People open maps on their phones every day to check a route, locate a place, or understand what surrounds them. It feels simple, but a long history stands behind that moment. The journey to modern GIS began with early attempts to measure land, understand the shape of Earth, and record locations with accuracy. Later came satellites, digital tools, and the systems that hold spatial data together. This article looks at how GIS came to be and why its foundations still matter today.

How Our Need for Place Began

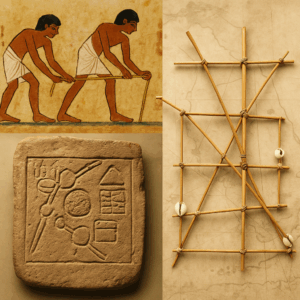

From the very beginning, humans have cared about understanding their surroundings. Long before digital tools, people mapped coastlines, fields, and travel routes using the resources they had. Ancient Egyptians measured farmland along the Nile after each flood using ropes and simple geometry. Polynesian navigators crossed vast oceans by reading stars and waves. Early mapmakers from China, Greece, and the Arab world recorded landscapes with careful observation.

These early efforts show that spatial thinking is not new. It is a natural part of how people make sense of the world. GIS continues this same human impulse, only with better tools and greater accuracy.

Seeing Earth Beyond a Perfect Sphere

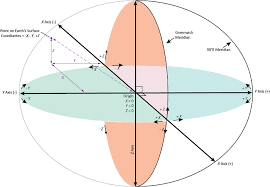

Once people began measuring land more carefully, they discovered something surprising. Earth is not a perfect ball. If you hold an orange, you will see bumps and dents. If you gently press a rubber ball from the top and bottom, the shape changes slightly. Earth behaves in a similar way.

Scientists realized that the planet is slightly flattened at the poles and wider at the equator. To capture this shape mathematically, they created reference ellipsoids. These ellipsoids are smooth, simplified shapes that represent Earth well enough to support accurate mapping.

This understanding became a turning point. Without an agreed shape for Earth, there would be no common starting point for maps.

The Quiet Science That Holds Everything Together

As measurements improved, a new field emerged to support them. This field is geodesy, the science of measuring Earth and defining where things are on its surface. Many people use GIS without ever thinking about geodesy, yet it forms the stable base that every coordinate system depends on.

A simple analogy helps. Place a sticker on a hard wooden table and its position is clear and stable. Place the same sticker on a soft pillow and the surface shifts under it. A map needs the stable surface, and that is what a datum provides. A datum is the reference frame that tells the map where Earth begins.

With this, maps from different places and times can line up correctly. Without it, two datasets might look close at first glance but sit far apart in reality.

Why Flattening Earth Creates Different Maps

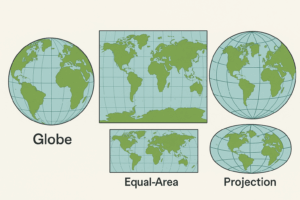

After agreeing on a reference shape, cartographers faced a new puzzle. How do you take a round planet and place it onto a flat surface without cutting or stretching it? Anyone who has peeled an orange and tried to lay the peel flat knows this is impossible without distortion.

To solve this, mapmakers created projections. A projection is simply a method that transfers locations from a round surface to a flat map. Each projection preserves something different. Some keep shapes consistent. Others preserve area. Others keep directions clean for navigation.

Because no projection can preserve everything, maps will always look slightly different depending on the method used. Understanding this helps explain why one map of a country looks stretched while another looks compressed. Both can be correct within their purpose.

Satellites and How They Guide Us Today

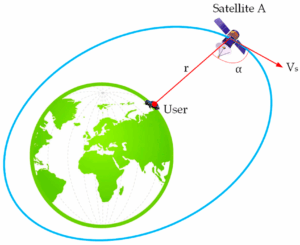

Modern location tools rely on satellites that orbit Earth. When your phone shows your position, it listens to timing signals sent by several satellites. By comparing when each signal arrives, your phone calculates how far it is from each satellite, and from that it identifies your location.

