Canada has shown it can move fast when it decides something matters. Artificial intelligence is the proof. The Pan-Canadian AI Strategy, launched in 2017, was the world’s first funded national AI strategy. It built a vibrant national ecosystem by attracting talent, fostering world-class research, and driving collaboration across sectors. Since then, Ottawa has released an AI Strategy for the Public Service (2025–2027) and even created a dedicated Minister of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Innovation.

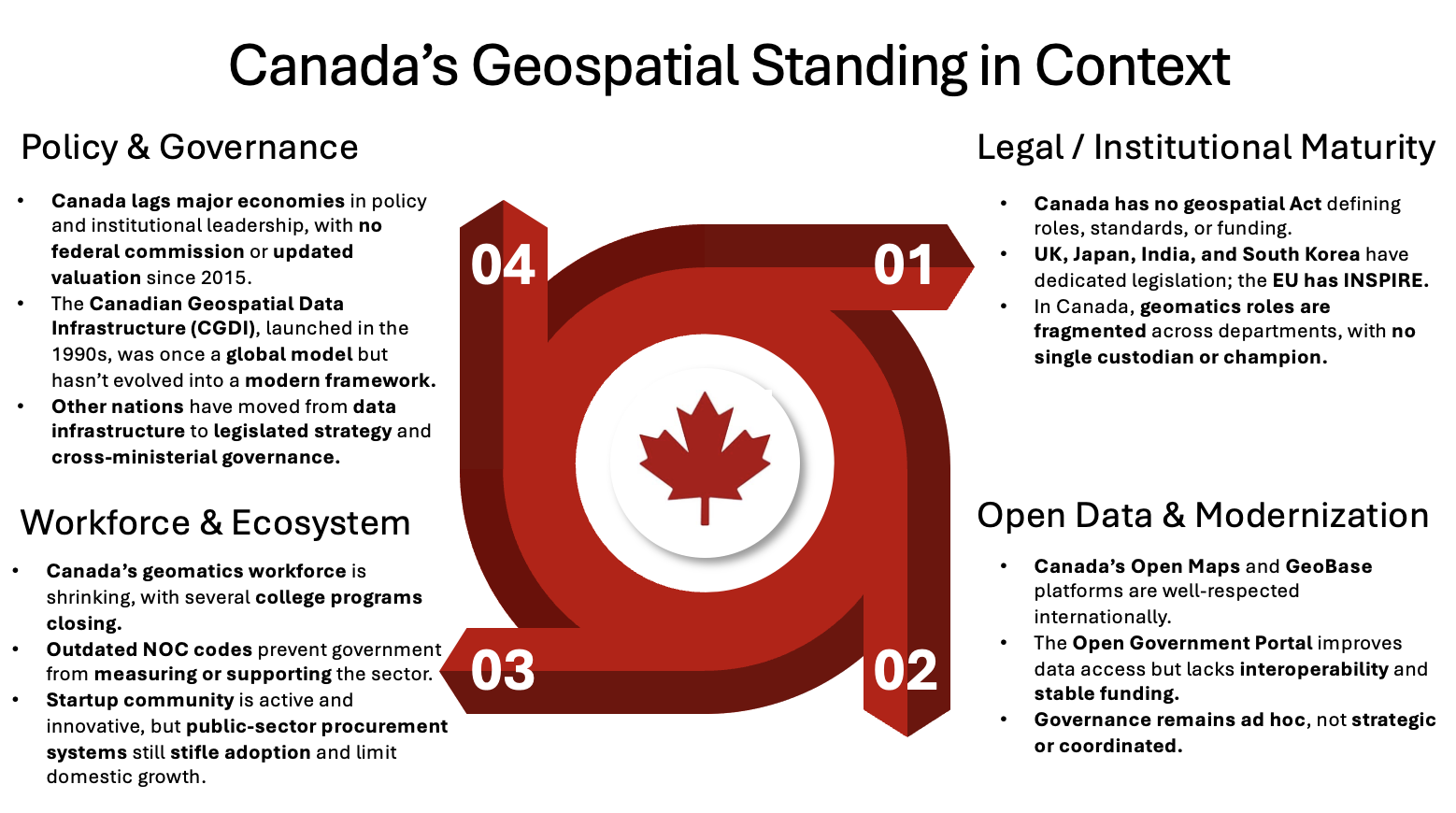

But what about geospatial — the foundation that AI, housing approvals, transit lines, wildfire response, and resilient cities all depend on? Here, Canada has stood still. No national policy. No updated economic valuation since 2015. And no champion in government to drive the cause.

Why this matters now

Canada once stood at the centre of the geospatial world. We are the land where GIS was born, thanks to Roger Tomlinson. We published the world’s first digital atlas and built RADARSAT, proving that this country could lead in data, science, and space technology. Through the late twentieth century, Canada achieved much, but the milestones never connected into a national vision.

The last major effort came with the Canadian Geomatics Environmental Scan and Value Study, launched by Natural Resources Canada and the Canadian Geomatics Community Round Table around 2011–2012 and completed in 2016. It found the geospatial sector contributed $21 billion — 1.1% of GDP — and nearly 19,000 jobs.

