From the Ground Up: Karina Delcourt discusses the relationship between reality capture and construction

As entrenched as Karina Delcourt is in her belief in the benefits of reality capture (RC), it can’t be easy sometimes to be a tech lover in the Canadian construction industry, a market that has been slow to adopt RC technology and integrate 3D models into their processes. Despite the proven efficiencies, productivity and cost savings of 3D technology, many construction companies are still entrenched in their conventional methods. That is not the case with ETRO Construction (ETRO) in Vancouver, Canada, a general contractor known for progression and innovation. As Strategic Initiatives Manager at ETRO, Delcourt not only gets to apply BIM, virtual design construction (VDC), and digital twins to ease and improve construction projects, she has a window into where RC is making inroads, where it’s stalling and where it’s not even on the map. Geospatial Journalist Mary Jo Wagner caught up with her at the recent GoGeomatics Expo to discuss why the technology is still in its infancy in construction, why there’s disillusionment, why you need to start at the end to create the most informed beginning, and why significant change needs to start with municipalities.

MJW: When you joined ETRO in July 2022, what was the company’s digital footprint like? Was it already an avid user of reality capture (RC) data and technology and software for VDC?

KD: Since its founding, ETRO has been a very digital-first company. There was a previous director of innovation and tech who set the foundation of what I work on today. There were a lot of initiatives around VDC and they were already using RC data and technology. And now we’ve been pushing 3D technology and data to make it more impactful in the field. When I started they were very good at using it in pre-production and planning and now we’re going through some test cases so we can also use the tech during construction.

For example, we have one Vancouver project that is weekly using RC and BIM comparisons. It’s a very dynamic project with many specialty installations and a lot of coordination that is extremely demanding so we have a full-time VDC manager on that project. He takes in all of the information from the field teams, manages it and analyzes it, and then supports the field team by planning their next week’s work every single week. It’s come a long way and we’re hoping we can roll this approach out wider next year.

More with less

MJW: How have advancements in BIM, VDC and digital twins helped ETRO succeed in executing projects with discipline and less people, given the labor shortages in the construction industry?

KD: They’ve enabled us to take on more complex projects a lot faster than a company of our tenure would typically take on. One of our recent projects that we’re most proud of is in Vancouver at 411 Railway. It was a brand new commercial ground-up build, and it’s built as two buildings with these timber frame bridges in between them. It’s all mass timber with the electrical roughed into the bridges themselves. We planned not only the design and construction of those bridges with our timber supplier and contractors, but the installation of them was logistically planned out with our VDC team using BIM. That was a very unique feature of the project and without those tech advancements would have been far more difficult to achieve. It would have been a lot of manual processes especially when you’re talking about constructing two buildings and connecting them with pre-fabricated bridges that would be flown in and placed by a crane. Unless you’re planning in 3D and 4D, those things are extremely difficult to anticipate. By using those digital processes we were able to successfully install those bridges and have a beautiful building.

The timber frame bridges connecting the two buildings at 411 Railway in Vancouver.

Education can lead to sophistication

MJW: Looking at the industry as a whole, the use of BIM, VDC and digital twins has been growing, but it’s been slow growth, particularly with digital twins. What do you think are the barriers to more widespread adoption?

KD: I was at a breakfast meeting recently and a UBC civil engineering professor touched on this by saying that the data involved in a true digital twin is massive. And we work with lots of data right now but to have a true digital twin data streaming of a building is an order of magnitude larger. And our computing power just isn’t there to handle it as a true digital twin. That’s one barrier. In terms of using digital twins during design construction, especially when it comes to projects where you’re coming into an existing structure or working alongside a base building contractor, the barrier to adoption is lower because you don’t have to stream the data constantly; you can do snapshots as you go. But that does still take sophistication on your team, not only to receive and process the data but also make use of it. At a previous employer, I was unfortunately involved in a project where we started down that digital path and the construction team was not sophisticated enough to use the data so they ended up causing more problems by not looking at it. So integrating technology requires everyone on the team to be a happy, willing player who understands how the tech will benefit them and the project. That educational piece is still missing. We need that education across the industry to foster that tech advancement.

MJW: For companies like yours, what’s driving them towards these tools? Is it predominantly an internal push or are you reacting to external influences like tech-savvy partners, developers or even consumers who understand the transformative benefits of the whole BIM-VDC-digital twin relationship?

