When the history of geospatial technology is told, a handful of people stand out as architects of the modern world. Among them is Charlie Trimble, founder of Trimble Navigation and one of the most influential figures behind the global adoption of GPS.

At the GoGeomatics Expo 2025 in Calgary, Trimble delivered a rare keynote. His talk traced the improbable rise of GPS from an unstable seven-satellite constellation to the indispensable global utility we rely on today. What the audience experienced was not a technical lecture, but a personal journey of near-collapse, unlikely breakthroughs, and persistence.

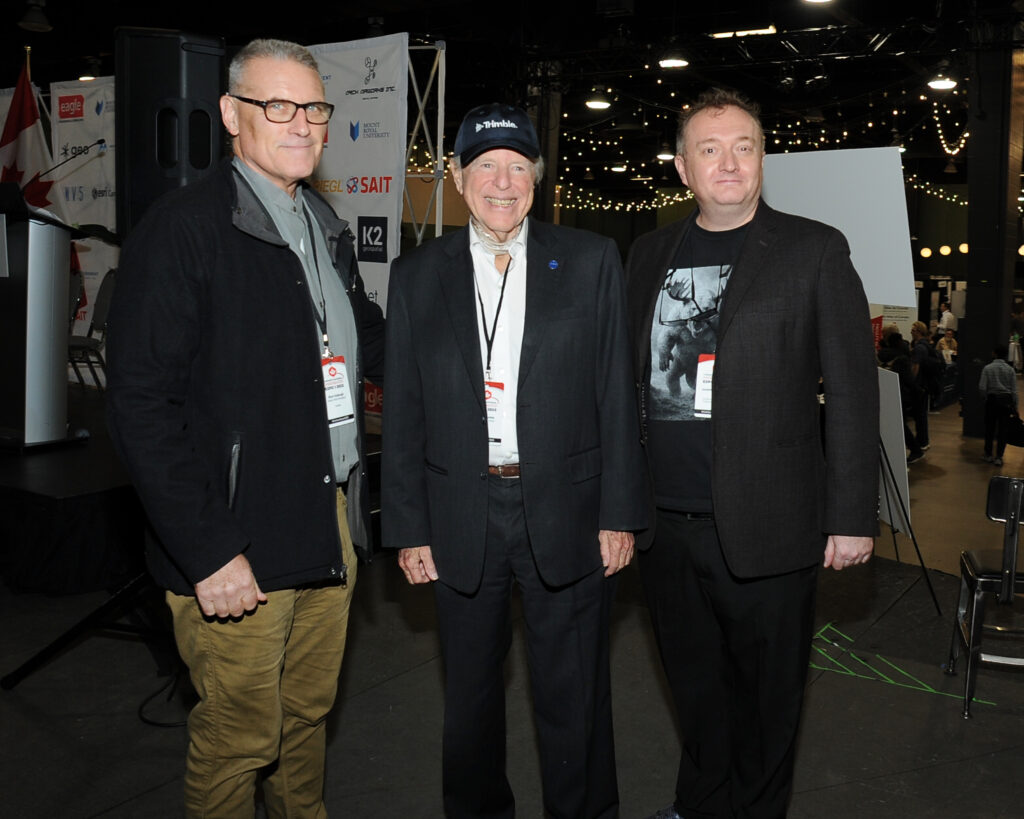

After the keynote, I had the opportunity to sit down with Charlie for a short interview. This article brings both pieces together, the story Charlie told on stage, and the perspectives he shared privately.

The Keynote: How GPS Nearly Didn’t Happen

A Family Legacy, an Unexpected Opportunity

Charlie began with humor, tracing his Scottish ancestry back to a man who supposedly saved King Robert the Bruce from a charging bull. “That DNA survived,” he joked. “Some of it ended up in me.” Then came the real story. The moment that changed geospatial history. In the early 1980s, HP cancelled its internal GPS receiver project. Trimble was small. Underfunded. Still building early navigation instruments. But Charlie saw the opportunity.

He asked himself four questions:

- Will GPS ever actually be completed?

- Could Trimble build receivers cheaply enough to reach mass markets?

- Could they leap from microwave receivers to compact computing devices?

- Could they afford the engineering without hiring government-focused HP staff?

