Profound change could be ahead for surveying and geomatics, in the realm of quantum physics.

80-minute read: PDF

The term “quantum leap” often gets loosely thrown about in excitement over new technologies. This time though, the “quantum” part is literal. Specifically, “quantum sensing”. In this case, it is a leveraging of quantum physics, quantum mechanics, particle states and properties to improve foundational geodesy, sensors, systems, and methods for surveying and geomatics. For those unfamiliar with the term, “geomatics”, it is a relatively new term used to describe a broad range of disciplines encompassing surveying, mapping, reality capture, and spatial components of engineering, design, and construction.

The following geomatics applications, and related activities, could benefit from quantum sensing to some degree; directly or indirectly:

- Interferometry for navigation, and gravimetry (e.g., geodesy and underground mapping)

- Magnetometry for underground feature mapping, positioning, and navigation

- Accelerometers and gyros for navigation, monitoring, and solution stabilization

- Full spectrum antennas and encryption for communications

- Radar, lidar, and imaging

- Computing (e.g., enhanced cloud processing)

Research and development of quantum-enhanced sensors is booming, with some solutions already in the field. Yet this groundbreaking work, as well as the work of geomatics professionals, mostly goes unheralded. Both are doing work that society in general takes for granted. And when (not if) the scientists and developers deliver quantum magic for geomatics applications, their dedication and hard work might be not fully appreciated.

This article is not a deep dive into quantum physics, and experts might wince at the oversimplification of key concepts (my apologies). Instead, it is a non-technical overview for the rest of us.

Before we discuss elements of quantum physics, let’s look back at technological developments that have impacted surveying and geomatics, that provide perspective on what to expect from this nascent “quantum (sensing) leap.”

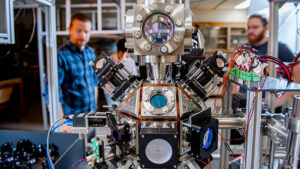

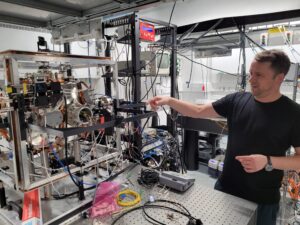

Right: Research and development for quantum sensing is successful in proving approaches and designs, with an aim to further develop into practical solutions for a broad range of applications. Some of these could benefit geomatics directly and indirectly. Pictured, the Quantum Sensing Ultracold Matter Lab at the University of New Brunswick. Source: UNB

Past Leaps

There has not been a singular development that completely revolutionized geomatics and surveying on the scale of what the development of marine chronometers did for navigation (solving longitude). For geomatics, it has been more of a series of incremental steps of varied significance. In some ways, quantum sensing might be just another incremental step, though rather mind-blowing in that it is leveraging science more profoundly than in the past.

A century ago, the world of analog surveying was rocked by a convergence of physics, precision optomechanics, and chemistry. The primary field instrument for surveying had been the transit or theodolite, the fundamentals of which had not evolved much for centuries. In 1920, along came a new wave of levels and theodolites that were more like scientific instruments. There were key advances: precise movements and reading mechanisms, more compact, lighter, and more reliable than legacy instruments.

These served as the basis for the electro-mechanical-optical instruments to follow. It should be noted that even with this “leap”, legacy-style instruments continued to also be produced (e.g., long-scoped transits), even until recent times. Big leaps are not necessarily ubiquitous.

While using light beams for ranging had been experimented with in the 1930s, it was not until 1947 that scientist Erik Bergstrand, with the Geographical Survey of Sweden, produced working prototypes that could transmit 10 million light pulses per second to a mirror over 30km distant. The results could be computed to the nearest millimeter. This forever changed surveying, but not immediately. It would take several decades before electronic distance measurement (EDM) lasers would become a common tool. By the 1970s, EDM would begin to be added to modern theodolite designs, evolving into total stations (TS), then motorized and software controlled as robotic total stations (RTS) by the 1990s.

Again, a series of incremental steps lead to such technologies becoming part of standard survey toolkits. The next steps would lead to mass data capture, or reality capture, which many practitioners and developers are treating as a distinct discipline. First developed in the 1960s, it was not until the 1980s that practical and portable terrestrial laser scanners, like the Cyrax introduced by Ben Kacyra, arrived. Now, such technologies (and variations) are everywhere: deployed on aircraft, drones, handhelds, backpacks, vehicles, boats, in some robotic total stations, on some GNSS rovers, and even packed around by autonomous robots. Together with digital photogrammetry, field capture has evolved to leverage the proximal richness of 3D point clouds and models, in contrast to the collection of discrete points and line stringing with legacy TS and RTS.

Left: One of Harrison’s marine chronometers, that revolutionized navigation in the early 18th century. On display at the Science Museum in Kensington London. The museum is only a short walk away from the Center for Cold Matter at Imperial College, where quantum navigation is being researched

Subsequent steps include developments on the downstream end, such as advances in computing to process, manage, and analyze the deluge of data from these, increasingly multi-sensor, reality capture devices. AI and cloud services are becoming key elements. With the advent of rapidly captured, rich 3D models, downstream applications for design and construction are experiencing leaps forward, fueled by improvements in data quality, completeness, and streamlined workflows.

If one had to name a (relatively) recent technology as having “revolutionized” geomatics, then GNSS would be a top candidate. Even if not used directly, the underlying geodesy, the reference framework for geomatics and geospatial applications, has been shaped by satellite navigation and advances in gravimetry. It made possible more recent waves of small drone mapping, mobile mapping, and more. While some might still distrust it for certain types of precision surveying tasks, there is no denying that it has impacted geomatics positively (if used appropriately of course).

Theorized over a century ago, certain technologies were later tested when the first artificial satellite orbited the Earth. Johns Hopkins University leveraged signals from Sputnik 1, essentially using it as the first navigation satellite. Later, the U.S. Navy Timation testbed system would leverage the quantum world of atomic clocks. These would become one of the fundamental elements of satellite navigation systems: GPS, the U.S. Navstar system launched in 1978. And other global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) that followed in subsequent decades.

Leaps forward are not always immediately embraced. For instance, in the early days of EDM, some crews were required to also use analog methods (e.g., tapes and chains) because the technologies were not yet trusted. And, when small mapping drones first appeared around 2010, the reaction from some in the surveying community (and the public in general) was not only skepticism but calls to “shoot em’ down”. Now, they’ve become indispensable for many surveying and mapping applications; photogrammetric, lidar, and combined solutions. These advances have brought increased productivity, efficiency, ease of use, and reliability. And often, instruments have become lighter, smaller, and relatively cheaper. I for one, fully appreciate that instruments have become more compact and lighter as I get older—I do not pine for the days of packing 30+ Kg of legacy GPS gear over hill and dale.

Quantum sensing implementations might not see as much pushback as some past tech leaps. Mostly because they seek to simply enhance current tools. Like imaging, lidar, magnetometry, gravimetry, and laterally, computing. There will be incremental advances, especially in improved sensitivity, the ability to work in more challenging environments, and new, enhanced, multi-sensor solutions and devices.

A Continuum

There are already examples of quantum sensing (principles and solutions) in use, as some have been, for decades. For example, medical instruments, like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electron microscopes, and (to some degree) single photo lidar. Then of course, there are atomic clocks, that provide the precise time that makes GPS/GNSS, and other applications possible. They also serve as the world’s clock for network computing, cellular systems, and more. More on the timing component of the quantum leap later. While some of these examples may not be employing some of the more recently leveraged elements of quantum physics, the development and evolution of these can give us an idea of what to expect when looking ahead.

