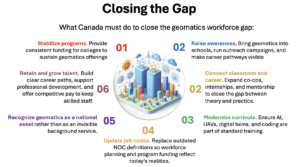

Program closures, retiring workforce, and outdated policies are converging into a workforce crisis that could derail Canada’s infrastructure ambitions.

Canada’s infrastructure ambition has never been clearer — but the workforce behind it is fraying fast. A 2025 report by the Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University, Infrastructure Trends and Innovations: Implications for Employment and Skills in Canada, warned that construction and infrastructure would require not just greater numbers of workers, but new competencies: digital skills, AI-readiness, data literacy, and automation.

That warning isn’t theoretical in the geomatics industry anymore. As governments roll out billions in infrastructure investment, the people who measure, map, design, and model those projects are being squeezed. Licensed surveyors are retiring with few replacements; CAD and BIM specialists are in short supply; remote sensing and GIS developers are hard to recruit; and graduates arrive under-prepared for the digital and AI-driven tools now standard on job sites.

Industry leaders, whose projects depend on both speed and precision, are already seeing cracks in their ability to respond. The threat is simple: Canada can’t keep building if it can’t staff the builds.

Industry Under Pressure

The Diversity Institute report put it plainly: Canada’s infrastructure sector faces a “looming labour shortfall” and will need new competencies in “digital skills, Building Information Modeling (BIM), robotics, automation, green building, prefabrication, and modular construction.” It also warned that Canadian firms lag in adopting these technologies, with productivity already suffering.

And it’s not just one report. The Future Skills Centre’s Skills Algorithm report further confirms that employers are not only seeking baseline digital fluency (data handling, platform tools) but also advanced skills (coding, automation, database management). Meanwhile, an earlier FSC-CCF survey funded by the Government of Canada shows that 80% of businesses say digital skills are needed, yet two-thirds struggle to hire people who actually have them.

Industry leaders are seeing the effects directly. Bryan Waller, Director of the National EnviroDigitization Program at WSP, one of the largest engineering consultancies in the country, says the strain is visible across the sector. Specialized roles such as digital project management, geospatial intelligence, and advanced construction techniques are increasingly difficult to fill. The shortage is most noticeable among mid-career professionals — the very group expected to lead project teams through today’s infrastructure surge.

Midwest Surveys COO Alex Penner says workforce shortages are broad-based, hitting surveyors, GIS technicians, field crews, and project managers alike. He sees the root problem as visibility: too few young people understand what a career in geomatics entails, making it harder to attract new entrants into the profession.

For GeoVerra CEO Mitch Ettinger, the strain is especially acute in hiring trained, experienced field personnel, particularly in major centres where competition for talent is highest. GeoVerra has responded by expanding internal training and professional development, while also offering above-industry wages to attract and retain experienced staff.

To counter the shortage, firms more broadly are leaning on a mix of outreach and internal investment. They are partnering with schools to raise awareness of geomatics careers, supporting events that introduce students to the field, and strengthening internal training and professional development to retain staff. Many are also offering above-industry wages to stay competitive in attracting experienced personnel.

HR professionals are also seeing the same pattern in the talent market. Valeria Sotelo, Talent Acquisition Specialist at Esri Canada, describes hiring as “moderately difficult.” Analysts and consultants are relatively easy to find, but GIS Developers, Senior Consultants, and utility-focused technical roles are consistently tough to fill. Geographic constraints make roles in places like Ottawa even more challenging.

Preliminary results from the GoGeomatics national workforce survey align with what these voices describe. With over 150 responses so far, the survey shows land surveyors, CAD specialists, crew leads, and remote sensing experts as the hardest to recruit. GIS analysts, by contrast, are among the easiest.

The takeaway is not that industry cannot deliver, but that it is doing so under conditions that are brittle and unsustainable.

Cutting the Pipeline

Across Canada, geomatics programs are collapsing. Administrators look at shrinking enrolment, see no path to growth, and quietly cut courses. On paper, it’s a financial decision. In reality, it is dismantling the supply chain for one of the country’s most critical professions.