KD: It’s both a reaction to the ever-evolving complexity of designs and buildings and the internal push to implement digital solutions in order to provide the best ways to deliver construction projects for our clients. At ETRO we just want to do better in general so we’re going to look at whatever is out there to see if it can help us and we’re never going to be that company with the “this is the way we’ve always done it” approach. That’s not our culture. So internally, we push ourselves as well. And we are finding more and more owners who are aware of RC technology and having a more sophisticated understanding that if you have a construction company that uses this technology, they’re far more likely to be successful than someone who’s using traditional methods. It’s becoming a difference maker in our market.

I’ve used RC in the past with clients where they were skeptical of the design and we took them out to the site with a QR code and augmented reality (AR) software, and showed them the 3D design while standing in the empty space that they were going to be in. When they experienced it in that 3D first person they no longer had concerns. It’s just that their ability to read drawings wasn’t where we’d hoped it would be –– but you can’t expect clients to be able to read drawings like we do –– so tech like RC and AR are great communication tools.

The disillusionment affect

MJW: For all the proven benefits of BIM for the construction industry, you have noted that there has also been disillusionment with those same benefits and promises. Why is that?

KD: Part of it is the uniqueness of the Canadian market. BIM adoption in Canada seems to have been mostly pushed by designers and not construction companies. In the US, construction really pushes BIM and it’s less popular with designers. So there are two things here. One is I saw a recent LinkedIn post that I thought was extremely uninformed around BIM because it stated that BIM has added time and money to projects rather than reducing them. That’s not the technology’s fault. Part of that is as design timelines get shorter because permit timelines are so long, the designers are disillusioned with BIM because they can’t necessarily pump out designs as fast as they think they should be able to. The other side is the example I mentioned where we use RC and BIM and then the construction team isn’t sophisticated enough to carry it forward. In that case, the process lags because of a lack of skill. The BIM wasn’t at fault. It was because the BIM wasn’t used. So whenever there is a tool on site that you don’t use, you’re wasting money. If you have a jackhammer sitting there that’s not being used, that’s wasted money. And BIM is the same. If you don’t use it, that is the waste of money. It’s not that the process itself is going to increase the time or cost of your project. If you do it right, it’s going to save you hundreds of thousands of dollars. But if you choose not to do it then you don’t have anything to measure against to say how much you would have saved. And unfortunately, construction has had this history of not truly measuring ourselves so it’s easy to put on the blinders and say, No, I don’t need it because…. And that’s where the disillusionment comes in, and that’s where more education and training is needed for people.

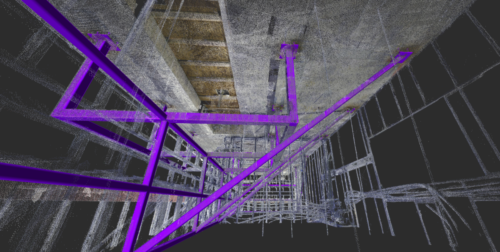

A structural steel as-built BIM.

From BIM to VDC to digital twins, seamlessly

MJW: As a BIM, VDC and digital twin all serve specific purposes in the construction project cycle, how can one create a seamless, interconnected exchange between all three and close data or application gaps?

KD: It really comes down to starting at the end first. You need to think about the digital twin first to inform the BIM. If there is a specific value to the owner or client on a project, that needs to be where you center your efforts in your VDC and BIM. There are certainly advantages to both a designer doing BIM and a general contractor doing BIM and VDC outside of what the owner needs for a digital twin so ultimately all three of these can stand alone. But you do need to understand what the owner’s value is and then work backwards from that because if you don’t, you run the risk of not having what the owner wants out of it. I’ve seen that far too many times in my career. You hand over the BIM at the end of the project and then it’s not what they wanted but they never told you what they wanted so how can you read their mind? I’m on a couple of task forces for building transformations and we’re trying to close that gap so that an entire plan can be knocked out, especially for large-scale projects where the owner is going to take that information and use if for facilities management or optimization planning in the future.

It’s unlikely that you’ll have an owner who has a sophisticated BIM team who knows all the detail they’ll need, but what you will have is an owner who is used to owning and operating buildings. So you need to understand what their model is of operating buildings, break that down into the required data to operate in such a manner, and then backwards extrapolate the construction and design that you need to do to achieve those ends. That’s how you create an integrated, seamless transfer of 3D data.

