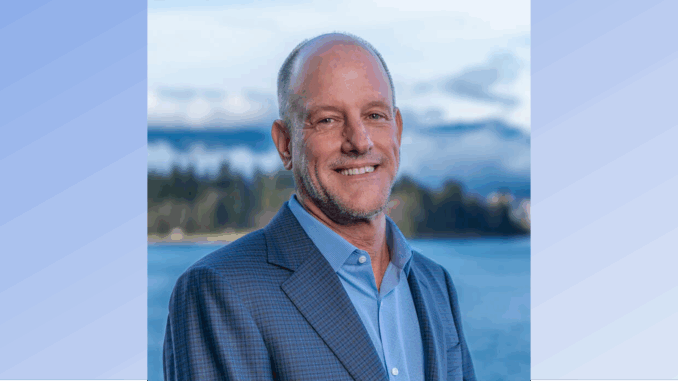

Fresh off the launch of the first satellite in its new constellation, EarthDaily Analytics is entering what CEO Don Osborne calls a transformative new phase — one that could see the Vancouver-based company become a global force in geospatial intelligence and environmental monitoring. But EarthDaily’s ambitions go beyond pixels from space. With a focus on broad-area change detection, spectral quality, and AI-ready data, the company is aiming to reshape how organizations across sectors — from agriculture and insurance to defense and climate — turn Earth observation into action.

In this wide-ranging conversation, Osborne discusses what sets the company’s constellation apart, how EarthDaily balances commercial growth with Canadian data sovereignty, and why the government’s procurement system still isn’t doing enough to back homegrown innovation.

Congratulations on the launch. What does this milestone mean for EarthDaily, and what’s next?

It’s a huge step. It takes forever to raise money and build satellites, so getting the first one up is a major milestone. Now we need to get the rest of the constellation up – that is what we are working on. When we designed the company, we deliberately avoided the common model of launching one satellite, proving it works, and then raising more money. That often results in your early satellites falling out of the sky before your full constellation is up.

Our mission is broad area change detection. The real value only kicks in once we have half — ideally all — of the satellites in orbit. That’s why we front-loaded our timeline. We found a great backer in Antarctica Capital, who supported the full vision. We also designed our satellites with a 10-year lifespan to avoid early decommissioning. The first satellite proves the system works and gives customers a taste of the data quality. By the time they have reviewed that first data, the rest of the constellation will be going up quickly.

What’s the full timeline for launch?

One more satellite goes up in October, and the rest in February. By early next year, our full value proposition will be operational.

You have called this the most advanced EO constellation ever built. What makes it different?

Most companies in EO today are chasing ultra-high resolution — 30 cm, sub-meter — because that’s what the defense sector traditionally pays for. But our view is that high resolution is only part of the story. What matters more, especially for commercial and analytical applications, is consistency, coverage, and spectral quality.

If you want to track change over time — especially in agriculture, forestry, or environmental monitoring — you need high revisit rates and repeatable conditions. Otherwise, your models break down. If you give an AI poor-quality or inconsistent data, you get false positives. Then you need humans to sort through those, and that kills your scalability.

We have taken a Sentinel-like approach, but with much higher revisit and full global coverage. Our satellites have 22 spectral bands — 11 aligned with Sentinel-2, and the others chosen specifically for things like soil moisture, atmospheric water vapor, and surface temperature. That allows us to do things that simply aren’t possible with RGB or even typical multispectral data.

We are not trying to replace the big guys, we are building something complementary. We want to be the broad-area, high-frequency layer that flags changes, so high-res assets can zoom in when needed.

Do you build your own satellites, or do you contract them out?

No, we don’t build the satellites ourselves. That’s not our business. Our strategy is to partner with best-in-class suppliers for hardware and focus our expertise on the ground segment, analytics, and customer delivery.

Our optical payload — which is really the crown jewel — is being built by ABB in Quebec. We have also worked with INO and Xiphos for critical subsystems. The satellite bus is supplied by Airbus, integration is handled by Loft Orbital, and launch is with SpaceX.