The reasons run deep. Domestic awareness of geomatics is almost nonexistent — few high school students, parents, or guidance counsellors know the career even exists. Programs that once filled seats with international students are seeing those numbers decline as global competition intensifies. Funding models reward enrolment, not national need, which makes small, technical programs an easy target when budgets tighten.

The result: a slow, nationwide shuttering of the education pipeline just as demand for geomatics explodes.

Educators describe the damage in blunt terms. Patrick Whitehead, Chair of Surveying and Geospatial Engineering Technology at Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT), warns: “We’re losing talent we can’t afford to lose. Once a program is closed, it’s almost impossible to bring it back.”

At Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT), veteran instructor Carina Butterworth points to the awareness gap: “If people don’t even know about the career, they won’t choose the program. That’s why we’re not filling classes. We’re in danger of a lost generation of surveyors.”

At Nova Scotia Community College, Dr Tim Webster has seen the imbalance firsthand. GIS analysis still attracts students, but fewer are choosing surveying and field data collection — even though that’s where demand is strongest.

Industry leaders echo the frustration. Will Cadell, CEO of Sparkgeo, calls the situation “bizarre.” On one hand, industry says it doesn’t have enough people; on the other, programs are closing for lack of demand — and layered on top of that is hype that AI will take jobs away. “All three of those can’t be true at the same time,” he says.

If shortages are real, programs should expand. If AI is reshaping roles, training pathways should evolve, not disappear.

According to industry veteran Peter Srajer, enrolment is faltering because young people and their parents don’t see a clear career path in geomatics. “Everybody knows what a civil engineer does. Nobody knows what a geomatics engineer is,” says Srajer, himself a geomatics engineer.

The GoGeomatics workforce survey underscores the urgency. Nearly 80% of respondents so far say program closures will directly affect Canada’s ability to deliver infrastructure. Lack of awareness was the most cited reason.

Preliminary though they are, the findings point to a fundamental contradiction: Canada is investing billions in infrastructure while dismantling the very programs that train the people to build it.

Surveyors in Short Supply

If cracks are visible across geomatics, they are deepest in surveying. Every major project requires a licensed surveyor’s signature, but the pool of professionals who can provide it is shrinking.

The structural reasons are clear. Licensing takes years of study, articling, and exams — a path that deters many would-be entrants. Demographics make it worse: a large share of surveyors are approaching retirement, and too few younger professionals are stepping in. Add to that an image problem — surveying is seen as obscure or outdated — and recruitment has become an uphill battle.

Chris De Haan, President of the Association of Canada Lands Surveyors, has warned that federal licensure faces the same cliff as the provinces. “The shortage of new engineers and surveyors is expected to continue growing, and it’s the younger generation that we’ll depend on,” he says.

Infrastructure worth billions depends on a pool that is aging out.

Brian Munday, Executive Director of the Alberta Land Surveyors’ Association, points to systemic challenges that go beyond demographics. Because surveying programs are small and require costly labs and equipment, current government funding models often leave them vulnerable. Entry has also become harder for students from rural communities who must relocate and pay high costs to study in cities. Historically, Alberta has relied on boom-time influxes of surveyors to meet demand, but Munday warns that depending on those cycles risks bottlenecks just as major infrastructure investment ramps up.

From the classroom, SAIT’s Butterworth thinks the real danger isn’t only in getting students through the door, but in keeping them there. Too many drop out before completing programs, and those who do graduate often prefer GIS or office-based roles over the fieldwork that industry most needs. That imbalance risks leaving Canada without enough qualified surveyors at precisely the moment demand is climbing.

Butterworth adds that the pathways into surveying themselves can be a deterrent. The process is long, rigid, and expensive, especially for students weighing career options against other professions with clearer entry points. Srajer agrees, calling the licensing process “too arduous and rigid” and warning that it deters smart young people who might otherwise enter the field.