MJW: In some markets, infrastructure projects have over the past decade successfully been executed solely based on BIMs, eliminating the need for drawings. Do you think that will be a reality in the next few years, and is that a worthy goal?

KD: I think with enough time we’re headed there. But there are innovations already happening. The Iowa Department of Transportation, for example, only accepts BIM submissions for their roadworks. No drawings. You give them a BIM and they load the 3D model into their graders and they build the road without drawings. So that is absolutely happening and it’s a worthy goal. The issue is when you’re talking about infrastructure, specifically roads and highways, you’re talking about maybe two or three disciplines. When you’re talking about a building, 30 disciplines are not uncommon. So the order of magnitude of complexity is ten. So it’s not going to be easy. And some scopes will get there a lot faster. I think structurally we’re going to get there really quickly with structural models like those for fabrication that already happen through models. So why we’re taking those 3D models and outputting 600-page steel shop drawings is an inefficiency that doesn’t need to exist today. But, we do not have a correct model management method that would allow you to submit a model as a shop drawing as it were and have the engineer do the reviews there. So there are still gaps but they’re all solvable. We’re getting really close to the ability to show someone what paint colors are going to look like on walls because of gaming because in gaming you do house decorating all the time. So if you have one of the newer iPhones, they all have LiDAR lenses on them so you could scan your house, and we just need the app that closes the gap from the house decorating gaming to that LiDAR and you could paint walls whatever color and see them. I wouldn’t be surprised if a start-up is already trying that.

Does AI have a role?

MJW: Do you think AI will enhance the uptake and functionality of BIM, VDC, and digital twins for construction applications?

KD: AI in its current form in terms of large language models doesn’t really help us in this area. There is potential though. That same UBC professor mentioned that they’re creating AI algorithms to work with their scanners to independently identify the items that you’ve scanned. So, the AI engine can recognize that’s brick, that’s concrete, that’s steel.

Same for asset management with digital twins. We have a local start-up that is using AI mostly for text recognition but when, for example, you bring your steel in, each of your pieces is going to have a tag to it with material and installation attributes so because those standard attributes already exist in our database of drawings, when they scan that at installation, the model knows that’s a steel beam and it’s located at this spot. So it’s adding more intelligence to it to create a smarter digital twin. Right now, if you do a RC of your building, you need to go in and manually identify, this is an air handling unit, that’s a faucet. But the automation of that is coming. The other part that AI isn’t necessarily ready for and will come after this visual recognition is when you have your IoT sensors and streaming data from those devices linking the two. That’ll be in the next five years.

Modelling the future

MJW: ETRO is approaching its 10-year anniversary. Given the growth in people and technology in the company over that decade, where do you see the next ten years, for ETRO and the construction industry overall?

KD: I’m biased, but I think ETRO will be well-positioned. I think we’ll be at the center of something far cooler than just a traditional General Contractor model. I have a long wish list for where I’d like to see the technology take us. It’s almost 20 years in my career now where we’ve gone from the infancy of BIM to where we are now, and I think we’re going to see that same growth in the next ten. So when I started, BIM was seldom used. Only the most expensive designers and contractors had it. Now mid-market guys like us have it. And smaller shops also have it. I think in the next ten years we’re going to have every contractor specialty using BIM as a common practice. And I think we’ll be delivering digital twins in some form to owners.

The part that I am not sure of and the one I think is the biggest need for change in the next ten years is for our municipalities to accept BIM. The permitting process requiring 2D drawings is what kills us. And the constant resubmissions. One of my colleagues in the past brought in a model for a development permit and the city planner refused to put on the VR goggles and instead demanded additional renderings at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars. Whereas if that person had put on the VR goggles, every single rendering they could’ve imagined is already done. That is a huge barrier. Secondly, signing and sealing of models as an as-built asset for architects. How do we sign and seal a building model that could then go to the municipality? For drawing resubmissions, you spend two to three weeks redesigning and redoing the drawings and then you have to have your architect sign and seal them and put in a new permit application. You’re talking about three weeks to a month every time you have to deal with something that has to change. Whereas if we had an easy and quick way to sign and seal a model, those three weeks would likely go down to two or less.

With momentum building for reality capture technology in construction, Delcourt’s wish list for technology applications that will transform the industry may grow much shorter.