There seems to be great confusion between these two great disciplines, especially noting that some geographers and schools claim that Geomatics is a geographical science when it is not. There has been a general confusion over the term Geomatics since its adoption in the mid-eighties. Let’s look at some general definitions one can find on the web to help understand the matter.

Geomatics (from the University of New Brunswick) comprises the science, engineering, and art involved in collecting and managing geographically-referenced information. There are some typical specializations:

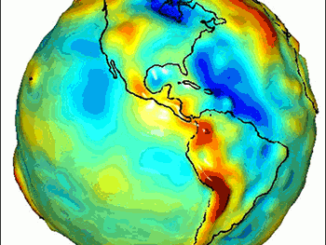

- Geodesy is the science of mathematically determining the size and shape of the earth and the nature of the earth’s gravity field.

- Cadastral work consists of geodetic and engineering surveys, survey law, land use planning, hydrographic surveying, and skills required for determining property boundaries and the measurement and analysis of land related information.

Geography (from the University of Calgary) focuses on places and spaces, on humankind’s stewardship of the Earth, and on the inter-related problems associated with urban, environmental, economic, political, and cultural change.

Geography as a discipline can be split broadly into two main fields:

- Human geography – focuses on the built environment and how humans create, view, manage and influence space.

- Physical geography – which examines nature and how life, climate, soil, water and landforms produce and interact.

So though geography and Geomatics do overlap, Geomatics is an engineering applied science involving measurement of the earth whereas geography is a social or humanities science studying human influences on the earth.

One point of confusion is that both fields use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to display and analyze data. A misnomer that exists (and is the fault of many schools that market GIS programs) is that GIS is a profession, when it is truly a toolset. For example, there are many people with the title ‘GIS Analyst’ when really they are geologists or archaeologists or geographers or surveyors or some other kind of specialists who happen to use GIS as a part of their work.

Lately the term “geospatial” has also become popular, muddying the waters even further. To break down the term, ‘geo’ is of or relating to the earth and Spatial is of or relating to space, or more specifically relating to the position, area or size of things.

Therefore, geospatial has to do with relating geographic position and characteristics of features on, above or below the earth’s surface. Based on that, geospatial rightfully belongs more fully in the domain of Geomatics as pertains to measurements. Geography also measures, but only to support the study of human interactions, not for measurement for the purposes of engineering. An adage that is floating around states that 80% of all data has a spatial component. Therefore, it is important to understand spatial relationships from an engineering point of view via Geomatics and for the human perspective via Geography. One can analyze the data from either perspective with GIS, especially as GIS is great for connecting non-spatial data with spatial data and can generate unique realizations of the data once it has been spatialized. For example, take a highway network. From a Geomatics perspective, one would be interested in the slope of the crown of the road for drainage and the radii of curvature and superelevations of the curves to allow safe transit by vehicles as well as the ability to survey such a road for the purpose of construction. Geography would be more interested in the network capability and the ability of such a roadway to convey people from one point to another.

So why do I even bother to try to differentiate these fields? Geomatics, being a relatively new term, has suffered an identity crisis – most people have no idea what it is. Mention survey engineering or civil engineering (as survey is technically a specialization of civil), and people envision someone with GPS or a total station out measuring something. And because the field of surveying is a rare exception to be an engineering discipline with its own exclusive practice (most engineering acts specifically exclude the act of surveying as its own form of engineering) it is a very small, but important, niche market that attracts employees that like to calculate and work outdoors in oftentimes harsh environments.

Being a reviewer for my local professional association over the years, a number of people that have a geography-based or GIS-based background have applied for professional credentials in the hopes of securing a professional Geomatics designation. Unfortunately, there generally is not enough overlap between Geomatics and their own backgrounds for which they are routinely denied the desired credentials to their great frustration. They are generally offered reclassifications to upgrade their skillsets, which typically involves completing additional engineering-related training and/or experience. Although I can empathize with these applicants, the proper relevant skillsets must be in place in order to achieve such a credential.

So in the end, although there is much overlap between tools used by practitioners of Geomatics and geographers (GIS, remote sensing, GPS, etc.), one must carefully distinguish that these two fields are significantly different enough that they cannot be considered the same. Not that we can’t all work together to get things done.

Be the first to comment