Left: A quantum gravimeter was used for a year-long volcano study at Mt. Etna, Italy. Source: iXblue (Exail)

The deeper scientific details of how these amazing developments are coming together are not easily understood by those outside of scientific and academic circles. Sure, the rest of us might have been taught some fundamental concepts in school, about atoms and particles, but some pretty heady concepts inhabit a seemingly endless network of scientific rabbit holes we would get lost in. It is great though, to see quantum physics being taught in greater depth in schools nowadays.

In the early 20th century, quantum physics underwent a pivotal period of discovery and understanding. Great minds theorized about a fuzzy universe where certain elements of classical physics might not apply. For example, how “uncertainty” becomes one of the keys to a new frontier in scientific understanding. The rejection of many foundational elements of classical physics in the new quantum realm was controversial; Einstein himself insisted that much of classical physics did apply, while others vociferously disagreed (and were later proven to be on the right track). The debate between Albert Einstein and quantum physicist Niels Bohr, nearly a century ago, underscores just how much of a disruptive leap quantum physics represented.

Quantum physics concepts such as “superposition”, “entanglement”, “squeezing”, “cold matter”, and even “teleportation” (no, it is not related to futuristic dreams of beam transporters), would take volumes to cover, and a team of physicists to explain them. I am very grateful for the patience of several quantum scientists who explained just enough of the concepts to me to be able to convey the R&D going on for quantum solutions that could eventually benefit geomatics.

Quantum Sensing ≠ Quantum Computing

The focus of this article is quantum sensing, but first, we need to touch on (the much talked about) realm of quantum computing, and the differences between the two.

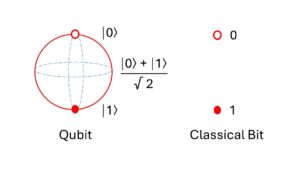

Right: While quantum computing and quantum sensing leverage some of the core elements of quantum physics, the benefits of quantum sensing is more likely to provide more immediate, and direct benefits for geomatics applications

Typically, when people hear about “quantum”, it is about quantum computing. There is excitement over the potential to improve cyber security, encryption, scientific analysis, etc. Crypto folks are giddy over the prospects (though likely under certain misconceptions). However, quantum sensing applications, that would seem dull and unexciting to those outside of specific fields, ironically might have a more immediate and direct impact on our lives—yet get little press.

When quantum computing becomes practical and affordable (a somewhat distant horizon), geomatics, et al will benefit—laterally. Though presently large, expensive, and power-hungry, such systems exist and are breaking a lot of otherwise hard wall rules for computing. However, it may be a long time before quantum computing is affordable and accessible to supercharge geomatics functions.

At some point though, there could be access to quantum computing-enhanced cloud services. Azure, AWS, and many other cloud services are already preparing for this. Then it could be practical to accelerate, for example, AI-enhanced post-processing, classification, and analysis for mass spatial data capture (e.g. lidar and imaging). AI has been in use, for example (via conventional computing platforms) for lidar point cloud classification. And has been for over 20 years (leveraging machine learning) but has recently advanced to neural network AI methods. Quantum computing would be a tremendous boost for such applications—and others that seem impractical at present.

“If you flip a coin, it represents two possibilities, heads (obverse) or tails (reverse) with equal probability,” said Venkateswaran Kasirajan, author of “Fundamentals of Quantum Computing – Theory and Practice” (a highly recommended introduction to the subject). This corresponds to the Boolean world of “true/false” or “on/off.” This is the “0-1” realm of traditional “bits,” the way conventional computing works. But, when you toss the coin, while it is still spinning in the air, it is in a superposition of being both head and tail at the same time. But when you catch the coin and look at it, it falls into one of – head or tail. Quantum computing works on this basic principle. “The qubit (an acronym for a quantum bit) is in a superposition state of being in two states — zero and one simultaneously with varying probabilities until measured. ”

“When we have a digital bit, it’s either zero or one at a given time,” said Kasirajan. “Now, you have two digital bits, for example. Together, they can represent either 0 or 1 or 2 or 3 at a given time.”

“But, in the quantum world, when we have two qubits, together they will be in all four states 0, 1, 2, 3 simultaneously with varying probabilities,” said Kasirajan. “This exponential capability of the quantum system provides for its computational advantage, which means complex problems can be represented easily with fewer numbers of qubits.”

Just how powerful are the qubits? According to the folks at Azure:

“Superposition allows quantum algorithms to process information in a fraction of the time it would take even the fastest classical systems to solve certain problems. The amount of information a qubit system can represent grows exponentially. Information that 500 qubits can easily represent would not be possible with even more than 2^500 [2 to the 500 power] classical bits. It would take a classical computer millions of years to find the prime factors of a 2,048-bit number. Qubits could perform the calculation in just minutes.”

Kasirajan ( left) is the co-founder and CTO of Quantum Rings, a firm that has developed quantum simulation, at scale; helping developers and researchers step forward into a quantum future using present resources. He has also researched quantum sensing technologies, such as enhanced magnetometry (e.g., for underground mapping)—more on this later. As for the respective timelines of widespread quantum computing and sensing, Kasirajan said, “Quantum sensing will be ready for commercial use much before noise-free quantum computing is available at utility scale.”

Cold Matter Fundamentals

Research in quantum physics and the development of practical applications for downstream technologies mostly fall under the realm of cold matter. Subject labs are often labeled as such. For example, there is a Center for Cold Matter at Imperial College, London (we explore their research in quantum navigation later). There is the Cold Atom Laboratory (CAL) aboard the International Space Station. Such labs number in the hundreds globally, in academic and scientific institutions, in defense R&D, and at commercial facilities.

In short, cold is cool. In 1997, the Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to Steven Chu, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, and William D. Phillips “for the development of methods to cool and trap atoms with laser light”. Such atomic manipulation was not entirely new, but the trio brought several developments to the field that spawned standard approaches in this newest wave of quantum R&D.

When you slow down atoms and particles, the various quantum states become practical to leverage. Cooling with lasers is the mechanism. When atoms absorb photons, energy is moved to a higher level, and a re-emitted photon drops to a lower energy level, in a direction opposite its motion. An atom loses more energy than it gains, slowing it down. This makes it slower (compared to the speed of light) than it started. And actually colder, in ranges where the Kelvin scale for temperature is used.

Right: Atoms are more like erratic blobs of unstable sub-atomic particles that can have wave-like behaviours, and not like the tidy diagrams of orbiting particles in school textbooks. However, this seeming chaos and varied states (normal and induced) provide boundless opportunities for quantum computing and sensing.

Two of the recurring quantum features of both computing and sensing approaches are superposition and entanglement. One of the most exciting and potentially beneficial aspects of the fields of quantum sensing and computing is that particles of atoms, even separated at a great distance can share a common state, act as if they are one, and even reflect changes. Though these concepts can be easily misunderstood, and sometimes wishful thinking overtakes narratives…

For example, there is a lot of buzz about the entanglement states appearing to be “transmitted” instantaneously. Entanglement is instantaneous across any distance. But information cannot flow at a rate faster than light. And, the process of measurement can make it moot, and to “transmit” any data, classical bits are still needed to make sense of the qubits. All of that aside, researchers and developers are doing great things with entanglement.

This cooling and slowing make it possible to employ optical traps using lasers for detecting variations in energy levels and quantum states. Cold atoms and particles, for instance, lend themselves well to alternate methods of interferometry.

