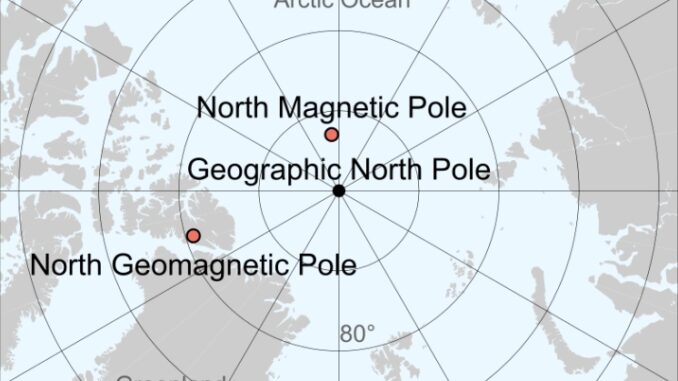

From the GPS in your phone to the navigation systems guiding aircraft and ships, our modern world depends on knowing exactly where “north” is. But here’s the twist — there isn’t just one north. There are two, and they don’t always agree.

True north (or geographic north) is the unchanging point where Earth’s axis of rotation meets the surface in the Northern Hemisphere. In contrast, magnetic north is the direction in which Earth’s magnetic field points, a position that constantly shifts due to the swirling molten iron deep within the outer core. These shifting magnetic “flux lobes” cause magnetic north to wander—sometimes slowly, sometimes at surprising speeds.

But what has truly caught scientists’ attention is its speed. In recent decades, the magnetic North Pole has been moving away from Canada at an unprecedented rate. This unusual behaviour has sparked a wave of questions and speculation.

Knowing the difference between true north and magnetic north is one thing — but what’s truly fascinating is how magnetic north has resisted staying still.

The History of it

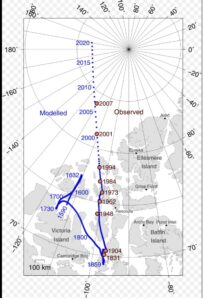

Early European explorers, mapmakers, and scientists thought that compass needles were drawn to a fictional “magnetic island” located somewhere in the far northern regions. The North Magnetic Pole was first discovered in 1831 by James Clark Ross, who found it near the Boothia Peninsula in the Canadian Arctic.

By the 1940s, the magnetic north had shifted approximately 250 miles (400 kilometers) northwest from where it was in 1831. In 1948, it arrived at Prince Wales Island, and by the year 2000, it had moved away from the Canadian coastline.

Currently, it is heading toward Siberia, Russia, at a speed of about 55 kilometers (34 miles) per year, which is significantly faster than the typical annual movement.

One that began in the Arctic nearly two centuries ago and continues today, tracking this movement has never been more important. That’s where the World Magnetic Model comes into the picture.

World Magnetic Model (WMM)

The World Magnetic Model is jointly developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA), the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), and the British Geological Survey (BGS). It is also a collaborative product of the United States’ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the United Kingdom’s Defence Geographic Centre (DGC).

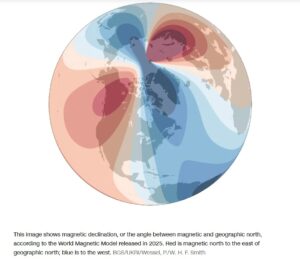

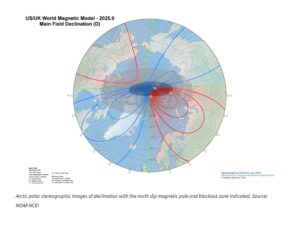

Considered as the fundamental instrument for mapping variations in Earth’s magnetic field, the World Magnetic Model (WMM) is a spherical harmonic representation upon which the entire global navigation infrastructure fundamentally relies. This model documents the established position of magnetic north and forecasts its future movements based on observed trajectories over recent years.

The newly released version of World Magnetic Model 2025 (WMM2025) delivers enhanced navigational data accuracy for all military and civilian aircraft, maritime vessels, submarines, and GPS-enabled devices.

Given its critical role in navigation, the model undergoes updates at a minimum interval of every five years. Notably, alongside WMM2025, the World Magnetic Model High Resolution (WMMHR2025 was introduced, offering improved spatial resolution that translates into increased directional precision.

Timely adoption of the most current magnetic north models is imperative, as delays in updating lead to progressively larger errors. To demonstrate this idea, imagine trying to travel from Chicago to New York City with an old map, but ending up in Philadelphia instead, which is more than 90 miles away from your intended destination.

A research scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information claimed, “The way the model is built, our forecast is mostly an extrapolation given our current knowledge of the Earth’s magnetic field.”

Lately, however, it’s picked up speed in a way that’s forcing scientists to rethink what they know.

Future Shifts, Reversals, and Their Impact

Are we overdue for a magnetic pole flip? Historically, the last major complete magnetic pole flip occurred roughly 750,000–780,000 years ago.

Scientists still don’t fully understand why geomagnetic reversals happen—or when the next one might occur. Magnetic north could continue drifting at its current pace, slow down, or even accelerate. While a complete reversal typically takes thousands of years and is thought to occur about once every million years, there’s no precise schedule.

Many species—such as aquatic animals, butterflies, and migratory birds—rely on Earth’s magnetic field for navigation and would face significant challenges during a reversal. Human technology wouldn’t escape unscathed either: radio communications or navigation systems could be severely disrupted. GPS, aviation, and undersea cables would fail to support.

Although a flip isn’t expected in the immediate future, its eventual occurrence and its impact would be global.

Be the first to comment