This process depends entirely on accurate reference frames and datums. If the reference frame shifts, every position shifts with it. National agencies and scientific organizations work constantly to refine these systems so that our maps and navigation tools stay reliable.

Without satellites and the precise timing they provide, GIS would lose much of its power. Accurate positions allow spatial data to line up correctly across different platforms and devices.

The Moment GIS Became Possible

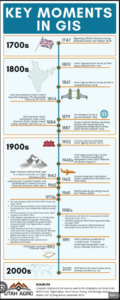

GIS took shape when computers became strong enough to store, compare, and analyze spatial information. In the 1960s, Roger Tomlinson led a project in Canada that became the first working GIS. His idea was simple but revolutionary. Instead of drawing map layers by hand, he created digital layers that could be turned on or off and analyzed together.

Tomlinson later reflected on how new and unfamiliar the field was at the time:

“The early days of GIS were very lonely. No-one knew what it meant.”

This underscores how groundbreaking his work was. GIS opened a new world. Governments could analyze land use more efficiently. Researchers could explore patterns with more clarity. Communities could understand their surroundings better.

The System Behind Every Map

It is easy to take GIS tools for granted because they feel fast and intuitive. Yet every click depends on contributions from many fields. Surveyors measured land boundaries by hand. Mathematicians built the formulas for projections. Geodesists defined the reference frames. Engineers designed satellites and receivers. Programmers wrote the tools that display and analyze the data.

Jack Dangermond, founder and president of Esri captured the creative spirit behind GIS in a simple way. He noted that “the application of GIS is limited only by the imagination of those who use it.”

This reminds us that GIS stands on collective work from many fields. It is not only a technology. It is a long collaboration shaped by measurement, mathematics, engineering, and the desire to understand our world.

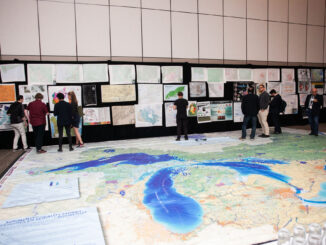

Image source: Utah AGRC.

Why Understanding the Foundation Helps Us Work Better

Many GIS users learn through hands-on tasks. They learn how to visualize data, run analyses, and build maps, but may not spend much time on the deeper systems behind the software. There is nothing wrong with this. GIS is designed to be accessible.

Yet knowing the basics of projections, datums, and coordinate systems makes our work stronger. It helps prevent misalignments that shift buildings or roads. It helps us choose the right tools for the job. It gives us confidence when working with spatial data from different sources.

This knowledge is not about adding complexity. It is about building clarity and making our maps more trustworthy.

Preparing for the Future of GIS

GIS is evolving quickly. New satellites and sensors are expanding the ways we collect information. Cities are using spatial models to plan ahead. Conservation groups rely on satellite data to protect ecosystems. Humanitarian teams use GIS in emergencies to save lives.

Michael Goodchild, a leading thinker in GIScience, described this growth clearly:

“A flood of new web services and other digital sources have emerged that can potentially provide rich, abundant, and timely flows of geographic and geo-referenced information.”

This pace of change highlights why the foundations matter. When GIS professionals understand the systems beneath the tools, they build stronger projects, avoid common errors, and prepare themselves for new innovations.

Conclusion

GIS is more than a set of tools. It is the result of centuries of human curiosity, measurement, and innovation. It grew from early mapping traditions, careful observations, mathematical work, and modern satellite systems. Every map we open carries this long history within it.

Understanding the foundation does not make GIS harder to use. It makes it more meaningful. It helps us appreciate the effort behind each layer and the people who shaped the way we see the world. As GIS continues to expand, this awareness will guide how we use it, improve it, and share it with future generations.

Happy GIS Day. Here is to the people, tools, and ideas that keep pushing geographic understanding forward.

Be the first to comment