While superconductors leverage cooling, this is only laterally related to such techniques as cold matter interferometry. Superconducting applies a simple cooling principle to reduce resistance and magnetic fields removed from a supercooled (as near to absolute zero as possible) conductor. It might be possible to have an electric current run through a superconducting loop indefinitely without a continued power input. Like quantum computing, superconductivity can benefit geomatics laterally.

However, the two key quantum techniques that will have a more direct impact are cold matter interferometry and Rydberg atoms (more on both later).

There’s an interesting bit of trivia related to this subject. Rubidium is used frequently for various cold matter applications. The scientists I spoke with noted that it’s a nice atom to work with for many complex reasons. However, in part, because laser technology that works nicely with its attributes is very well developed and has benefitted from unrelated development of lasers for even consumer applications. For example, CD players used to use a 785 nm (nanometer) laser which, coincidentally, is quite close to the rubidium cooling transition. Though such consumer lasers are not applied in serious quantum R&D, such lateral development helped bring costs down.

Techniques leveraging cold atoms, Rydberg atoms, superposition, entanglement, and more, make for much more sensitive sensors—the driver of the nascent quantum leap for geomatics and many more applications.

Cold Matter Interferometry

Light and signal interferometry have been applied to geomatics solutions for many decades. For example, a light beam can be split at the source, set on different paths to a target, and the differences are compared.

During a visit to the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Dr Saesun Kim (who was doing quantum research there at the time) explained quantum interferometry.

“It’s similar to classical interferometry, but instead of just light, we can use quantum particles like atoms,” said Kim. “In quantum mechanics, light and atoms both exhibit wave-like behavior. If you can control the conditions properly, you can achieve the same kind of interference effect as with a light interferometer.”

Dr Saesun Kim (left), during his research stint at Nasa-JPL

Kim further explained how this works, in general terms that non-scientists can appreciate: “We can use lasers to manipulate atoms and collect data. For example, we can use a laser to trap a group of atoms, creating what we call a cold atom. First, you prepare a glass vacuum cell where you can introduce atoms, such as rubidium, and then use the laser to hold these atoms in place, forming a dense cloud, like a ball of atoms”

“In light interferometry, a beam of light is directed into a beam splitter, which divides the light into two separate paths. These two beams travel along their paths and are later combined again. When they recombine, their overlapping waves create an interference pattern, which can reveal extremely small changes in the paths they take. In quantum interferometry, we do something similar with atoms. We start with an atomic cloud and use lasers to manipulate and split the atoms into two different quantum states or trajectories. Then, we use additional lasers to recombine the states and analyze the resulting interference pattern on the atom to extract information.”

JPL has multiple applications underway for quantum interferometry, several are focused on gravity. This will lead to advances in gravimetry in general, but one fascinating proposed application is using a super-sensitive gravimetry clock for space navigation.

Right: The Space Operations Mission Control at Nasa-JPL, Pasadena California. R&D in quantum sensing at JPL is focused on space application, though lateral benefits are certain

“At NASA, especially at JPL, the focus is, of course, on space missions,” said Kim. “The goal is to develop devices that can enhance space exploration. Early quantum applications at JPL included significant work on atomic clocks, which are foundational for other atomic sensors since precise timekeeping is critical for accurate measurements. For instance, our group has been working on advanced atomic clocks, such as those based on mercury ions. Recently, a deep-space atomic clock was launched that uses a mercury clock to measure time with unprecedented precision in space.”

Quantum interferometry can be particularly amazing for capturing even the subtlest acceleration, and as gravity is essential acceleration, it can make possible the various space mission gravimetric initiatives of JPL. Dr Kim, since his stint at JPL, is now working at Keysight, a company that originated from Hewlett-Packard and specializes in electronics and measurement technologies, where he contributes to quantum solutions for quantum computing.

R&D for quantum interferometric approaches is continuous. For example, recently a new technique was announced that could reduce impairment of measurements by atoms that behave in unintentional ways, especially at such high velocities. Some dub such atoms as “parasitic”. By using what is called “dichroic mirror pulses” for a Bragg deflection effect, a sort of “atomic traffic control” can be implemented. It acts like a “mirror” that allows desired atoms through and deflects the parasitic. Every incremental step for the technology will enable more end uses.

Excited Atom Fundamentals

The other key approach for quantum sensing involves Rydberg Atoms. Named for the Swedish physicist who developed the concept in the late 19th century. The formulae became the foundation for understanding, and later using, this particular type of excited atom.

Left: When excited by a laser, a photon or electron can enter a state where its orbit is expanded and isolated from others nearer the core. These isolated states enable many quantum sensing approaches

The mechanism is (and this is admittedly an over-simplification), that you can use a laser to excite an atom, and it can put a single electron in a higher “orbit”. Orbit is not exactly the right term, as the particles in an atom are not moving in nice uniform orbits (like the diagrams we were shown in school). It is more like a fuzzy cloud of particles, behaving more like waves. The electron does though move further out, far from the other particles. During the brief period, the electron is in this excited state, a lot can be gleaned from its behavior. A bonus is that it is possible to isolate the observations of these distant particles without interference from particles closer to the nucleus. Again, it is large populations of atoms that are excited and then interrogated.

Rydberg atoms are also used in various quantum computing applications, creating entangled states and enabling quantum gates. For geomatics applications, they can be ultra-sensitive to electromagnetic influences and are the foundation for various quantum magnetometry and radio frequency (quantum antenna) approaches… more on these later.

Quantum Magnetometry

Though magnetic compasses have become nearly obsolete (in light of newer technologies) for surveying and mapping, magnetometers are an invaluable tool for detecting metallic objects underground. The state of the art for conventional magnetometers though, has been relatively static, constrained by the limits of classical physics. Trusty handheld magnetometers, like popular Schonstedt devices, and others, allow surveyors to sweep a spot to find a survey mark or monument underground, and for utility locators to mark out (at least metallic) underground utilities.

Quantum magnetometers will certainly be more sensitive, might extend range (depth), and work in more soil types for underground feature mapping. But also, this ultra-sensitivity benefits many other applications, like for manufacturing and healthcare. There is a tremendous amount of R&D underway for the latter applications.

“There are two phenomena that happen here when there is an acceleration so let’s take a small glass cell that’s filled with say, rubidium atoms,” said Dr Kasirajan. “When you expand the atom cloud there with a laser, it is subjected to the acceleration of the of the environment. When you expose it to an environment, for example, you mount it on a truck, as the truck moves, this glass cell is subjected to all the translational and rotational movement of the truck. That causes the atoms inside the glass cell to interfere with itself.

“By using precisely calibrated lasers and optical instrumentation, we can measure how the atoms interfere with themselves. By measuring the interference pattern, we can precisely say what the linear and angular acceleration of that truck or the vehicle in which the sensor is mounted This is very, very precise.

Right: A quantum magnetometer might not look much different from classical magnetometers, such as those used by surveyors to detect metal control marks or utilities underground. This is a conceptual image (with a little help from AI).

“This is similar to what we can do with magnetometry. In the same principle, there is a small glass cell the size of a quarter of a fingernail, which is filled with an alkali metal gas like rubidium. We prime the atom with a control laser, which excites the electrons in the outer orbit, the electrons are ripped away from the nucleus into a faraway distance—in layman’s terms. When the electrons are moved far away from the nucleus or the rest of the electrons, it’s a totally unstable state for an electron because the electron has to get back to this original state. Its orbital motion will be altered by anything that’s happening in the environment like there is an electrical field or magnetic field. What happens is that this creates a Zeeman Effect in a magnetic field and a Stark Effect in an electrical field”.