We manage the overall architecture, integration, and data pipeline. That includes our ground stations, cloud infrastructure, APIs, data fusion, and AI models. That’s where we differentiate. That’s where the value is.

That’s not going to change. We will leave satellite manufacturing to the specialists and stay focused on what we do best: turning data into insight.

EarthDaily already operates a platform that ingests data from multiple satellite constellations. How will data from your own new constellation be integrated into this platform?

Our platform today already supports multi-source data, including Sentinel, Landsat, and commercial providers. That’s important because a lot of customers have their own preferred data streams, and they want to see everything in one place.

Our platform today already supports multi-source data, including Sentinel, Landsat, and commercial providers. That’s important because a lot of customers have their own preferred data streams, and they want to see everything in one place.

Some of our customers are very technical — they want raw imagery, and they will run their own algorithms on it. For those users, we provide direct access through an Amazon S3 bucket. It’s fast, it’s scalable, and it gives them exactly what they need.

Others want to use our platform to explore areas of interest, filter and download relevant data, or even run change detection. We’ve built the tools to support that. We also support a BYOAI model — bring-your-own-algorithm — so clients can run their models on our infrastructure.

And then we have got a third category — customers who want us to do the heavy lifting. That’s where our acquisition of Descartes Labs comes in. We now offer full-stack analytics and insights, from raw data all the way to decision-ready intelligence. Some clients don’t want pixels — they want alerts, dashboards, forecasts. We support the full range.

What kinds of insights will EarthDaily’s new constellation unlock — and which sectors stand to benefit most from this data?

Let’s take insurance as an example. Most insurers today rely on static flood maps and historical models. They overlay those on policyholder data and estimate exposure. But we think that can become much more dynamic and even predictive.

With the new constellation, we can help model incoming flood events using real-time snowpack data, soil moisture, and other indicators. That allows insurers to better forecast their reserve requirements. More accurate projections mean more working capital and less capital locked away “just in case.”

And when it comes to parametric insurance, which pays out automatically when certain thresholds are met, this kind of real-time Earth observation is critical. It improves the viability of the product for both insurer and insured.

In the asset management world, we are seeing interest in combining geospatial risk with financial models. If you are a global asset owner, this kind of monitoring helps you understand where your assets are most exposed — whether to climate impacts, land degradation, or other environmental risks.

Then of course there is defense. Today, high-resolution satellites are tasked based on human intelligence — someone has to tell them where to look. But what if we could flip that? What if broad-area change detection could tell you where to look in the first place?

Take an example from northern South America. Drug traffickers sometimes mow down a strip of jungle to create a makeshift airstrip. By the time someone notices, the operation may be gone. But our system could flag that vegetation loss within a day or two — triggering a high-resolution satellite to verify the activity. That kind of cued surveillance drastically shortens response time.

We see a wide range of applications in insurance, defense, agriculture, mining, forestry, and climate response. The insight comes from seeing change as it happens, and being able to act on it quickly.

Is there a specific focus on Arctic monitoring, given Canada’s strategic interest?

Absolutely! Because of the way our constellation is designed, we will get much faster revisit rates over the Arctic than other parts of the world. Once our full system is operational, we will be capturing data over the Arctic multiple times a day, which gives us the ability to track physical movement almost in real time.

Think back to the Chinese balloon incident a few years ago that was floating through Canadian airspace. That kind of activity — slow-moving, high-altitude objects — is hard to spot, especially against a white background. But with our revisit frequency and spectral coverage, we could pick up those anomalies far more quickly.

It’s not just about balloons either. Any movement of vehicles, troops, or infrastructure in the North would stand out clearly. Our system would detect that within hours of it happening. That’s incredibly valuable for both civil and defense applications.

And it’s not just security. We also acquired SkyForest, a small Ottawa-based company, last February, which brings in strong capabilities around wildfire and forest monitoring. Those same models can be adapted for tundra and northern ecosystems, which are seeing climate-driven changes. We will be able to monitor vegetation shifts, permafrost degradation, and forest recovery across the Arctic. That’s a big opportunity — and one we are excited about.

