Download GNSS Base Data Sooner Rather Than Later

Whether it is for mobile mapping, drone work, asset mapping or surveying static campaigns, taking steps early in the process a confirm the availability, completeness, and quality of the base files you intend to use for post-processing, can save a lot of heartache.

If you are not using real-time GNSS (and for many applications that is not the best choice) you will be post-processing your observations against base data files. For instance, common Rinex format files, logged on a local base or network on an hourly or daily basis.

While you may be doing a large mobile mapping or drone project, and might not do the post-processing until days, weeks, or even months later, the best practice is to secure the base files almost immediately after your field operations. Even if you are using a local site base, you should download and examine the base files to ensure they are complete enough, and in the data rate and format that you need. That way you will not be in for any frustrating surprises when you do get around to the post-processing step. If you base local base data is incomplete (or the base did not log as planned) you may be able to get base files from other sources. However, you may find that those externally sourced files may not be retained very long, may not be at the high rate you need (decimated over time to lower rates to save space), or shunted off to academic or science archives undergoing multiple compressions.

Surveyors, who were dependent on post-processing before the advent of real-time GPS/GNSS were quite familiar with the challenges of obtaining base data, either by setting up arrays of temporary bases, and/or knowing the ins-and-outs of what resources there were for data from permanent bases. While some things have changed, some have not when it comes to base data files, we can learn a lot from those early pioneers.

Nowadays, there are many more people using high-precision GNSS for wide variety of applications. So much has been automated, but when the automation does not work, you need to know how to fly-by-the-seat-of-your-Rinex to get the job done. It is all too easy to get comfortable with the instant positioning afforded by real-time resources: base-rover, real-time networks (RTN), and satellite delivered precise point positioning (PPP). The reality is that those are not always available (or may not meet your precision needs). For instance, you may be too far out of cell range to use RTN, limited sky view may not make the use of L-Band satellites broadcasting PPP practical, or a solution like post-processed kinematic (PPK) that couples the inertial measurement unit (IMU) of your drone or mobile mapping system with the GNSS can yield a tighter solution. A lot of new users out there may not jump right in to post-processing and might find out the hard way that when they need to, waiting too long to ensure you have sufficient and appropriate base data can be a real problem.

Here’s a scenario I have seen too often. A mobile mapping, drone, or GIS mapping operator postpones post-processing (for whatever reason) until six months or more after the field work was completed. They might assume they can always get base data files from federal, regional, local real-time network, or science portals. However, they might find for instance, that the local network may only keep files for immediate download for a month or so, then files are archived by an academic or scientific entity (indefinitely). Then they might find that the base files are no longer 1-second (1Hz) and are now (decimated to save archive space) to 15-seconds or 30-seconds. To find the files can also involve navigating flat directory structures, with observation files organized by Julian date etc., and they may have been compressed twice. Or, they go to the user friendly federal archive and can easily find files for the time period of their field work, but they may be from bases that are GPS-only, whereas they planned to post-process multiple constellations.

Resources

A best practice for many GNSS field operations is to set up your own base and set it to log static files in exactly the data rate and format you need, though this can add time/costs to your project. Permanent bases are quite an appealing resource; but get to know more about them. Even if you set up your own base you may find out after-the-fact that you might not get exactly what you wanted. A fallback/backup is to obtain base data from one or more publicly accessible archives. However, these can come with certain caveats.

Using examples in North America (through the situation is much the same across the globe) you may be able to obtain free base data from a local or statewide real-time network (RTN). Many (but not all) RTN, be they public, private, or cooperative, make static data readily and freely available. This is often through a user-friendly file download portal where you can choose custom orders of multiple stations data, time periods, data rates, formats, and multiple constellations. Mostly, base data is logged at 1-sec intervals, as hourly files. You can order files covering one or more hours and they will be prepared for download as single files for each base you select.

For practical reasons though, this instant access may only be offered for a retention period of a few months, thereafter the data is archived in a flat directory structure and/or sent to an external archive. Archives might require a bit more time to navigate, download and decompress. More on that later.