Kasirajan explained how a relatively small quantum magnetometer could be built: a small glass cell, lasers to excite the atoms, and others to interrogate the excited cloud. Beyond these elements, the processing could be done on something as simple as a cell phone or tablet. Quantum magnetometers are likely to be the first wave of quantum sensing to become available directly for geomatics applications, like underground feature detection and mapping. Quantum gravimetry is another approach that could improve underground detection and mapping, but more on that later.

Quantum Magnetometry for Navigation

Another proposal, that is getting a lot of media attention, is to leverage enhanced magnetometry for navigation. The concept is that such devices, on satellites, aircraft, and on the ground could use “maps” of the earth’s magnetic field as a primary (or secondary ‘gut check’) reference for navigation. This had been touted as a potential alternative to GNSS and other navigation methods. There are now commercial systems on the market.

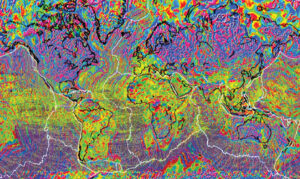

Left: The spatial reference for MagNav is not Earth core magnetism (that legacy compasses align to), but instead, crustal magnetic anomalies are mapped in high detail by many entities globally. For example, the World Digital Magnetic Anomaly Map (WDMAM). Khorhonen et al. (2007)

One approach to quantum magnetometry for navigation is to use enhanced quantum sensors to detect positions relative to Earth magnetism models. Precision could meet many coarse navigation, like for ships and aircraft, but could not replace GNSS for precise positioning.

There are advantages in that it does not require infrastructure, it can be more difficult to interfere with and can work in GNSS-denied environments. The challenges include the need to map the fields and to maintain the maps, as the fields are not completely static. There are other proposed approaches to this concept. One would simply measure the fields (even without a “map”). Like to determine and determine changes in trajectory, differentially from subsequent observations as the sensor moves. Precision though, is the issue for any quantum magnetometry navigation approach.

Geomatics applications fall under the realm of high-precision positioning. Quantum magnetometry navigation, like many of the other alternative navigation approaches, is coarse at best (tens of meters, hundreds of meters). This is great for navigating a ship or aircraft, but far too imprecise for geomatics applications. However, such approaches could greatly complement existing navigation and positioning approaches. For instance, an aircraft with a quantum magnetometer could act as a “canary in a coal mine” for its GNSS-centric primary solution, looking for large spatial changes that could indicate spoofing.

Right: Airborne and terrestrial (van) tests have been undertaken to gauge performance of the Ironstone Opal in a GNSS denied environment. Ground truth path was established, which Opal tracked tightly. In contrast strategic grade INS (a common GNSS backup) drifted significantly. Source: Q-CTRL

However, in the months since this article was first published, a fully funnctioning (not to mention affordable, low power consumption, and compact enough for broad adoption) was announced and put on the market. It outperforms conventional IMU in many real world nagivgation scenarios. Read my article on this development.

This system has since, been integrated into a drone platform. The potential for further integration into other systems, like mobile mapping, and even backpack SLAM systems, could have quite an impact on the reality capture sector.

Positioning, Navigation, and Timing

Quantum magnetometry navigation is a good segue into the much-examined topic of alternatives to, for example, GNSS-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT). The vulnerabilities of GNSS to spoofing, jamming, and interference is a very hot topic, that has spawned an industry seeking to develop alternate PNT, or AltPNT.

GNSS is ubiquitous, widely used for positioning, and navigation, and effectively serves as the world’s clock. The impact on, and value of GNSS for our modern world is tremendous. But so are anxieties about relying on it too much. The reality is that outside of conflict zones, the incidents of spoofing and jamming are extremely infrequent and isolated. Jamming, being highly illegal is almost unheard of outside of conflict zones, though there have been some deliberate incidents. And isolated instances of inadvertent interference, for instance, a naval vessel that turned on a system that would have otherwise only been used far out at sea, while in port.

The stakes are nevertheless high. Maritime spoofing and jamming occur, and backup systems, if not a total replacement for GNSS, have been developed. For instance eLoran. Additionally, precise time is crucial for so much of the world’s communications and network computing, so there are many backup time systems in place, or in development. Different countries have built networks of fiber optic linked time centers, and there are commercial providers of encrypted time sources, some delivered by low earth orbit satellites (LEO).

Some of the more vocal proponents and developers of AltPNT expend a lot of energy in focusing on the vulnerabilities of GNSS, with a few even suggesting halting GNSS development or even disbanding it in favor of their alternative solutions. However, as we will see, the alternatives are almost always yield lower precisions, so not suited as a direct replacement for GNSS positioning.

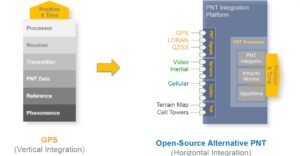

A more realistic school of thought is that it is not a zero-sum game. But instead, consider it as an “and” proposition, rather than an “or”. This was the conclusion from nearly a decade ago when the scientific and engineering teams at Aerospace Corp studied resilience approaches for PNT; this was dubbed “Project Sextant”.

Aerospace Corp was Chartered in 1960 during the peak of the space race. This independent, federally funded research and development center serves satellite and missile systems clients. Their government sponsor is the United States Air Force, and now the Space Force. The GPS Directorate is located directly across a busy boulevard from Aerospace Corp at the Los Angeles Air Force Base. Aerospace Corp had a prominent role in conceptualizing and developing elements of GPS.

During a visit to Aerospace Corp, Randy Villahermosa, principal director of research and development outlined the findings of Project Sextant: “We started with GPS and worked our way out to other technologies such as inertial, optical sensors, and opportunistic signals navigation. When we looked at all of these options, we concluded that we could not find a single drop-in replacement for GPS. We couldn’t find a single system that provided the same level of satisfaction, the same range of applications, and the same performance that was also not some variant of radio navigation from space. I think that was a critical affirmation of not only the general sentiment within the [PNT] community but also the conclusion of several key studies that had happened before Project Sextant.”

The recommendation was to develop multi-sensor/system PNT. This would include strengthening GNSS (which would not necessarily require new satellites), leveraging low earth orbit (LEO) navigation satellites, other broadcast systems (e.g. eLoran), opportunistic signals, inertial, magnetometry, image and lidar stabilization, and more. The result would be new types of field receivers for surveying, mapping, aircraft, ships, and autonomous vehicles.

Sorry for the detour into PNT. The point being made is that some quantum sensing solutions will fit very well into the vision of Project Sextant and other PNT resiliency initiatives.

Quantum Gravimetry

Precise gravity measurement is crucial for geomatics, especially since the advent of satellite-based positioning. Geoid separation models when applied to say, GNSS-observed ellipsoid heights yield orthometric elevations (e.g., often referred to as elevation above sea level, which is another nebulous subject).

Gravimetry has already taken a big leap, from the days of simple weights and springs, into digital and atomic. However, the fundamental principle is still there: differences in position over time squared equals acceleration—the effect of gravity is essentially an acceleration.

Gravity measurements to develop geoid models are often still performed with analog terrestrial (or “classical”) gravimeters. But increasingly, with digital vehicular, airborne, satellite, and even superconducting devices. Now, there are quantum gravimeters, and these enhancements will begin to yield even more highly refined geoids.

