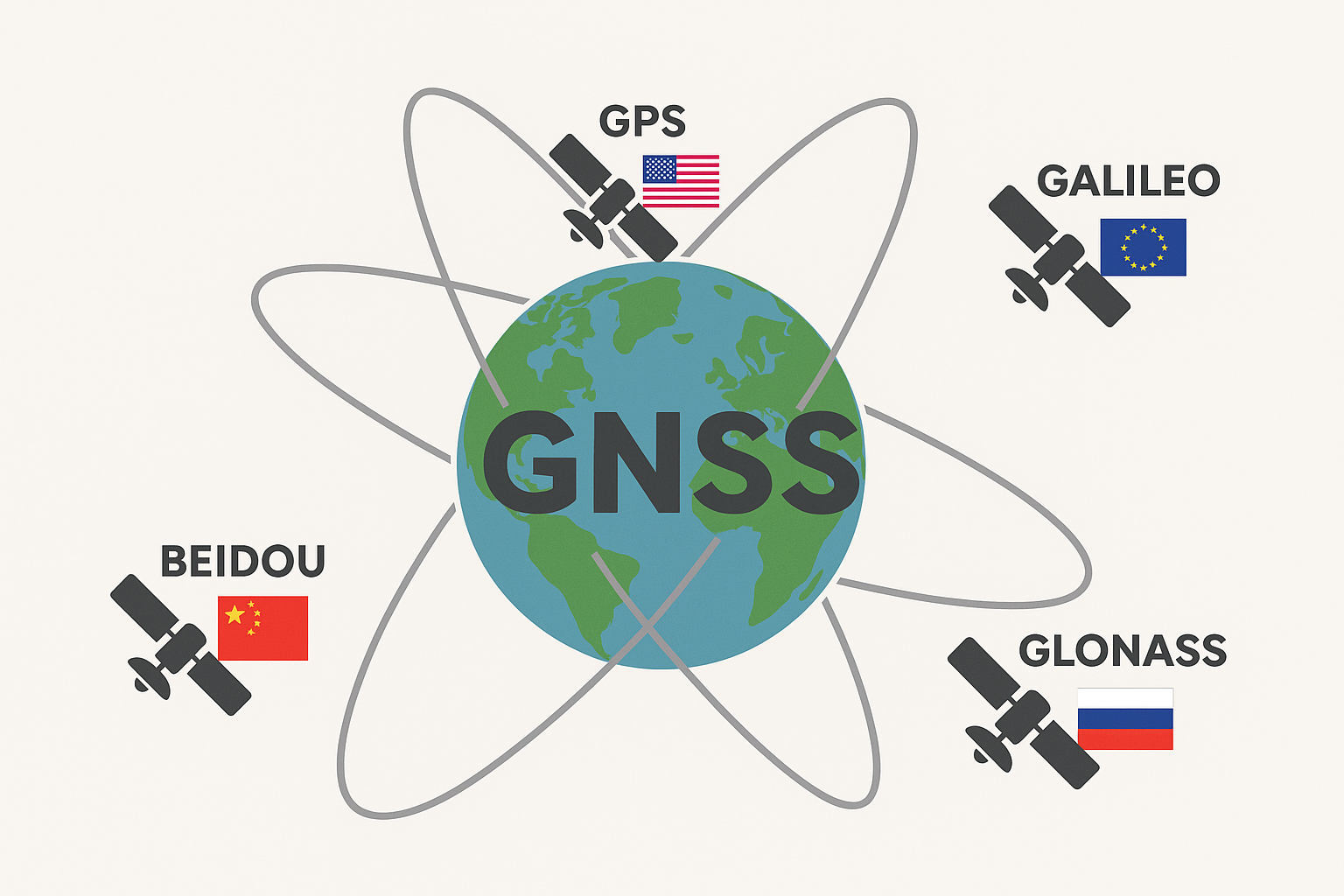

As the world becomes more unpredictable, the case for Canada’s self-reliance in critical infrastructure is stronger than ever. One of the biggest gaps is in satellite navigation. Positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) have become core to everything — from military operations to everyday business — but Canada is still reliant on foreign-controlled GNSS systems. And while they’re reliable, they don’t offer the sovereignty we need

Take at the Arctic, where Canada’s strategic interests are expanding. The region is difficult to navigate with current global systems, especially with the limitations GPS faces in high-latitude environments.

In the past, there was a concern that the U.S. could selectively “switch off” or degrade GPS signals in certain areas. But that’s not really the issue anymore. The U.S. removed Selective Availability back in 2000, and the system’s architecture has evolved to make regional denial both technically difficult and politically costly.

