Every pixel tells a story.

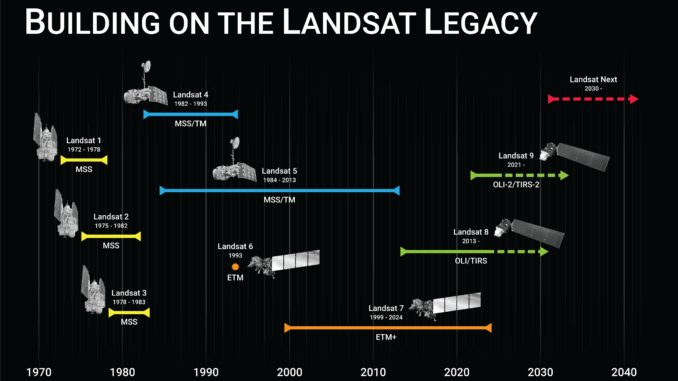

On June 4, 2025, Landsat 7 was officially decommissioned, closing out a mission that spanned more than two decades. Launched in 1999, Landsat 7 carried the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+), adding new capabilities to an already groundbreaking Earth Observation program. Although its nominal science mission ended in 2022, the satellite continued to deliver valuable imagery until January 2024.

On June 4, 2025, Landsat 7 was officially decommissioned, closing out a mission that spanned more than two decades. Launched in 1999, Landsat 7 carried the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+), adding new capabilities to an already groundbreaking Earth Observation program. Although its nominal science mission ended in 2022, the satellite continued to deliver valuable imagery until January 2024.

Today, Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 remain active in orbit, working together as a satellite constellation to image the Earth’s surface every eight days. Together, they carry forward the program’s foundational mission: to provide consistent, scientifically rigorous, and publicly accessible data about our changing planet.

With Landsat 7 now retired, this moment offers a timely opportunity to reflect on what the Landsat program has accomplished since the launch of Landsat 1 in 1972 — and why, over 50 years later, it remains one of the most trusted sources of environmental intelligence in the world.

A Legacy Rooted in Vision

The Landsat program began as a bold experiment. Launched by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), it was the first civilian effort to systematically photograph the Earth’s land surface from space. According to the USGS, Landsat 1 (originally named ERTS-1) carried the Multispectral Scanner System (MSS), a sensor that would revolutionize how scientists understood vegetation, water, and urban change.

Over the years, each Landsat satellite brought technical improvements: Thematic Mapper (TM) sensors, Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+), and eventually the Operational Land Imager (OLI) and Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) aboard Landsat 8 and 9. These sensors enabled greater radiometric precision and atmospheric correction, key features that underpin Landsat’s reputation for reliability.

Why Landsat Still Matters

Despite being modest in resolution (30 meters), Landsat’s strength lies in its consistency and openness. Since 2008, the entire archive, decades of data, has been made freely available, catalyzing a boom in environmental research, national land monitoring programs, and open-source tools. According to NASA, this move democratized Earth observation like never before.

More than just pixels, Landsat offers continuity. It enables time-series analysis that stretches back over 50 years, something no commercial constellation can rival.

The World Through Landsat’s Lens

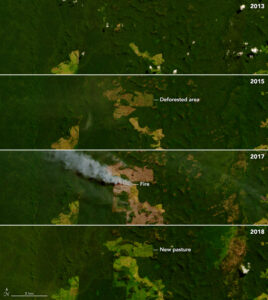

1. Tracking Global Forest Loss

One of the most cited applications of Landsat data is in tracking deforestation. The Global Forest Change project, led by Matt Hansen at the University of Maryland, used over a million Landsat images to produce the first high-resolution global maps of forest cover change from 2000 to 2012.

The result? Governments from Brazil to Indonesia now use Landsat-based platforms to detect illegal logging in near real-time.

2. Mapping Urban Growth

Urban sprawl is one of the most visible transformations on Earth. Cities like Dubai, Accra, and Vancouver have expanded dramatically over the past few decades. Landsat data allows planners to track this growth, assess land conversion, and design smarter infrastructure responses.

3. Agriculture and Food Security

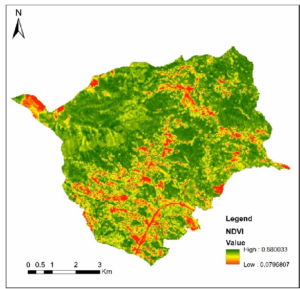

In agriculture, Landsat-derived vegetation indices such as NDVI are widely used to monitor crop health, assess drought conditions, and evaluate irrigation efficiency. The U.S. Department of Agriculture integrates Landsat data into its crop yield forecasting models, while across sub-Saharan Africa, the imagery supports decision-making in farm management, early warning systems, and food security monitoring.

4. Water and Wetlands Monitoring

Landsat’s thermal bands and near-infrared capabilities have been pivotal in tracking shrinking lakes, monitoring wetland ecosystems, and assessing glacial melt. In Canada, Landsat data informs peatland management and watershed health assessments, critical tools for Indigenous land stewardship and federal conservation efforts.

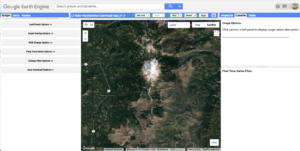

Landsat + Cloud = Open Science

The power of Landsat has only grown with the emergence of cloud platforms. Google Earth Engine, Microsoft Planetary Computer, and Amazon Web Services host petabytes of Landsat data, enabling researchers, students, and NGOs to analyze change over time without downloading a single image.

This has opened doors for global-scale monitoring, from mangroves to megacities, using nothing more than a web browser.

Looking Ahead: Landsat Next

The future of Landsat is already in motion. Landsat Next, scheduled for launch around 2030, promises a generational leap in Earth imaging. Instead of one satellite, it will feature a trio of spacecraft to improve temporal resolution (every 6 days). Spectral resolution will also improve dramatically: 26 bands, including new ones dedicated to water quality, snow, and atmospheric properties.

According to NASA, this advancement will position Landsat Next as an essential tool for global climate policy, environmental enforcement, and precision agriculture.

Landsat is not without its limitations. Cloud cover, especially in tropical regions, can obscure observations. The 16-day revisit time (for Landsat 8 or 9 alone) is relatively long, though this is partially mitigated when both satellites are active.

Commercial providers like Planet or Maxar offer much finer resolution (3–5m or even sub-meter), but at a significant cost and with limited temporal depth. Sentinel-2 from the European Space Agency provides complementary 10m data, but lacks the same archive length and thermal capabilities.

The Watcher We Still Need

For over 50 years, Landsat has quietly captured the Earth’s story, fire scars and forests, floods and farms, cities rising and rivers drying. It is not the flashiest satellite in orbit, but it remains the most trusted.

As environmental challenges intensify and data becomes both politicized and privatized, programs like Landsat represent more than just science, they represent public accountability, planetary memory, and the right to see change.

The world will continue to look down from space. And thanks to Landsat, we will continue to understand what we see.

Be the first to comment