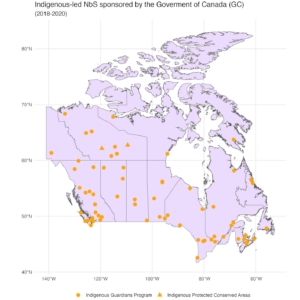

For decades, the conversation around conservation in Canada has been dominated by a “fortress” model—federal and provincial parks managed by central agencies. However, a landmark study released on January 6, 2026, by researchers at Concordia University is turning that map on its head.

The study provides rigorous, data-driven proof that Indigenous-led conservation efforts—specifically Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs)—are just as effective, and often more effective, at sequestering carbon and preserving biodiversity than traditional government-managed parks.

But for the geospatial community, the real story lies in how this was proven: through a sophisticated fusion of satellite remote sensing, carbon modeling, and spatial analysis.

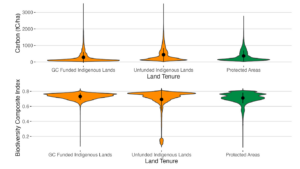

Analyzing the Impact: Climate and Biodiversity Outcomes

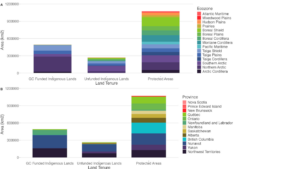

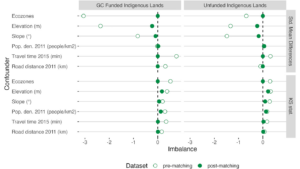

The Concordia research team used geospatial analysis to quantify exactly how much Indigenous stewardship contributes to national targets. Their analysis of Indigenous-led NbS revealed three critical findings:

- Lower Carbon Emissions: Indigenous-led areas saw significantly lower carbon loss between 2017 and 2020 compared to other protected regions. By preventing land transformation (such as logging or industrial fragmentation), these areas avoided “land-use emissions” that often plague non-Indigenous managed territories.

- Stable Biodiversity Indices: While global biodiversity is in decline, the researchers’ composite biodiversity index—which measures species richness, rarity, and ecological intactness—remained remarkably stable in Indigenous-managed lands.

- The “Funding Effect”: A key part of the analysis showed that federal funding for programs like the Indigenous Guardians ($125 million since 2017) acts as a force multiplier. When Indigenous communities have the financial resources to apply their traditional knowledge, the “avoided emissions” metrics improve almost immediately.

Mapping the “Irrecoverable Carbon”

Central to the study is the concept of “Irrecoverable Carbon.” This refers to carbon stored in peatlands, old-growth forests, and permafrost that, if released through development or wildfire, cannot be recovered by the year 2050—the global deadline for net-zero.

Researchers used national-scale geospatial datasets to compare carbon density and biodiversity indices across three types of land:

- Indigenous-managed lands (IPCAs).

- Federally/Provincially managed parks.

- Non-protected areas.

The results were geographically undeniable. In regions like Thaidene Nëné and Edéhzhíe in the Northwest Territories, the geospatial data showed that Indigenous stewardship consistently maintains higher “ecological intactness.” The maps reveal that IPCAs aren’t just lines on a paper; they are active, high-performing carbon sinks that outperform many conventional protected areas.

Remote Sensing: The Bridge Between Two Knowledge Systems

What makes this research a “Geospatial Story” is the technology used to bridge Western science with Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). To verify the health of these vast northern landscapes, scientists relied on:

- Sentinel-2 and Landsat Time Series: To monitor land-cover change and vegetation health over decades.

- LiDAR and GEDI (Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation): To measure the vertical structure of forests and calculate precise biomass and carbon storage.

- AI-Driven Predictive Modeling: To simulate how these lands will respond to climate shifts compared to commercially developed areas.

The Rise of the “Indigenous Guardian” GIS

The validation provided by satellites is only half the story. The study highlights the role of Indigenous Guardians—the “boots on the ground” who are increasingly using mobile GIS tools to monitor their territories.

By using ruggedized tablets and apps like KoboToolbox or ESRI’s Survey123, Guardians are collecting real-time field data on species migration, permafrost thaw, and water quality. When this ground-truth data is layered with satellite imagery, it creates a “Full-Stack” view of conservation that is more accurate than what any single agency could produce from an office in Ottawa.

A New Map for 2026

As Canada moves toward its “30 by 30” goal (protecting 30% of land and water by 2030), this research makes one thing clear: the most efficient path to climate resilience is through supporting Indigenous sovereignty.

For GIS professionals and geomatics experts, the takeaway is a shift in perspective. We are no longer just mapping “resources”; we are mapping the efficacy of stewardship. This study proves that when we give Indigenous communities the tools and the funding to manage their own lands, the data—quite literally—shines.

Be the first to comment