Trimble needed several breakthroughs. They hired 20 of the brightest engineers in Silicon Valley. It took one year to design, and another full year to build and debug the first device.

Charlie went to the Navigation Boston trade show: “When I took it to the Navigation Show in Boston, I didn’t put it on display. I kept it in my hotel room because I didn’t think anyone would believe me. But word got around that Trimble supposedly had a working GPS. People kept coming to check.”

The disbelief turned into orders.

Early Markets: Selling GPS With Only Three Hours of Signal

Making a GPS receiver was only the first challenge. The signal was available just three hours a day, shifting four minutes earlier each cycle. Trimble had to think creatively about who could benefit from such a limited window.

- HP’s aeronautics division

- The Washington weather observatory

- And a small company named TUTHA, which shockingly signed for 20 units at $20,000 each

No one believed Trimble could deliver 20 units in four months. That skepticism became their competitive advantage.

Breaking Into the Oil and Marine Survey Market

Next came a high-risk move into the marine oil survey sector, an industry where customers would pay premium prices for reliability.

These clients demanded rigorous testing, expected flawless operation, and paid for value

But the rule was unforgiving: “Be first, or don’t bother.”

Then came what Charlie calls the Christmas miracle: Pioneer of Japan signed a $1 million option agreement for car-navigation technology. It was a turning point. Trimble was no longer a small Silicon Valley outsider. they had become a global player.

The Night GPS Almost Died

On January 28, 1986, the Challenger shuttle exploded. With it went any near-term possibility of launching new GPS satellites. Trimble was left with seven satellites, providing three hours of positioning per day, with each cycle drifting by four minutes. “It almost killed us,” Charlie admitted. That led to layoffs, salary cuts, and absolute focus on profitability. “We were profitable again by May for the rest of 1986” he said.

That year Trimble established its surveying franchise, introducing workflows that turned multi-hour post-processing into a viable business model for small firms.

The Global Battle That Saved GPS

By the mid-1990s, a bigger threat emerged. A satellite communications company (ICO) began lobbying globally to take 5 MHz of protected GPS spectrum and reallocate it for commercial use. They had secured votes from 47 countries. Airlines were horrified. Charlie led an emergency advocacy campaign that reached the UN’s World Radiocommunication Conference.

An American pilot gave him the trick that turned the tide: “Fax every British MP asking why the UK is prioritizing commercial interests over airline safety.”

A 10,000 faxes later, the UK reversed its position. With help from allies and a phone call to the British Prime Minister, the measure was remanded. Three years later, the final vote was 102–0 in favour of protecting GPS. “If that fight had gone differently,” Charlie warned, “GPS might never have become the global utility it is today.”

Part II — Interview with Charlie Trimble

After his keynote, I had the privilege of speaking with Charlie directly. Here is the excerpt from the conversation.

What technical breakthroughs surprised you the most in those years?

First, we managed to make first-order surveying work after the shuttle explosion. That saved us. Second, we could obtain the first L2 energy in space from 25 dual-frequency surveys. And third, the biggest surprise, that RTK was actually possible.

If you were designing GPS today, with cloud computing, AI, and edge devices available, what would change?

I wouldn’t rely on silicon accelerators. I’d do almost everything in software. Today you can run a GPS solution on an Android phone.

(He laughed about how consumer markets have moved away from dedicated GPS units)

The real markets now are instrumentation. Reliability depends on connectors and cables. That’s where failures happen.

With today’s capabilities, where is GPS still limited?

In consumer markets, GPS has ‘disappeared’ onto chips. But the high-accuracy markets (survey, monitoring, timing) are niche but absolutely critical. That will always require specialized hardware.

More than a Trip Down Memory Lane

Charlie’s reflections are more than a nostalgic trip down memory lane. They are a reminder to the geospatial community that the infrastructure we now take for granted was once a fragile, contested idea. As we move into a future shaped by AI, automation, and ever-denser sensor networks, the GPS story offers a template:

- bet early on what matters,

- defend the public good when it’s under a quiet threat,

- and keep building, even when almost no one believes you yet.

The geospatial world we live in today exists because, at several critical moments, Charlie Trimble and his peers refused to walk away.

Be the first to comment