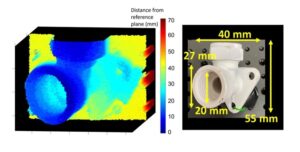

And there’s another geomatics application in store for quantum gravimeters: they can be leveraged for underground mapping, especially devices that can measure gradients in gravity. And the good news is that such devices already exist, in laboratories, but also as commercial products. Much of the research has an eye on both applications.

Dr Brynle Barrett (right), Associate Professor, Quantum Sensing Ultracold Matter Lab at the University of New Brunswick. Source: UNB

Quantum gravimeters were envisioned over half a century ago, and there have been many working devices. But only more recently have they hit the mainstream. iXblue (now Exail), a prominent French tech company that manufactures sensors and inertial navigation systems, released their Absolute Quantum Gravimeter (AQC) commercially. A key leader in their Quantum Sensors Division was Dr Brynle Barrett, who helped develop the world’s first three-axis quantum accelerometer while with iXblue. Dr Barrett is now heading up quantum sensing research at the University of New Brunswick (UNB). It should be noted that UNB is also home to geomatics and geodesy departments of international acclaim; it makes sense for geodetic-related quantum R&D to reside there as well. What Barrett and his team, as well as some other quantum gravimeter developers are doing is flipping the script on how several types of classical gravimeters work.

“The principle behind the matter-wave interferometer, that’s what the gravimeter is based on, is similar to that of an optical interferometer,” said Barrett. “In a matter-wave interferometer, the roles of matter and light are reversed. A classical free-fall gravimeter is based on an optical interferometer, where a coherent light source (a laser) is split into two different paths. One path hits a reflector that is in free fall, while the other path is stationary. When you recombine the light from these two paths, the light interferes and produces an interference pattern. These interference ‘fringes’, as we call them, have information about the difference in paths between the two arms of the interferometer. In the classical gravimeter, the fringes give a precise measurement of gravity because the path difference is proportional to gravity multiplied by time-squared.”

“The same thing is true in a matter-wave interferometer, except here we’re using light to split matter instead of matter to split light,” said Barrett. “We use laser light to first cool the atoms down to very low temperatures (a few micro-Kelvin), that’s our coherent matter source. At such low temperatures, atoms behave more like waves than like particles. We then use light pulses to split these ‘matter waves’ simultaneously along two different paths. These paths are made to cross each other at some time later and we recombine the matter waves with light to measure the interference fringe. If the interferometer is orientated vertically such that the atoms are in free fall, the phase shift of the fringes is again proportional to gravity multiplied by time-squared.”

The root of all this is position, time, and waves, not so different than from more conventional ranging and sensing approaches in geomatics but can be much more accurate and stable over long timescales. “The advantage of using a quantum gravimeter is that the atoms act as an internal calibration reference for everything: the time between light pulses, the frequency of the laser light, even the spacing of our “optical ruler” in the matter-wave interferometer”, said Barrett.

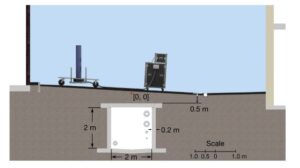

One interesting variant is stacking two gravimeters one atop another. “Because both proof masses (different cold atom clouds) are spatially separated, they fall at slightly different rates. Conceptually, knowing the separation, you can get the gradient of gravity by measuring the difference between the two rates and dividing by the separation,” said Barrett. “The beauty of a quantum gradiometer is that you don’t need to know the separation between the clouds at all. Using the same laser light pulses to realize both matter-wave interferometers simultaneously (along with some ingenuity) allows one to measure both gravity and the gradient of gravity, independent of the separation between atomic clouds.”

There have been many demonstrations of quantum gravimetry. They have been used to study volcanic activity, solid earth tides, ocean tide loading, airborne gravimetry in Iceland, and more. One study detected tunnels, and in another, some ancient Roman aqueduct sections, right under a public square that had previously not been mapped. Yet another study, that could eventually play out more broadly for geoid modeling (as used in geomatics) was a marine gravity survey.

Advantages over conventional instruments include not having moving parts that wear out and need to be recalibrated. Quantum gravimeters are as sensitive as classical gravimeters, on a shot-to-shot basis. Perhaps not quite as sensitive as certain superconducting gravimeters, but those are considered “relative” gravimeters because they are subject to large measurement drift. Barrett says that quantum devices have a distinct edge in repeatability, accuracy, and long-term stability.

Right: Quantum gravimeters have been used to detect tunnels, pockets of ground water, and historic structures. Source.

One drawback is size; these are not small systems. Typically, there is the gravimeter itself, often the size of a kitchen trash bin, and an auxiliary unit box that is connected via cables. I asked about the potential for a quantum gravimeter that could fit into the bottom of a survey pole, (something I’ve been dreaming out loud about for decades). “I don’t see it in the foreseeable future,” said Barrett. “I don’t see any way to say, reduce the total size by a factor of 100. Potentially factors of 2x and 4x could be possible. You need the control box, which contains all the power supplies and electronics, all the lasers, and all the RF components, and then there is the sensor head that consists of a metal vacuum system held around 10^-9 Torr with an active ion pump. It also needs some glass viewports with optics and photodetectors to inject laser light and measure atomic signals. Outside all that is a magnetic shield to isolate it from the magnetic environment. So, it’s a tremendous engineering challenge to make the entire system very small. Nevertheless, it is possible to shrink the sensor head significantly more for certain applications. This will likely come with some compromise in sensitivity.”

But even at this relatively large size, these will be amazing to model gravity for geodetic resources like geoid models. It could be used campaign style; say a city that is seeking to develop a 3D digital twin, developing its own geoid model to aid in the collection of the massive amount of reality capture needed. Or, at a project level. We may not ever have one in a survey rod, but these devices will contribute to advanced geomatics moving forward.

Such devices will also evolve in utility for underground mapping, but even in the present, these could potentially be brought in to provide additional data where conventional ground penetrating radar (GPR) has reached its limits (due to signal power limitations for safety). Quantum sensing is on track for enhancing radar, so GPR could be a lateral candidate for that.

Quantum Navigation

At the Science Museum in Kensington London, you can see a display of some of the amazing clocks built by John Harrison in the 1730s, the marine chronometers that were key in resolving longitude. This revolutionized navigation. A few short blocks away from the museum is Imperial College London (ICL), where their Center for Cold Matter has developed solutions to further the evolution of navigation.

How do you navigate in GNSS-denied environments, like underground or under the sea? External systems like beacons and transponders only work over short distances. You need something standalone, like inertial sensors (essentially gyroscopes). But even very good fiber optic gyroscopes (FOG), are still subject to drift, and without occasional external position sources to recalibrate them, work well only for a limited time. Quantum physics offers a way to extend the range of effectiveness, and these new devices are essentially quantum gyroscopes.

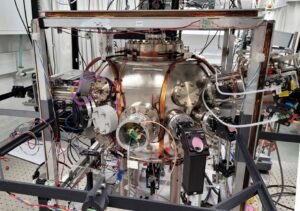

During a visit to ICL, Dr Joseph Cotter, Senior Research Fellow, Department of Physics, gave a quick tour of the lab and explained how such systems work. They operate in principle, like the interferometric accelerometers previously described.

Dr Joseph Cotter (left), Senior Research Fellow, Department of Physics, Imperial College London, explaining the components of one of their development quantum navigation systems

“Instead of using matter to reflect light, we use light to split, reflect, and combine matter,” said Cotter. “We can measure two horizontal accelerations, and we can measure a rotation about any axis. We’re using laser light to measure; it’s kind of like the light is a ruler. It measures the motion of the rubidium atoms. Gravity is going to be pulling these rubidium atoms down at the same time. So, we have to compensate for that.”