The surveyor shortage is not unique to Canada. Bryn Fosburgh, Vice President of Trimble, stresses that the most acute gap is in mid-career professionals with registration — the group carrying much of the sector’s expertise. Many are nearing retirement and not easily replaced. “When this group exits, the loss will be profound,” Fosburgh maintains, adding that the challenge is global, not just Canadian.

The GoGeomatics survey reflects the urgency. Respondents ranked surveyors as the hardest role to fill across the entire geomatics sector, well ahead of analysts or office-based positions. The reasons are clear: it takes years of education, articling, and licensing to qualify, and demographics are accelerating the crunch. Without urgent planning, the retirement cliff becomes a freefall.

Graduates Eager, But Unready

Even when students graduate, the transition into the workforce is tough. Employers consistently describe new hires as motivated but not ready to contribute. That lag costs companies money and projects time. Firms such as Midwest and GeoVerra have responded by expanding internal training, professional development, and mentorship to keep projects staffed. WSP has taken a broader approach — supplementing Canadian teams with global mobility programs to bring in skilled professionals from other regions, while also building partnerships with colleges and universities to better align training with industry demand.

But as demand rises, the burden of bridging the gap is increasingly falling on employers.

At Esri Canada, Sotelo sees it often: “They bring strong theoretical foundations, but they need structured onboarding to understand workflows, data standards, and client-facing project dynamics.”

In practice, this means weeks or months before a new graduate is billable.

Waller cautions that employers cannot train their way out of the crisis alone. “Proactive workforce planning and stronger partnerships with institutions will be essential to ensure graduates leave with the skills industry actually needs,” he says.

Educators see the same weaknesses. Butterworth argues that expanding co-ops, internships, and mentorships would give students the grounding they need. Webster adds GIS analysts graduate in good numbers, but practical, field-ready staff remain scarce.

The GoGeomatics survey findings underline the problem. Three-quarters of respondents called for more work-integrated learning, and two-thirds said curricula must be updated for technologies like AI, UAVs, and digital twins. These preliminary results match what employers already know: Canada doesn’t lack enthusiasm in the classroom, but it lacks pathways that turn that enthusiasm into value on day one.

Technology Running Ahead

Geomatics faces a widening gap between technology and skills. Even as companies struggle to staff field crews and train new graduates, the technology underpinning the sector is evolving faster than the workforce can keep up. Drones and digital twins are now standard on infrastructure projects, and AI-driven platforms are reshaping how spatial data is processed. Yet most graduates — and many mid-career professionals — have little hands-on experience with these tools.

Valeria Sotelo puts it bluntly: “Most new hires and mid-career professionals need training to effectively use AI-based tools. Hands-on experience with automation and geospatial ML frameworks is not yet widespread.”

Cheryl Trent, Executive Director of Data Services at WSP, noted that the gaps are especially sharp in digital project management, geospatial intelligence, and advanced construction techniques. “The shortages are particularly acute in defence and northern projects,” she said, where demand is rising fastest.

Penner of MidWest echoes the concern, cautioning that while innovation is promising, it must not come at the expense of professional oversight.

Cadell argues the sector is moving toward “GIS without a GUI,” where spatial analysis happens in scripts and workflows rather than traditional desktop platforms. “The principle of geographic thinking doesn’t change, but programs need to teach students to code, integrate diverse data, and work in Python notebooks if they are to stay relevant.”

Educators see the same lag. Carina Butterworth warns that without curriculum reform, students will keep graduating with outdated skill sets.

Labour market data confirms the mismatch. The Future Skills Centre found that 80% of Canadian businesses need more workers with digital skills, yet many struggle to hire them. Employers increasingly want coding, automation, and data workflow capabilities — competencies still rare in most geomatics programs.

The GoGeomatics workforce survey confirms the consensus: 40% of professionals believe coding and programming should be standard in geomatics programs, while 65% call for explicit coverage of AI, UAVs, and digital twins.