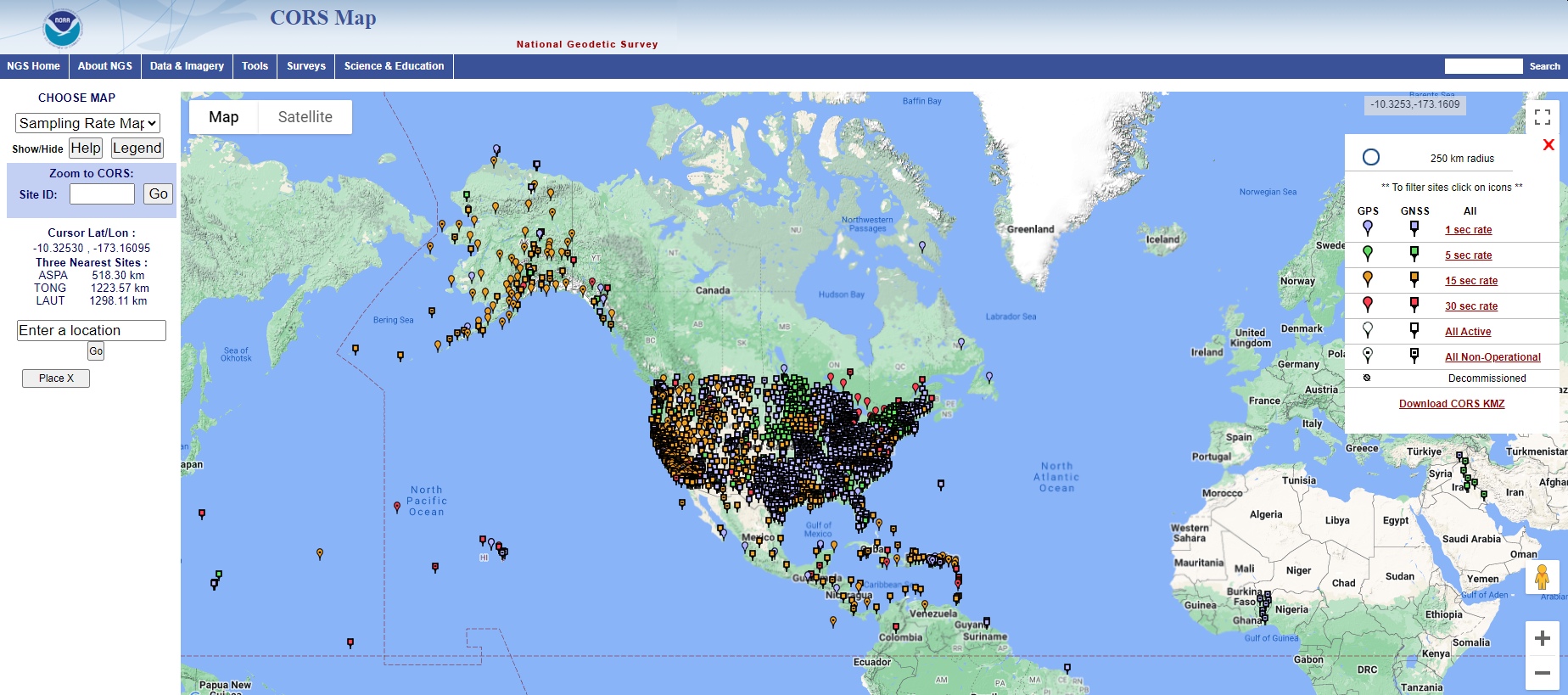

In the U.S., the National Geodetic Survey archive of data from thousands of continuously operating reference stations CORS goes back many years. However, older data may be single constellation only, and may be a lower data rate. An old flat directory navigation option is being retired, and the new User-Friendly CORS (UFCORS) is a wonderful free resource for base data from thousands of CORS across the country. However, CORS density is not even; you may find a wealth of CORS in your local vicinity with baseline lengths that suit your post processing needs, but you might find they can be somewhat sparse. Check the CORS map before planning your field work. Note data rates and availability. And click on sites to see what constellations they log. A key benefit of the NGS CORS is that you get a datasheet and sitelog for the station, giving you a base position with high fidelity to a published national reference framework (e.g., NAD83-2011 Epoch 201.00, etc.)