“The atom is described by a wave packet,” said Cotter. “Once we’ve split our wave packet, reflected it, and recombined it, we measure the atom, and when we measure it, that atom will be in one of those two states, and from that, we can infer what the dynamics of the system were.”

In the lab, there is a large spherical chamber, with fiber leads to cooling lasers on an adjacent table. Part of the bulk of this, and certain other types of cold matter systems is vacuum pumps. Yes large, but still practical for maritime uses. While cold matter labs cannot comment on certain specifics of any defense-related implementations, there is coverage in the press about successful tests by various quantum navigation labs for naval applications. The instruments themselves are well-proven for detecting movement, but there is a whole next level in algorithmic development ahead.

“Building the hardware is one thing, said Cotter, “However, you need to put that into a computer with some algorithm that converts those measurements into a change in position in a map frame, which would be the surface of the earth. A lot of very clever people have spent a very long time figuring out these algorithms and optimizing them and tuning them.”

“Rather than reinventing the wheel, I think it would be useful [for different research groups to collaborate] to figure out how good these sensors really are,” said Cotter. “So, you can give them an accuracy over time. It’s slightly more complicated than that, though, because I think the quantum-enhanced sensors behave slightly differently from classical ones. There’s probably going to be some tuning of the algorithms that’s required to get the best out of them. So that’s certainly something that we’re looking at.”

Of course, a key challenge for cold atom devices is in seeking to miniaturize them for more portable applications. Both Cotter and Barrett noted that for the navigation of ships, large aircraft, and trains, size is not as much of an issue as it would be for geomatics field applications. “I think for horizontal measurements of acceleration, there’s always a going to be a limit to [size],” said Cotter. “Because, like you alluded to earlier, you have to work in the presence of gravity. You can’t turn gravity off, the atoms are always going to be falling transversely through a beam, and so that’s going to put a limit on the size of the system.”

“There’s a relationship between the size of the system and how long you want to navigate for,” said Cotter. “If you don’t want to navigate for quite as long, there are routes towards making it more compact. Whether that’s ever going to get [significant] miniaturization, I don’t know. However, for short-term navigation, say mining, that’s where conventional gyros don’t hold up all that well, this represents a potential application. We’re working with [a rail system] on some potential tests.”

Quantum Antennas

Different frequency bands almost always require different types of antennas, purpose-designed, tuned, filtered, amplified, and more. When GNSS receiver antennas first began to accommodate more than one constellation (i.e., adding Glonass and U.S. GPS “Navstar” to the same receiver/antenna) this was often done by stacking one “patch” style antenna on top of the other. This, and other methods for accommodating GNSS signals across various RF bands have worked well.

But what if, as many propose for PNT resilience, anti-jamming, and anti-spoofing, developing multi-sensor approaches that leverage broader bands of RF could complement GNSS? Examples: low-earth-orbit LEO satellite navigation systems (like that which Xona Space Systems is building). Other approaches being developed include leveraging signals of opportunity, enhanced gyros (including quantum), plus image, lidar, and electromagnetic map stabilization. Using only conventional antennas, a future GNSS+ surveying “rover” might end up looking like a miniature “antenna farm”. Quantum antennas could remedy this.

Rydberg atoms, as described earlier, are proving to be a powerful approach to broad-spectrum antenna design. Designs using this approach are much more practical to miniaturize, as we have seen with proposed quantum magnetometers, than cold matter sensors (like gravimeters and “quantum gyro style” navigation systems).

Right: An experimental quantum antenna, using Rydberg atom techniques, that can detect the RF spectrum from 0 to 100 GHz. Source U.S. Army press release.

The U.S. Army Research Laboratory has announced the development of a quantum antenna that can detect the entire radio frequency spectrum, from 0 to 100 GHz. An application that uses a combination of signals across a broad range of bands would be much harder to jam or spoof. Of course, as with many defense applications, the finer details of this particular development are somewhat secretive. I did though, ask several unrelated quantum sensor developers how a quantum antenna could bring such capabilities, and was given shorthand explanations.

As Rydberg particles, though only in the excited state, further from the nucleus of the atom, are super sensitive, it would be possible to have different populations of excited atoms that could be interrogated for different electromagnetic perturbations, or wave and frequency characteristics.

Other emerging positioning and navigation technologies could greatly benefit from quantum antennas. One is the POINTER system, a joint NASA-JPL and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) design to enable first responders to “see through walls” (signal-wise), to help locate body beacons inside structures from outside.

POINTER uses magnetoquasistatic (MQS) Fields, using 3-antenna arrays (with XYZ orientations) on both the base (on a fire truck outside) and locator units (for the first responders inside). While the results have been astounding, and suitable for small/medium structure applications, there are limitations to the range, what materials signals can pass through, and precision, making it unlikely to find applications in geomatics. Quantum sensing might change that.

“Today, one of the limitations in quasistatic magnetic systems, such as with POINTER is just trying to get the device as small as you can get,” said Dr Darmindra Arumugam, Group Supervisor, Senior Research Technologist, and Program Manager at Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech. “The big limitation to making these devices very small is the size of the antenna. So, a lot of care is taken in designing those antennas that you see [showing me a board in the POINTER device]. It’s very difficult to make them considerably smaller than perhaps a few inches or an inch in dimension.

“And that’s just the antennas. There’s a lot of electronics as well, microcontroller microprocessors, etc.,” said Arumugam. “Atomic sensors, particularly magnetic-based atomic sensors, can improve the sensitivity and also reduce the size considerably. So that is a potential future at the moment.”

Left: Dr Darmindra Arumugam, Group Supervisor, Senior Research Technologist, and Program Manager at Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech.

“With cold atom approaches, size is an issue as you need to cool the atoms. With Rydberg atoms, this is essentially room temperature and can be relatively small,” said Arumugam. “You do not need to cool the atom, so you do not need the large cooling lasers and vacuum pumps of some cold atom systems. Some Rydberg atom sensors can use tiny glass cells, as Dr Kasirajan described earlier in this article, for instance, quantum magnetometers for underground utility mapping.

“You’re just exciting the atom to a high principal quantum number, or to a known principal quantum number, where you operate in the magnetic case,” said Arumugam. “There are many ways to do it, but one way that you would do it for a future version of POINTER, for example, would be to excite to a high principal quantum where the atom is sensitive to fields, then use an external exciter to provide some spin to the electron and study its behavior as it decays, and use that mechanism to detect fields.”

Could a quantum-enhanced MQS approach benefit geomatics applications? Perhaps within certain ranges and precision budgets, but with the advantage of being able to work in a GNSS-denied environment. In addition to being leveraged for indoor applications like first response, it could also be suited for work outdoors, as part of the type of multi-sensor approaches that Project Sextant envisions, for resilient PNT.

Lidar, Radar, and Cameras

Reality capture technologies work by detecting electronic and/or photonic energy, and quantum sensing approaches, with their super sensitivity, could potentially enhance any of these. For example, quantum entanglement camera technology is being broadly researched, and there have been many successful tests (though in very controlled environments for now).

Quantum entanglement cameras can operate by detecting the state of entangled photons far away. This is another example of a kind of “splitting” for different types of interferometric approaches.