At the time, the scan was among the most comprehensive national geospatial assessments produced anywhere.

That study should have been the start of a national strategy. Instead, it became the end of one. Nearly a decade later, others have raced ahead, launching their own value assessments, refining them regularly, and using the results to guide national policy. They have embedded geospatial into their digital economies.

We have left ours stranded in the past. Leadership turned into inertia.

Where Canada faltered

Since 2015, the global geospatial sector has transformed beyond recognition. Earth Observation constellations have multiplied, flooding the world with imagery. Cloud computing and AI now process that data in seconds. IoT sensors turn everything from cars to farms into location-aware devices. Digital twins and smart cities depend on real-time maps of entire systems. And at the heart of it all, positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) technologies have quietly become the invisible infrastructure of the digital economy.

Since 2015, the global geospatial sector has transformed beyond recognition. Earth Observation constellations have multiplied, flooding the world with imagery. Cloud computing and AI now process that data in seconds. IoT sensors turn everything from cars to farms into location-aware devices. Digital twins and smart cities depend on real-time maps of entire systems. And at the heart of it all, positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) technologies have quietly become the invisible infrastructure of the digital economy.

The economic scale of this transformation is staggering. According to Geospatial World’s GeoBuiz 2023 Report, the global geospatial and space economy was worth USD 452 billion in 2022, is projected to reach USD 681 billion by 2025, and will exceed USD 1.44 trillion by 2030. What was once a niche field has become a cornerstone of global digital infrastructure, fuelling everything from logistics and urban planning to climate action and financial systems.

Other countries saw this shift coming and acted. They launched national strategies, updated their valuations, and tied geospatial directly to digital transformation and economic competitiveness.

Canada did not. NRCan still cites the 2015 benchmark — the same figure that once signalled leadership now highlights drift.

The paradox is hard to ignore: a country that once measured its geospatial economy before most others, but never turned that momentum into a sustained national strategy.

Peers that surged ahead

To see how far Canada has drifted, it helps to look at what others have done — both within the G7 and among emerging leaders outside it.

The G7 leaders

- United States: The U.S. has institutionalized geospatial governance through the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) and the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI). In 2023, the U.S. geospatial market was valued at USD 133 billion, with expectations to reach USD 393 billion by 2030.

- United Kingdom: The U.K. established a Geospatial Commission in 2018, placing it in central government and now inside the Government Digital Service. The commission does regular market scans and its 2024 Geospatial Sector Market Report values the sector at over £6 billion annually, supporting more than 37,500 jobs. This cabinet-level anchoring gives geospatial visibility and weight across government — something Canada entirely lacks.

- Germany: Germany integrates geospatial governance into its national digital strategy and aligns federal and state systems through the GeoInformation Federal/State Cooperation framework and the EU INSPIRE Directive. The approach ensures consistent standards and supports its precision manufacturing, logistics, and smart mobility sectors.

- Japan: Japan legislated its approach with the Basic Act on the Advancement of Utilizing Geospatial Information (2007), establishing a national structure for data interoperability and access under the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI).

- France: France is developing a National Spatial Strategy to 2040, linking civil, defence, and industrial priorities. It positions geospatial capabilities as part of the country’s broader sovereignty and digital transformation agenda.

- Italy: Italy operates the Repertorio Nazionale dei Dati Territoriali (RNDT), its national spatial data infrastructure, aligned with EU INSPIRE directives and overseen by the Agenzia per l’Italia Digitale (AgID).

The Non-G7 momentum

Outside the G7, several countries have advanced geospatial policy in deliberate, coordinated ways — treating it as infrastructure, not an afterthought.

- Singapore has made geospatial a whole-of-nation priority. Its Geospatial Master Plan 2024–2033 lays out a decade-long vision connecting land, maritime, and underground data ecosystems.

- South Korea has embedded geospatial in its Act On The Establishment And Management Of Spatial Data and linked it with the country’s digital-government and smart-city agendas. Continuous investment in 3D mapping and national twin infrastructure supports both public services and private innovation.

- The Netherlands is often cited as a global leader in open spatial data. Through Geonovum, it coordinates the implementation of the EU INSPIRE Directive and national open-data standards. The country’s geo-portal and real-time mapping tools underpin decision-making in agriculture, water management, and logistics.

- Australia and New Zealand operate one of the world’s most mature federated spatial governance models through ANZLIC – the Australian and New Zealand Spatial Information Council — supported by the Intergovernmental Committee on Surveying and Mapping (ICSM). Together, they manage the Australian Spatial Data Infrastructure (ASDI) and the New Zealand Geospatial Strategy, ensuring interoperability and consistent standards across jurisdictions.

- India’s National Geospatial Policy (2022) replaced decades of restrictions with a liberalized, innovation-driven framework. It aims to make high-resolution mapping freely accessible, create a national geospatial data registry, and integrate location intelligence into governance and economic development.