National Geodetic Survey CORS Map

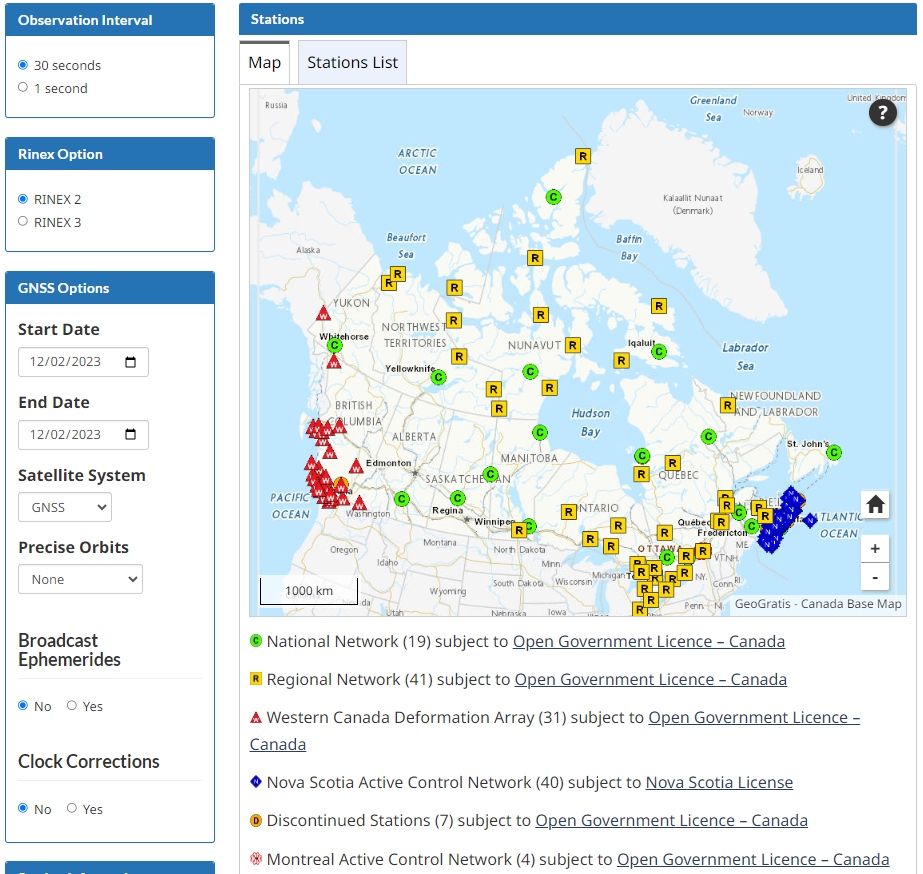

In Canada, there is the Canadian Active Control System (CACS); you can navigate the site and find static base data. CACS also has a page listing some of the real-time networks (RTN) in Canada that could be a resource for base data.

The Canadian Active Control System (CACS)

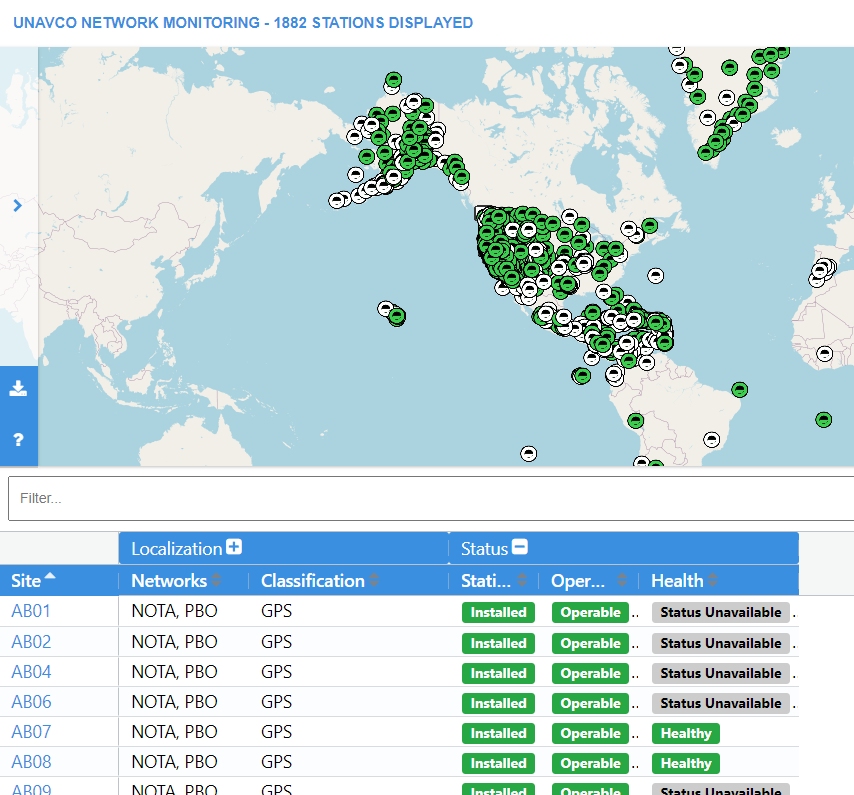

There are academic and science networks of reference stations. For example, the Plate Boundary Observatory (PBO) network of Earthscope (a Science Foundation sponsored program) that has over a thousand stations, mostly across the western U.S. and Alaska (mostly operated by the UNAVCO cooperative and science partners). While some of these are also NGS CORS (and for those you can get files from the UFCORS portal), files for most of the others are available via the PBO portal. You can drill down into the data for a station (though you may need to register with PBO) to get datasheets and archives of Rinex data.