Quantum lidar can apply similar approaches, as can quantum radar. There are too many varied approaches leveraging, for instance, quantum entanglement and squeezing, that we can only scrape the surface of what is possible. When certain tests are successful, assumptions about reality capture sensors might need to be rethought. For example, one set of tests for a type of quantum-enhanced lidar successfully imaged underwater, in turbid conditions.

Right: Quantum lidar, capturing high detail, even in turbid underwater conditions. Source: Heriot-Watt University

Quantum illumination offers much higher sensitivity and improved signal-to-noise (SNR) compared to the utilization of classical light beams. There are some fundamental similarities as certain approaches use a comparison between signal beams and “idlers” involving joint measurements of their in-phase and quadrature components; there can also be photon counting detection methods. As such technologies are further developed and tested, the suitability and practicality for reality capture solution implementation will be much clearer, though this might take some time.

There is a lot of development going on in quantum radar, for space applications to vehicular autonomy. The latter has been a driver (no pun intended) for rapid advancements in cameras, lidar, and radar. Each has certain attractive behaviors, but also limitations. Quantum enhancements of each can overcome some of these limitations, like range, sensitivity under various environmental and light conditions, reducing ambiguous returns, and more. R&D for consumer and mass market applications, particularly for vehicle autonomy may have downstream benefits for geomatics applications. It is not out of the realm of possibility that say, surveying total stations, or GNSS rovers might feature all of the above. We’ve already seen multi-sensor development for rovers and total stations, quantum could make this trend even more exciting.

“One of the big challenges in radars today is that they are not very tuneable systems, and they need to be big because of the antennas,” said Dr Arumugam of NASA-JPL. “And you’d need different antennas for different bands.” A multi-sensor package might benefit from having different radars in different bands, to overcome environmental conditions, desired ranges, etc. Because they might need different (and large) antennas, you might have to make some hard design decisions.”

“Currently, it is very difficult to develop compact systems that can be tuneable and operate over all the bands that we care about, all the bands that we care about,” said Arumugam. “Say you need a radar/radiometer system that is doing passive radio monitoring at say, 100 GHz, then another band at one GHz doing active radar mapping of some earth variable like soil moisture. It is almost impossible to use the same electronics, RF, and front-end antenna for those two bands.”

Rydberg atoms, as leveraged for antennas and other quantum-enhanced tech, are again part of the answer. “We excite the atoms to pull electrons far from the core, and with superposition.

Creating a diploe situation, that makes that atom very sensitive to incoming RF fields,” said Arumugam. “The key is to tune to the state that it’s in. If it was more sensitive, it could reach all of those bands. So, atom-based techniques like Rydberg radar are focused on tuning. You tune the atom differently, and it’s now sensitive enough for this-or-that band—you can make very sensitive detectors that cover MHz up to THz—it’s just mind-blowing because it changes the game on how radars are done today. As a result, there’s a lot of activity on this topic and I’m leading a large team developing these techniques.”

Quantum radar and conventional radar could have an increased presence in geomatics applications moving forward. For instance, look at the small form factor and low costs for short and medium-range commercial radars that have been integrated into multi-sensor tech packages for autonomous vehicles. These are used for blind spot detection, rear collision alerts, cross-traffic warnings, and long-range adaptive cruise control. Cameras, lidar, and radar each have strengths and weaknesses for autonomous systems, which is why most systems use combinations. But how could radar enhance reality capture solutions?

One application could be for position stabilization of other sensors, much like cameras and SLAM lidar are used to augment GNSS+IMU for mobile mapping systems. Radar could also help tackle a persistent challenge facing lidar and camera-based data capture: vegetation. While lidar, especially lidar with multiple returns, can “penetrate” (e.g., find gaps in vegetation), to detect features underneath, and provide at least some ground shots (depending on the type and density of vegetation). However, this is still sub-optimal. Camera-based capture is even less capable of dealing with vegetation. In wide open areas, mobile, and other multi-sensor mapping can be impeded by, for instance, roadside vegetation. Often supplemental points need to be captured by conventional surveying methods.

One power of radar is that it can be tuned to “see through” certain types and densities of vegetation. Commercially produced foliage penetrating radar (FOLPEN or FOPEN) systems have been around for years, though typically for airborne and defense purposes (some can also penetrate, in a limited manner, the soil underneath). These can be tuned to specific conditions or objects of interest, though such systems are often large.

What quantum radar could offer, as Dr Arumugam noted, is tunability for a broad range of bands on one device. Together with advances in quantum antennas, there could be potential for miniaturization, to the point where FOLPEN could be added to multi-sensor mobile mapping systems. And, depending on the degree of miniaturization, and power requirements, it might not be out of the question to someday see such radar added to say, the camera and lidar elements we are beginning to see more of, on GNSS rovers. And reality capture robots that are almost here.

Precise Time

Most, if not all the quantum sensing approaches we have examined, are extremely dependent on precise time. For some, this is the use of internal, relative time markers. For others, synchronized wide area, or even global time is essential.

For example, it was evident, after the success of the 1960s testbed satellite navigation system Timation, a project of the US Navy (shepherded by pioneering scientist Roger Easton), that a future envisioned global navigation system would leverage precise time. This spawned the U.S. GPS “Navstar” system, which featured the time and signal-ranging approaches for all satellite navigation systems (GNSS) to follow. There is precise time determined from a ground segment, and clock corrections are transmitted to the atomic clocks on the GNSS satellites. Time (and time corrections) are then broadcast to GNSS receivers (that do not have atomic clocks).

Quantum physics has been part of atomic clock-enabled precise time synchronization applications all along. However, R&D has not stood still. For example, the newest of a series of navigation test satellites (NTS-3), set for launch, will carry multiple atomic clocks to test.

Above: There are chip-scale atomic clocks, precise for certain applications. And there are very precise mid-sized compact atomic clocks (left), as used in the terrestrial beacon-based positioning system of NextNav (right). Source: NextNav

As an aside, especially as there is so much press about GNSS vulnerabilities: one of the primary missions of NTS-3 is to test approaches to boost resilience and protection of GPS. Of particular note is an encryption approach called Chimera, which includes unique satellite “watermarks” and a kind of “delayed key” (i.e., that means that a signal already received could not be spoofed). Another significant development is the use of software-defined radios. This means that certain types of upgrades and new approaches could be implemented remotely (reducing the need to launch new blocks of satellites each time there is a technology change).

Quantum methods will benefit timing applications. Like enhancements for closed-loop RF-based, fiber-based precise time reference networks, and encrypted satellite time services. Chip-scale atomic clocks have been available for quite some time, and continue to evolve. While lower in precision than their full-scale cousins, these tiny atomic clocks are precise enough for certain applications (e.g. synchronizing time markers for underwater vehicles and systems). There are in-between-scale atomic clocks, like those employed by NextNav for its beacon-based terrestrial positioning service.

Could there be a precise atomic clock integrated into say, your mobile mapping system in the future? As quantum sensing development continues, it may not be out of the realm of possibility. One of the challenges of top-tier atomic clocks is not just size and cost, but susceptibility to movement, jarring, and shaking. However, it was recently announced that a precise atomic clock has been tested that (per initial reports) works well even when transported over long distances.

Quantum Comms

A succinct explanation of quantum communications and some of its most attractive features is from quantum solution development firm Keysight:

“Quantum Communication is a method of transmitting information using quantum mechanics principles. One of the key features of quantum communication is that it allows for the secure transmission of information. This is because any attempt to intercept or eavesdrop on the transmission would cause the quantum state to collapse, alerting both the sender and receiver to the breach in security.

