Projects built on well studied and understood terrain can combat the risk of catastrophic consequences of natural disasters. A powerful reminder is the 2002 Denali Fault earthquake, a magnitude 7.9 event that tore through the Alaska Range about 90 miles south of Fairbanks.

The quake violently displaced the ground beneath the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), damaging key sections and illustrating how vulnerable critical infrastructure can be when placed across active geological zones.

However, the pipelines didn’t break. The Denali earthquake became a landmark case in how understanding terrain can prevent catastrophe.

Today, Canada is preparing to make a similarly high-stakes decision. A new multibillion-dollar pipeline proposal stretching from Alberta to the Pacific Coast has ignited fierce political and environmental debate—but beneath those arguments lies a quieter, far more consequential question: Do we truly understand the ground this pipeline would cross?

How was Denali Pipeline designed

In the early 1970s, as seismologists and geologists worked on the initial design of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, they conducted extensive studies of the Denali Fault system. Although they could not pinpoint the exact location where the fault would rupture in relation to the pipeline corridor, they developed detailed scenarios based on the best available science.

Their models estimated that the region could experience an earthquake of up to magnitude 8.0, with a potential horizontal displacement of about 20 feet and vertical movement of roughly 5 feet. Remarkably, these predictions proved to be highly accurate.

On November 3, 2002, the Denali Fault produced a magnitude 7.9 earthquake—one of the largest in North America in decades. The pipeline corridor located just 1,900 feet from the rupture, experienced horizontal and vertical shifts that closely matched the scientists’ original estimates.

The violent ground motion damaged several pipeline supports near the fault, yet the pipeline itself did not rupture. It survived because engineers, informed by the seismic studies, had designed the structure with flexible supports and intentional “slip zones” to accommodate exactly this kind of ground displacement.

The outcome raises an important question: what would have happened if geologists and seismologists had not studied the land?

Challenge for Canada

Before the pipeline construction begins, fundamental questions must be answered: Which regions will the pipeline cross, and what impacts might it have? These uncertainties are central to the debate.

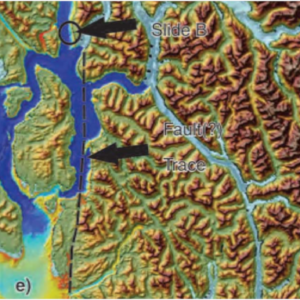

Although the exact route has not been finalized, the proposed oil pipeline is expected to run from Edmonton, Alberta, across the Rocky Mountain Trench, and through the sparsely populated northern interior of British Columbia. The line would likely terminate at the Douglas Channel—a rugged fjord system and one of the busiest potential harbours for shipping crude oil to Asia. Its deep, narrow waterways make it a practical site for a marine terminal, where large tankers could load oil for export.

The Geological Survey of Canada has recognized a tsunami risk and the presence of a potential seismic fault within Douglas Channel, in the vicinity of Kitimat in 2012 study. A scholarly article authored by the Geological Survey in collaboration with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans reports that two significant prehistoric landslides occurred in Douglas Channel, which generated substantial tsunamis. The study further suggests that these landslides may have been induced by seismic activity along the identified fault line.

While modern engineering can significantly reduce the risks of building pipelines in seismically active regions, this is only possible when the terrain is well understood. And in key areas—particularly the Douglas Channel—critical knowledge gaps remain.

Recent high-resolution sonar mapping by the Geological Survey of Canada revealed roughly 100 historic landslides within the fjord. Many were small, but several were exceptionally large and carry the potential to inflict severe damage—not only to tankers, but also to nearby towns and critical infrastructure.

Compounding the risk is the fact that the landscape around the Douglas Channel closely resembles parts of southeast Alaska, where the Lituya Bay mega-tsunami occurred. This similarity raises difficult questions about the worst-case scenarios for a pipeline that would rely on safe marine access in a geologically volatile environment. The Rocky Mountains and the surrounding coastal ranges sit atop complex tectonic structures that have not been thoroughly mapped.

Conclusion

The Denali earthquake showed that when scientists thoroughly understand the land, engineers can design infrastructure that survives even the most violent natural events. Canada now faces a similar moment of decision. The proposed pipeline linking Alberta to the Pacific Coast carries enormous economic potential, but it also crosses terrain whose geological behaviour remains only partially understood. With the Douglas Channel revealing evidence of massive past landslides and the coastal landscape echoing hazards seen in places like Lituya Bay, the risks are real—and potentially catastrophic.

Before construction begins, Canada must commit to the same level of rigorous, science-driven assessment. Comprehensive mapping, transparent research, and meaningful engagement with affected communities are not obstacles; they are the only path to building infrastructure that is both responsible and resilient. The question is not whether the pipeline can be built, but whether it will be built with a full understanding of the land it depends on.

Be the first to comment