Earthscope PBO Map

There are caveats. If you look at any Rinex file near the top of the file, you will see a line labelled “APPROX POSITION XYZ”. These are the Cartesian coordinates. In some cases, and from some resources, this might be the resolved position on a published reference framework (datum), but in most cases it is just what it says: estimated. The PBO Rinex files are fine, but they do not publish a position on the national reference framework (but rather on global frameworks, in data sheets). If you want to use files from this, or other achieves where the reference framework may not be readily apparent, download 24 hours of data and upload that to the NGS automated post processing service (OPUS), or the Canadian PP-based service, and get a position stated in terms of the national reference framework. If you drill down into the data page for a PBO stations, you will find a link to Rinex archives where you can download 24hour files. Again, note data rates and constellations supported.

Individual Local bases. There are many universities that set up permanent bases for various needs, and some cities and counties have set up public bases. Often these have been added to the NGS CORS list, but sometime not. Finding those bases can mean some deep Googling or asking a local GNSS equipment dealer (they often know) or local surveyor. The nature of these bases can vary a lot; there are still some older GIS type bases out there, while other entities have the latest and greatest. How to access these can vary.

Automated base lists can be a great resource but can also be a source of frustration. GNSS manufacturers have set up automated post-processing resources, often for GIS mapping users. These get base data from bases the manufacturer operates, but most often, they just search for openly available base data resources and link to them. Problems arise when such lists are not kept up to date, key details like antenna types that change (i.e., upgrades, stations go out of service, etc.) Users get used to simply hitting the process button and way it goes, often not knowing about the state of the local resources. I’ve seen users processing to a single base a hundred miles distant, not knowing there was a local base only a few miles away that was not added to the lists. Do not bother the local owners of the stations that were added to the auto lists; they are not responsible for updating that proprietary resource (that grabs their data second hand).

It can be a complex situation, and somewhat dynamic. If a user is going to do the serious business of asset mapping, it is worth doing a bit of research into the root sources of the data you are using. If your vendor does not know, then they should quiz the manufacturer to see who is updating the lists. And you can research just what all of the options are in your vicinity. Automation can bring productivity, but not always precision, repeatability, or reliability. Such systems work well but it is often worth a deeper look.

RTN

There are real-time networks covering nearly every state in the U.S., and some partially covering the few that do not have statewide coverage. These vary from public to private to cooperative. There are commercial GNSS manufacturer networks covering substantial parts of the country, as well as commercial regional networks, sometimes operated by equipment manufacturers. That adds up to many thousands of reference stations that are almost without exception logging static data. Find out what resources there are in your vicinity, and what their file access, retention, and archive procedures are.

Archive Compressions

If you find yourself retrieving base files from long-term archives, they may have been compressed to optimize data storage resources. They may have been organized in flat directories by year, Julian date, data rate, then by 24-hour files names with a station name as a prefix. For example: “DERF103i.23d.bz2”. This is 24 hours of observations for station “DERF” for the 103rd day of 2023. Note that the extension is “bz2”; that is a Tar.bz2 file. You can decompress that with just about any zip utility like WinZip or 7-Zip, etc. Once you’ve done that, you might see a file with a “.23d” extension (the number corresponds to the year). That “d” file means it has been pre-compressed with a Hatanaka compression. Many years ago, when we were not spoiled by plentiful and cheap storage options, a brilliant scientist came up with that compression for GPS data. It still exists for a lot of long-term-archived GPS data. To decompress that, you need to run the CNX2RNX executable, either on a command line, or install it on your computer, right click the file you want to decompress, and pick it as the app to open the file with.

Or, to avoid a lot of hassle, secure the base data immediately after you complete the field work. Often the next day is the best option (as some resources may post files overnight). You may not anticipate having to process much later, or reprocessing certain parts of your data, so have those static files on hand while they are readily available. Be prepared.