“Quantum communication can be achieved through various methods including quantum key distribution (QKD), quantum teleportation, and quantum entanglement. These techniques have potential in areas such as cryptography, secure communication, and quantum internet.”

Quantum technologies could, and likely will shortly, be a disruptor of legacy communications approaches. This would encompass not only those applications highlighted in the quote from Keysight but also satellite communications.

How would these implementations benefit geomatics? Consider potential encryption, and other approaches to augment GNSS (that would help address the jamming and spoofing concerns many are focused on). But also consider the combined power of quantum computing and sensing approaches together with secure and enhanced communications. Consider say, moving massive amounts of reality-captured data to and from (increasingly popular) cloud services, processing, edge-AI, and enabling multi-sensor solutions, as we’ve already mentioned.

These ideas are not new, and there have been decades of R&D in quantum communications, with more recent advances bringing such envisioned solutions closer to fruition.

Applications and Timelines

Before looking at geomatics-specific applications, consider that many other applications for quantum sensing represent much larger markets than geomatics. This is wonderful, as geomatics would be a downstream beneficiary, reducing the need for a lot of costly and time-consuming application-specific R&D.

As listed by Quantum Insider, key markets for quantum sensing include MRI (medical imaging), spectroscopy (e.g., for characterization of materials and chemicals), enhanced satellite navigation and communications, inertial systems, detecting gas, and other types of leaks, manufacturing (e.g., chip quality monitoring), remote target detection (e.g., defense), broader application of multi-band radar systems, microscopic imaging, quantum computing, and communications. And as we’ve examined, imaging, lidar, gravimetry, and magnetometry.

Nearly every one of these focus areas could benefit geomatics—eventually. Timelines are very difficult to predict. Even the physicists I spoke with are hesitant to speculate. However, as we’ve seen in a wild century of significant leaps in geomatics technologies, when technological breakthroughs do occur (from inside or outside the related industries), real-world implementations happen far faster than anticipated.

There are a lot of clever people working and competing all over the globe to develop these technologies. With that in mind, there were a few quantum sensing approaches that could be good candidates, shortly, for advancing geomatics applications. Some will provide benefits for geomatics applications indirectly, and others may still be on the far horizon.

Quantum navigation applications (thus far) only achieve “navigation-grade” precisions. Meaning they do not have to reach the “positioning-grade” precision needed for many other end-use applications (such as geomatics). “Where is the 300m long ship?” As opposed to where is the “1cm survey control point?” However, there may be lateral benefits from quantum navigation, such as a coarse gut-check for a multi-sensor solution.

As noted earlier, and despite the wishful thinking of some who promote certain Alt PNT solutions, there is no direct “replacement” for GPS/GNSS. A complete replacement is not only impractical but would never match the global ubiquity and tremendously broad range of applications that GNSS delivers. Especially as none of the alternatives could meet such precision capabilities at a global scale.

There are hopes for certain alternatives that do not need massive infrastructure investments, like the quantum magnetometry map solution we examined earlier. However, this is navigation-grade precision, and not survey-grade. Quantum gyroscopes: the same. Practical for navigation, but due to size, cost, and low precisions, not practical or useful for geomatics directly.

In addition, there are trade-offs. Many classical systems, inertial systems, for example, have faster measurement bandwidth, but poor drift characteristics, while some quantum systems have small drift profiles but can be slow in deriving and delivering measurements. It varies a lot from system to system, approach to approach.

Quantum technologies will drive many other PNT solutions and can improve the robustness, resilience, reliability, and security of GNSS. This by augmenting, complimenting, and providing independent values to help detect compromised solutions (intentional or unintentional). In some cases, they already are.

However, there are no magic bullets. No matter what the solution or technology, there will always be a specter of potential mischief. Even inertial measurement systems (IMU) can be spoofed; especially popular MEMS components used for accelerometers, electronic gyroscopes, etc. That is why multi-sensor approaches are seen as the future of ensuring PNT resilience and continuity.

One quantum technology that we may see commercially within a few years, is quantum magnetometry, for underground pipe detection. This is mainly due to the relative simplicity of a Rydberg atom system (as opposed to many cold atom systems). It can be miniaturized and could be reasonably affordable.

Commercial quantum gravity meters and gradiometers are already here, but large and costly. The prospects for miniaturization are low. But even at current size and costs, they can be deployed to improve gravity models (geoid and geoid difference models) essential for geodesy and surveying. They could even be deployed to develop highly refined gravity models for small areas, like a city or a project.

Above: As a fun exercise, I put some of the conceptual ideas from my article research into a bot to see what it would come up with. While amusing, the realistic prospects of quantum sensing in geomatics field data collection instruments might not see them look much different from those of the present day. This is because quantum approaches will mostly just enhance sensor types already in use

Quantum cameras are in the development stage, and while many different approaches are being tested, there does not seem to be a breakthrough that could be rapidly and practically implemented for geomatics-type applications. Not in the next few years. Developers have told me that there are a lot of fundamental inefficiencies in present ways to trade electronic and photonic energy, that make even entanglement approaches difficult at present, but that there is a lot of very recent progress on that front.

Quantum lidar and radar have great potential. Geomatics has used interferometric approaches for decades; quantum interferometry would simply update many of those. While perhaps years away for geomatics applications, look to the massive amount of R&D going on for multi-sensor solutions for automotive autonomy and robotics for the breakthroughs. The stakes for vehicular autonomy are very high: safety of life. This means that if a solution is successful for such applications, the bugs would have been ironed out before being adapted for geomatics.

Once solutions become viable for other sectors, and become likely candidates for adaptation for geomatics, they might be productized rapidly. Perhaps 5-10 years.

Quantum antennas. These would be using Rydberg atom approaches, making it possible to make them small enough, and cheap enough for potential geomatics applications shortly. It was perhaps telling that when I quizzed GNSS engineers from various manufacturers, they indicated that they were not in a position to comment on this yet. Perhaps 5-10 years.

The challenges facing developers of quantum sensing solutions vary, depending on the approach, size, cost, precision, algorithmic refinements needed, and awareness. The more esoteric a concept, the harder it is to get potential investors and potential collaborators excited about it. The geomatics and surveying communities could do their part by talking about it more, and asking the manufacturers: “When do we get quantum?” I do though worry that once quantum sensing becomes a buzzword in the geomatics sector, some manufacturers will start to add the term “quantum” to marketing materials (or even product names) of non-quantum products. It could be a term that gets a bit overworked, like A.I. Ask them if the product is a cold atom or Rydberg atom-based.

Left: A very low vacuum and temperature chamber at the Ultracold Matter Lab at Imperial College. This underscores the challenges facing miniaturization for cold matter-based quantum sensors. By contrast, devices that use Rydberg atom approaches could be quite small, and we may see those types of technologies for geomatics applications much sooner.

The science is proven, and key technologies tested. Now comes productization, where timelines are difficult to predict. How excited should we be about this next step? It’s not bringing new tools to our toolboxes per se, not like drones and EDMs did. However, it brings improvements to existing tool types and may someday spawn new tools.

Quantum sensing might not seem like some earth-shattering “quantum leap”, but when you add up all of the other advances, geomatics might look even more like something out of science fiction—with less fiction and more science. How far are we from having robotic assistants, walking a site with us, capturing everything we ask, with some kind of Star-Trek-like “Tricorder”? Probably sooner than imagined.

Unless otherwise attributed, photos and graphics are by the author.

Be the first to comment