Pingo, the name itself got me curious to find out more about it. Not to be confused with Pingu (The Antarctic penguin cartoon character that we could watch for hours without any dialogues 😛 )

Ever heard of hills filled with ice? Sounds bizarre, right? Pingos are like ice hills covered with vegetation from outside.

It’s about the oddest landform you’ll ever see – a frozen eruption, bursting in slow-motion from the tundra. “Pingo” is Inuvialuit for “small hill”. The word has been used by scientists since 1938, beginning with the Arctic botanist Alf Porsild. We’re thankful Porsild popularized “pingo” instead of the alternate name, hydrolaccolith. In fact, Porsild Pingo, near Tuktoyaktuk, is named in his honor. Pingos are a kind of “periglacial” landform, meaning they are created through processes of freezing and thawing. Covered with tundra on the outside, they contain a core of ice. They grow in much the same way that a can of pop expands as it freezes.

Difficult to believe? Check out the Pingo National Landmark of Canada here. Fancy a little stroll, It has a short route mapped through Street View that you can explore.

The Digital Mapping Project

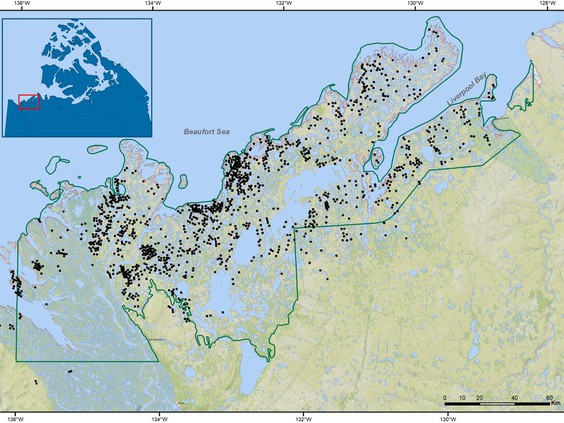

Pingos, volcano-shaped cones of ice and sand, are an iconic symbol of the Western Arctic, and thanks a recent digital mapping project, Canada just got a lot more of them. Enough to vault the Northwest Territories past neighboring Alaska as the pingo capital of North America. Recently, a digital mapping project doubles known number of iconic Arctic ‘ice volcanoes’.

Wolfe Stephen, Research Scientist at Geological Survey of Canada utilized his time at home during the pandemic, to map pingos more accurately. He used high-resolution digital imagery of the Arctic and Google Earth to scour the Lake Erie-sized area around Tuktoyaktuk where pingos are found. He identified 1,000 new pingos, nearly doubling Canada’s pingo population to 2,160. He even identified five and possibly six new pingos within the boundaries of Pingo Canadian Landmark, which formally only recognizes eight pingos including Ibyuk Pingo, Canada’s tallest and the world’s second-tallest pingo. It reaches 49 metres (about 161 feet) in height and stretches 300 metres (about 984 feet) across its base.

How are Pingos formed?

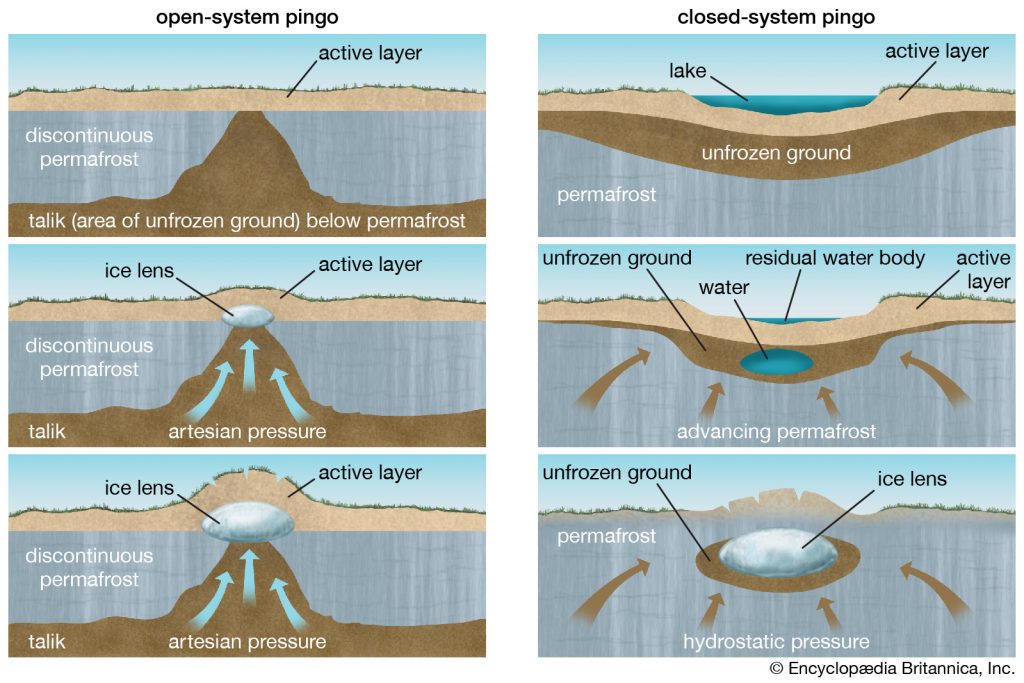

Researchers and scientists distinguish between two types of Pingos. Closed system pingos (up north formed in cold permafrost in continuous permafrost zones and open system pingos (in boreal forests with discontinuous permafrost). Pingos often form in old lakes, that have drained. Cold climatic conditions cause permafrost to reestablish itself at the bottom of drained lake. This permafrost now squeezes the unfrozen area to create a pressure that eventually leads it to push the ground up, creates a mound and freezes again on the top. Its a slow process, They might be still growing when you look at them, therefore also called living features.

Pingos and Climate Change!

Apart from being a natural wonder, Pingos are also key indicators of climate change and the state of the permafrost that underlies them. About five per cent of the pingos identified in the 1970s have been lost to coastal erosion and Wolfe has identified about another five per cent that have collapsed because their ice cores melted away. Source : https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/pingos-galore-digital-mapping-project-doubles-known-number-of-iconic-arctic-ice-volcanoes

For centuries, pingos have acted as navigational aids for Inuvialuit travelling by land and water. They are a convenient height of land for spotting caribou on the tundra or whales offshore. According to Wikipedia, Pingos are also found in Greenland, Central Asia, Alaska, Siberia and scholars have seen some pingo-like features on Mars, though there is not enough evidence to class them as pingos.

References

- https://nnsl.com/tag/arctikgis-geosympos2020-inuvik-inuvikdrum-pingo/

- https://www.narcity.com/en-ca/travel/yellowknife/pingos-in-canada-are-so-unique-weve-got-one-of-the-tallest-in-the-world

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/northern-national-parks-pandemic-1.5663708

Be the first to comment