So, what does EarthDaily’s go-to-market strategy look like now with the new constellation coming online? Are you targeting governments, enterprises, or resellers with this new data offering?

All of the above. We work with both civil and defense agencies, and with commercial customers in sectors like agriculture, mining, and insurance. Some want raw data, others want refined information. We are balanced across government and enterprise.

How has the response been from the Canadian government specifically? There’s a consensus that Canada’s procurement system is holding back domestic EO and space companies — particularly when it comes to the government acting as an anchor customer. What are the key structural issues behind this challenge?

I am cautiously optimistic. The increased defense budget signals a shift, and there’s definitely more conversation about buying Canadian goods and services — which is encouraging.

That said, I have been in this industry for 40 years, and I have consistently seen Canada fail to act as an anchor customer in the way other governments do. In many countries, governments step up and say, “You’ve got a great idea — we’ll be the first to buy it.” In Canada, that kind of early commitment is extremely difficult. Our procurement system doesn’t allow for pre-buying services or committing to purchases before something is operational — even if it’s just a year or two out. That needs to change.

To be clear, I am not saying governments shouldn’t buy physical assets — there are times when you need to own your ships or your submarines. But when it comes to space infrastructure, it makes a lot of sense to buy the data instead. Why not source the data from Canadian companies and help those businesses grow?

Buying services — not just hardware — helps companies raise funding and demonstrate traction. The earlier you get that kind of support, the easier it is to scale. So yes, I would like to see procurement policies evolve in a way that lets government stimulate and support Canadian EO firms at earlier stages.

As EO becomes more strategic globally, there’s growing concern around data sovereignty and access. How does EarthDaily’s constellation strengthen Canada’s ability to generate, manage, and control its own satellite data?

It’s a nuanced question. From a country’s perspective, data sovereignty often comes down to where your data is stored — and who controls access to it. A lot of cloud services are hosted in the U.S., and there’s growing apprehension about what happens if access is ever restricted or disrupted. So yes, there’s a strong move to ensure that data generated for Canadians — especially by or for government — is stored on Canadian soil. And I fully support that.

That said, we are a company focused on the global market. We are not building a satellite for Canada to own outright and operate. Our model is commercial, and we generate and distribute data to clients around the world. But when the Canadian government buys from us, that data is theirs. And we absolutely support hosting it on Canadian servers, if that is what is required. That is an important piece of sovereignty, and we understand the need for it.

Where things get more interesting is in what you do with the data — the AI and machine learning that turn raw imagery into insights.

What does long-term success look like for EarthDaily?

We want to be both a data company and a data intelligence company, and I think that distinction really matters. Today, if you are selling Earth Observation data, you are usually talking to someone with a background in data science. They need to understand spectral bands, radiometric quality, temporal cadence — all that technical stuff. But how many companies actually have a data scientist who knows how to work with EO imagery? Not many.

So that limits the size of the market for raw data. Meanwhile, there’s a much larger market of people who want to understand the world — to monitor crops, track floods, detect deforestation — but don’t have the tools or expertise to interpret EO data themselves. That’s where the real opportunity lies — delivering insights, not just imagery.

The EO industry historically has focused on selling images. But with machine learning, we can go beyond that. We can build mathematical models of the Earth’s surface and generate derived products — dynamic maps, forecasts, alerts — that are actually useful. And we can do it at scale.

What we really want to build is something like a large language model — a kind of ChatGPT for Earth observation. A system that lets users ask questions about what’s happening on the planet and get answers, not just pictures. That would open up Earth Observation to a much broader audience.

To me, that’s the long-term goal: to make EO data accessible, intuitive, and actionable. And we think broad area change detection is the right place to start.

Are you planning more acquisitions or expansion?

Yes. Our backers are growth-focused, and we see real opportunity to acquire smaller players — especially those who can differentiate with our data. That was part of the logic behind acquiring Descartes and SkyForest.

Be the first to comment