- Brazil has emerged as a regional leader with its Infraestrutura Nacional de Dados Espaciais (INDE), coordinated by the IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE). The framework mandates open data standards and public access to national spatial information.

- Mexico has built on its National Statistical and Geographic Information System (SNIEG), operated by INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography), which gives geospatial data the same legal standing as national statistics. This system has become a model for integrating mapping into evidence-based policymaking in Latin America.

- China sits at the other end of the spectrum: a highly centralized system under the Surveying and Mapping Law. Its geospatial industry reached ¥811 billion (≈ USD 115 billion) in 2023, driven by national investments in mapping, GNSS, and satellite infrastructure, according to official government estimates.

Across the G7, every country except Canada now treats geospatial as strategic infrastructure. And even outside the G7 — from Singapore’s whole-of-nation strategy to India’s liberalization and Brazil and Mexico’s legal integration of spatial data — the trend is unmistakable: nations are institutionalizing geospatial as a pillar of governance. Canada remains the outlier.

What’s at Stake for Canada

What’s at stake is not just technology, but the foundations of Canada’s economy, security, and environment.

Economic foundations

Housing, infrastructure, energy, agriculture, and natural resources — the pillars of Canada’s economy — all rest on geospatial foundations. Every road built, house approved, and pipeline maintained depends on accurate spatial data. As Canada commits to massive infrastructure and housing targets, geospatial data is the unseen layer that determines whether projects are delivered on time and within budget.

It’s also where artificial intelligence becomes real: without geospatial, AI is just code. With it, AI can cut approval times, optimise construction and utility grids, and model environmental risk before it becomes a catastrophe.

At the core of this is Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) — the invisible backbone of the modern economy. Every ride-hailing app, bank transfer, aircraft route, farm tractor, and logistics chain relies on it. Yet Canada depends almost entirely on foreign GNSS constellations for this critical service. A disruption in access would cripple key sectors — energy, banking, transport, and communications — as surely as a power blackout.

Defence and sovereignty

Modern security no longer relies solely on ships and aircraft; it relies on the ability to see, map, and understand territory in real-time. From Arctic surveillance to maritime domain awareness, Earth Observation and mapping systems are now central to defence.

As the Arctic warms and new routes open, Russia and China are expanding their polar presence through patrols, exploration, and satellites. Yet, Canada still relies on foreign and commercial data for awareness of the Northern Region. With no coordinated Earth observation strategy and aging assets like RADARSAT-2, the country faces growing blind spots.

Without a sustained national EO and mapping capability, Canada risks ceding informational sovereignty over the very region that defines it. True sovereignty now depends on geospatial intelligence — satellites, data infrastructure, and the policy to connect them.

Environment and climate resilience

Canada is warming twice as fast as the global average, and in the Arctic, nearly four times faster. Melting permafrost, floods, and wildfires are no longer anomalies; they’re the new norm. In 2023 alone, over 18 million hectares burned — the largest wildfire season in recorded history. Geospatial technologies are crucial for monitoring forests, managing water resources, and predicting climate extremes.

From the management of forests and wetlands to the protection of northern ecosystems and coastlines, geospatial intelligence enables resilience. It informs carbon accounting, biodiversity mapping, and emergency response. Without it, Canada cannot credibly meet its climate commitments or safeguard communities from the next major disaster.

What Comes Next

Canada is not starting from zero. NRCan is already leading national consultations on a Canadian Geospatial Data Strategy to modernize the governance and sharing of geospatial data. Coordinated with NRCan, the OGC Canada Forum is fast evolving into an ideal platform that brings government, industry, and academia together to align technical standards and policy toward a coherent national approach.

The Canadian Council of Geomatics (CCOG), now being renewed, could provide a lasting home for national coordination as these frameworks evolve.

Canada also benefits from a strong community network, anchored in the East and West, through GeoIgnite in Ottawa and the GoGeomatics Expo in Calgary, both of which host the Canadian Geospatial and Geomatics Advisory Forum to surface shared priorities.

Beyond events, Canada participates in the ISO mirror committee for geomatics under the Canadian Standards Association, ensuring international standards are reflected domestically. BuildingSMART Canada has shown how a focused national association can drive adoption and standardization — a model that the geospatial industry could follow.

Our geomatics programs remain world-class, yet shrinking enrolments and limited funding put them at risk — a gap that demands urgent attention.

In short, the ingredients exist — but not the recipe, or the chef. For over a decade, Canada has lacked a clear national champion to prioritize geospatial information as a policy objective. The result is a series of strong but disconnected efforts that never add up to momentum. Without leadership, workforce planning stalls, educational pathways narrow, and the opportunity to link geospatial directly to Canada’s trillion-dollar infrastructure build risks being lost.

The choice is straightforward: treat geospatial as an add-on tucked under AI and quantum, or recognize it as a pillar in its own right that enables every digital field.

What Canada needs is clear — a cabinet-level champion, a Canadian Geospatial Commission, a national strategy, and recognition of positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) as critical infrastructure. Without these, coordination remains fragmented and opportunities continue to slip by.

Canada invented modern GIS. It can lead again — if it chooses to.

Be the first to comment