Bryn Fosburgh strikes a balance: “This next generation is special. They’re entrepreneurial, eager to learn, and have the chance to transform the industry. But let’s be honest — none of us are fully prepared for the pace of AI.”

Unless Canada bridges this technology gap, it risks falling further behind, even as geospatial tools become more central to infrastructure delivery.

Government Still Blind

The loudest frustration is aimed at the government. In the GoGeomatics workforce survey, 78% of respondents said federal and provincial policies don’t reflect the sector’s education and training needs.

The clearest example is the National Occupation Classification (NOC) codes. As we argued in an earlier article, Canada’s Blind Spot, the federal government still defines geomatics with vocabulary written more than twenty years ago — before drones, AI, or digital twins were part of the profession. These outdated codes aren’t just paperwork; they shape immigration, funding, and workforce planning. When the government uses obsolete definitions, it is effectively planning for a workforce that no longer exists, while ignoring the roles industry urgently needs.

“The job I have now didn’t exist when I was in university. Jobs change. They always have. But our workforce planning systems haven’t caught up,” says Cadell. If program approvals and funding continue to be tied to outdated codes, he warned, Canada is “setting itself up for failure.”

WSP’s Trent adds that the challenge is compounded by siloed delivery models. Greater collaboration across geomatics, engineering, and construction, she said, will be critical — but only if supported by early alignment on project vision, shared digital standards, and a stronger commitment to continuous learning.

The effects of this misclassification are already visible. Job Bank Canada’s most recent forecasts show a “moderate” outlook for GIS technicians and remote sensing technologists, and only slightly stronger demand for land surveyors.

Yet employers across the country report the opposite: urgent shortages in precisely these roles. Worse, many of the most dynamic positions in the sector — geospatial developers, UAV operators, digital twin specialists, hydrospatial analysts, and geospatial AI specialists — don’t exist in official labour market data at all.

This blind spot has consequences. Programs that should be expanding are being cut, because government funding models rely on enrolment numbers and official outlooks that fail to capture reality.

To be fair, Ottawa has acknowledged the importance of digital talent more broadly. The federal government’s Digital Talent Strategy 2023–24 Year in Review highlights efforts to attract, develop, and retain skills in software, data, and cybersecurity for public service transformation.

Yet geomatics is absent from that framework, despite being fundamental to infrastructure delivery. Canada recognizes digital, but still fails to see the people who measure, model, and map the foundations of every project.

Project Delivery at Risk

Infrastructure projects don’t come with unlimited time. Political cycles and contractual deadlines mean that work that once allowed years for mobilization now expects full teams within months. That compresses every weakness in the workforce. Mobilizing hundreds of professionals across provinces is difficult enough; doing so while mid-career staff retire, graduates still need training, and the field season is short, turns delivery into a constant balancing act.

Industry leaders see the cracks forming. Mitch Ettinger warns that compressed delivery schedules are exposing just how thin capacity has become: “We’re ready, but timelines will be the real test.”

Peter Srajer adds that the problem is compounded by brain drain: “Canadian engineers and surveyors are being recruited aggressively by U.S. companies who offer higher pay and faster career paths, pulling experienced professionals out of the system just when they are needed most.”

The GoGeomatics survey reflects near-unanimous concern. Respondents overwhelmingly agreed that program closures, retirements, and skill gaps will derail Canada’s infrastructure ambitions unless addressed urgently.

This is not a side issue. It is the foundation on which every promise of housing, transit, and modernization rests. Without the workforce, billions in spending will translate into delays, overruns, and missed opportunities.

Note: Many of these workforce and education challenges will be front and center at the GoGeomatics Expo 2025 in Calgary, November 3–5. A special C-Suite panel, From the C-Suite: Navigating the Future of Canada’s Geomatics Sector, will address the path ahead, alongside dedicated programs on workforce development and education. If you haven’t registered yet, buy your tickets now.

Be the first to comment