The real threat now comes from advancements in jamming and spoofing technologies. These days, electronic warfare systems can mess with GPS signals over large areas, making it useless without even touching the satellites.

For instance, since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, GPS signal interruptions caused inaccurate position readings along the Baltic region, creating safety risks for both civilian flights and military operations. Countries like Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, Sweden, and parts of Germany have all experienced GPS disruptions that have often been traced back to Russian transmitters. March 2024 witnessed one of the worst episodes of satellite navigation interference, which lasting 63 hours and affected more than 1,600 passenger planes.

The changing international order means technological independence is becoming a national security issue. For Canada, with the longest coastline in the world and vast Arctic territories,our navigation sovereignty is both a vulnerability and an opportunity.

Having a sovereign GNSS or even a regional system would give Canada the control it needs to navigate and manage resources — not just in the Arctic, but everywhere.

The Arctic Imperative

Canada’s Arctic and vast northern territories really show why we need to take control of our own navigation systems. GPS struggles in the extreme northern latitudes — its coverage just isn’t reliable where Canada needs it most.

The Russian GLONASS, on the other hand, has a clear advantage as it is designed with orbital patterns that make it better suited for the Arctic. As Russia expands its military presence in the region, it’s imperative for Canada to stay on top of the developments in the region.

The Northwest Passage has become a geopolitical flashpoint, as the melting Arctic has opened up these routes, and disputes over ownership of these waters have intensified. For Canada, reliable navigation throughout the passage is a critical element of sovereignty assertion.

Moreover, Canada’s current tense relationship with the U.S. — with rising tensions over trade, defense policies, and sovereignty issues — makes this situation even more complicated.

Need for a Resilient Navigation System

Research on Arctic navigation has shown the limitations of current GNSS systems in Canada’s northern regions, especially where GPS struggles to provide reliable coverage. To address this, Canada has taken action. The Department of National Defence (DND) is developing non-GPS-based systems to ensure military operations can continue if GPS is disrupted. This is part of a broader strategy to reduce reliance on foreign systems and boost operational resilience internally.

The Canadian Coast Guard has tested solutions like the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS), but they don’t meet the Arctic’s unique challenges. Beyond the Arctic, the Government of Canada is exploring alternative positioning systems as part of efforts to modernize transportation and communications infrastructure.

Positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services have today become vital for nearly every sector of the economy. It is especially important for planning purposes in Canada’s North, where some shorelines are constantly shifting. Adding more stations in the North and remote areas to improve positioning accuracy is a part of NRCan’s ongoing work.

The GNSS PNT Economic Value and Disruptions Cost Study evaluated the economic and competitive benefits of investing in precision GNSS-based PNT infrastructure. The study also looked at the impact of GNSS disruptions across sectors like agriculture, construction, energy, government, ICT, manufacturing, mining, and transportation (including road, marine, rail, air, and drone).

An independent or augmented system for Canada could help reduce vulnerabilities and open new commercial opportunities, as seen in countries with their own navigation systems.

ESA Ties and Limited Galileo Access

Despite Canada’s unique relationship with the European Space Agency (ESA), it still doesn’t have access to Galileo’s Public Regulated Service (PRS) — a secure, encrypted signal for military and government use. Like other non-EU countries, Canada can only use Galileo’s open signals for civilian and commercial purposes.

The UK’s experience with Galileo is a relevant example here. Post-Brexit, the UK lost access to Galileo’s PRS — the very system it had helped build. This loss of access highlights how geopolitical shifts can suddenly take away a country’s access to vital infrastructure.

Regional Navigation System a Viable Option?

The biggest challenge for Canada’s navigation independence is cost. A global system like GPS or Galileo would need a huge investment and years to build. But countries like India and Japan have shown that a smaller regional system can work just as well — without the massive price tag.

India’s NavIC covers the Indian subcontinent and surrounding regions, while Japan’s QZSS focuses on the Asia-Pacific. They are smaller in size but provide critical services where required.

Canada could create its own regional system focused on the mainland and the Arctic. A smaller constellation like NavIC and QZSS could give it more control while ensuring consistent service.

Interestingly, India’s decided to build its own navigation system after the U.S. switched off GPS during the Kargil War with Pakistan in 1999. This once again shows how changing political dynamics can influence countries to build sovereign infrastructure.

As Canada works towards a future of growing technological independence, the idea of Canada having its own GNSS is no longer just a nice-to-have — it’s a strategic necessity. The question isn’t “Should we?” anymore. It’s “How soon can we?”

Be the first to comment