Dr. Vernon Singhroy is Canada’s one of the most distinguished Earth Observation scientists, known globally for his expertise in Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and remote sensing applications. Over his decades-long career, he has published more than 300 scientific papers, edited landmark publications, including Advanced Remote Sensing for Infrastructure Monitoring, and served as Principal investigator of RADARSAT 1 and 2, and Chief Scientist of the RADARSAT Constellation Mission of the Canadian Space Agency.

A professional engineer and former senior research scientist at the Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, Dr. Singhroy has advanced the use of radar interferometry for monitoring geohazards, energy infrastructure, and environmental change. His contributions span more than 35 countries, where he has helped build Earth Observation capacity through education, training, and international collaboration.

What makes SAR such a powerful tool in Earth Observation compared to other remote sensing techniques?

One of the biggest advantages of SAR is its ability to collect imagery in cloudy regions and at night. Optical sensors like Landsat or Planet imagery can’t do this, they’re limited by weather and daylight. But radar cuts through these conditions.

The second strength lies in the scientific side. Over the past ten years, we’ve really explored the value of polarimetric information in radar data. With it, we can monitor very specific things, soil moisture, crop types, tree structure, and more — based on how radar interacts with surfaces during different growth periods.

A third key area is data fusion. When you combine polarimetric radar with optical data, you unlock even more insight. And finally, there’s radar interferometry, tracking how the Earth’s surface moves down to centimeter-level motion. It’s used in infrastructure monitoring, for things like pipelines and highways, where subtle land shifts matter.

You mentioned radar interferometry as one of your core skills. How has it changed our ability to monitor environmental and climate-related changes in Canada and beyond?

Interferometry is essential when it comes to understanding how the land moves, whether it’s permafrost thawing in Canada, subsidence due to flooding, or structural stress in cities. And it’s not just academic — engineers use this data in practical ways.

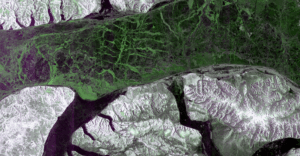

Radar is also critical in environmental monitoring. For instance, during floods, when the weather is bad, you can still get radar imagery to map land and water. It’s also used to track permafrost thaw, detect cutovers in tropical forests, and even measure ice melt. All of these are tied to climate change, and radar gives us a clearer, uninterrupted view.

From your experience, how can scientific research better influence policy and operational decision-making?

Most scientists, myself included, begin with pilot projects, we do the research, publish the papers. But that’s only the first step. When those pilots become operational, when they’re proven, repeatable, that’s when they start to influence policy.

A lot of what’s now routine in government, crop classification, soil moisture monitoring, ice detection, started as research. Over time, these methods matured and became best practices. That’s how science bridges into policy: through operational success.

You have worked in Canada, but you also support students and institutions in developing countries. What lessons have you learned about supporting global talent in geospatial science?

I am deeply committed to mentoring students around the world. I’ve taught at the International Space University, supervised PhD students in Canada, and regularly teach online courses in Guyana and across Africa. I have helped students in Nigeria, South Africa, India, and China, some of whom now lead space agencies.

To build global capacity, we have to invest in education. I often visit Guyana, give lectures, offer training, and help with master’s theses. Supporting developing countries isn’t just about exporting knowledge; it’s about lifting up future leaders who will drive their own regional innovations.

We have heard a lot at this conference about AI and big data. What’s your take on how these technologies are transforming satellite-based remote sensing?

AI is definitely becoming more central. But to be clear, remote sensing has used AI techniques for decades. Image classification? That’s machine learning. We just didn’t call it AI back then.

What’s changed is scale and capability. AI now helps us extract more information, faster, and with more precision. It’s an enabler, it makes satellite data more useful. Whether for mapping, monitoring, or detecting change, AI will continue to be a powerful part of remote sensing workflows. But it’s not new—it’s evolving.

Based on your journey, what advice would you give to emerging professionals from underrepresented regions looking to make a difference in remote sensing?

I don’t think I did anything special. I just loved what I did, and I worked hard at it. That, to me, is the real foundation of a meaningful career.

If you care about your work, stay honest, and keep learning, people will eventually recognize it. Recognition takes time, it doesn’t happen overnight.

And balance is important too. Be passionate, but don’t overdo it. Live a full life. If you enjoy science, keep doing it. If one day you don’t love it anymore, that’s okay too. Do something else you care about. In the end, it’s about making a meaningful contribution— and enjoying the journey along the way.

Be the first to comment