In recent years, high–resolution spaceborne imagery (HRSI), up to 50cm spatial resolution, has become readily available for no cost using such applications as Google Earth and Bing Maps. Thanks to this new availability of free HRSI, numerous types of analysis are now possible using web-based geographic information systems (GIS). Since fully automated extraction of target features has not been realized in many disciplines, manual direct discovery methods of feature identification are still the primary method for identifying new features. This includes the identification of archaeological features or the classification of land cover.

In other disciplines, such as sea ice analysis, much progress has been made in developing and improving algorithms which use dual-polarized synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data to identify sea ice segmentation. Despite these improvements, sea ice maps still require time-consuming human segmentation. Although effective at identifying features, the manual discovery method requires a large commitment of person-hours in the scanning of study areas.

To decrease the cost of the manual direct identification of features and to potentially increase the number of individuals doing analysis, some researchers are turning to crowd-sourcing. Crowdsourcing relies on “a network of interested parties who decide, based on their own interests and their own time, whether they want to help an organization with its problem.” (Gorassi, 2009). Crowdsourcing can allow for organizations to tap into a larger network of workers to complete a task without having to take those workers on as employees or staff.

Coupling freely available HRSI from sources such as Google Earth and ArcGIS.com with the ease of creating Web GIS applications using Java, Flex, or Microsoft Silverlight, allows for web GIS services that specialize in acquiring volunteered geographic information (VGI). Two excellent examples of web GIS services that use VGI are The Geo-Wiki Project and Open Street Maps.

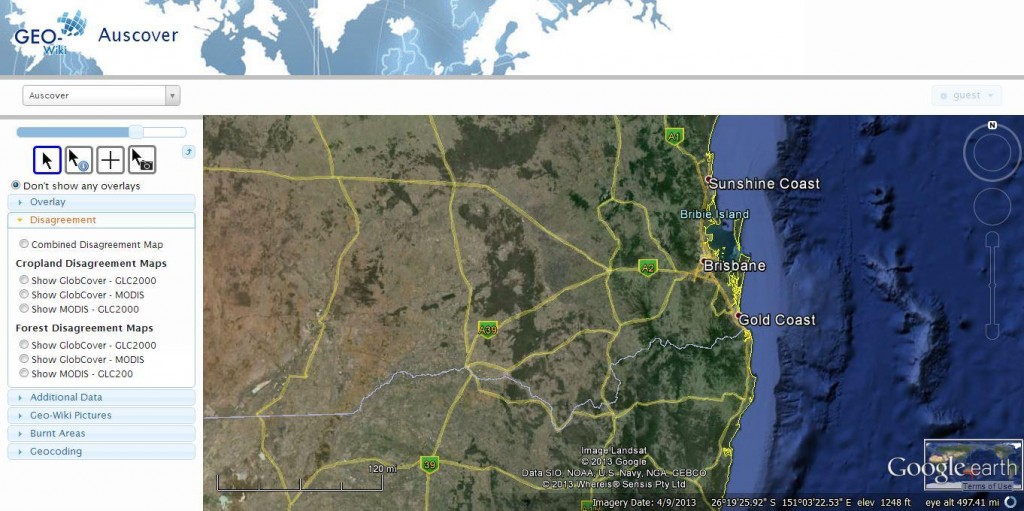

Figure : The Geo-Wiki Project

The Geo-Wiki Project (Figure 1) uses VGI to have users scan through Google Maps imagery. Then, using the imagery and, if applicable, their local knowledge, users update land cover classification. The Geo-Wiki Project currently focuses on areas where there are disagreements in existing land cover maps. Users are able to upload photos as well as classify land cover. In addition to land cover classification, the project has been expanded to include: agriculture coverage, human impact assessment, urban development, and archaeological exploration. In 2011, Margaret Brown Vega published, “Ground truthing of remotely identified fortifications on the Central Coast of Peru” in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Here, she outlines her usage of Google Earth imagery in the identification of archaeological sites prior to field exploration. Her work, along with the Geo-Wiki Project, shows that VGI and remote sensed imagery can be used in scientific explorations.

VGI: the Wild West of Data.

As VGI continues to grow, the challenges associated with incorporating it into existing, trusted datasets are being resolved. In 2012, Natural Resources Canada’s GeoConnections program released “Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) Primer” as part of the Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure (CGDI) on-line resource. This primer offered great insight into the benefits and potential drawbacks of using VGI, focusing on “data quality and authoritativeness, legal realities, archiving and preservation, and security” (Natural Resources Canada, 2012). This information should be referenced before including VGI in any research.

As VGI becomes more widely used, researchers from many disciplines are incorporating it into their research. One interesting use of VGI is to provide a control map that automated processes can be tested against. For example, better algorithms are being developed which use SAR to identify sea ice. Testing these algorithms against their predecessors reveals the difference between them. This will not, however, identify features that both algorithms failed to identify or mistakenly identified. Using VGI, a base map can be created which can be used to compare the automatic extraction from manual identification (Yu, 2009).

As more researchers and government agencies begin to incorporate VGI, procedures to handle concerns regarding quality, ownership, and stewardship are being rectified. Sources such as CGDI at Natural Resources Canada and Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic have created great tools for researchers planning to incorporate VGI. With Web APIs such as Google Earth and ESRI’s ArcGIS API for JavaScript becoming easier to deploy, acquiring VGI has never been easier. Although VGI has the potential to be a great new data source for many projects, researchers should not incorporate it without fully understanding both its benefits and its limitations.

References:

Brown Vega, M (2011). “Ground truthing of remotely identified fortifications on the Central Coast of Peru”. Journal of archaeological science (0305-4403), 38 (7), p. 1680-1689.

Gorassi, Angie (2009). “Got a problem? ‘Crowdsource’ it”. Canadian HR reporter (0838-228X), 22 (15), p. 34

Natural Resources Canada (2012) “Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure Information Product 21e: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) Primer”. Ottawa, Ontario Canada. P18.

Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic. “Volunteered Geographic Information.” https://cippic.ca/FAQ/vgi . Accessed November 1, 2013.

Yu, Peter (2009). “Segmentation of RADARSAT-2 Dual-Polarization Sea Ice Imagery”. Thesis, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

Be the first to comment