The Research Mission

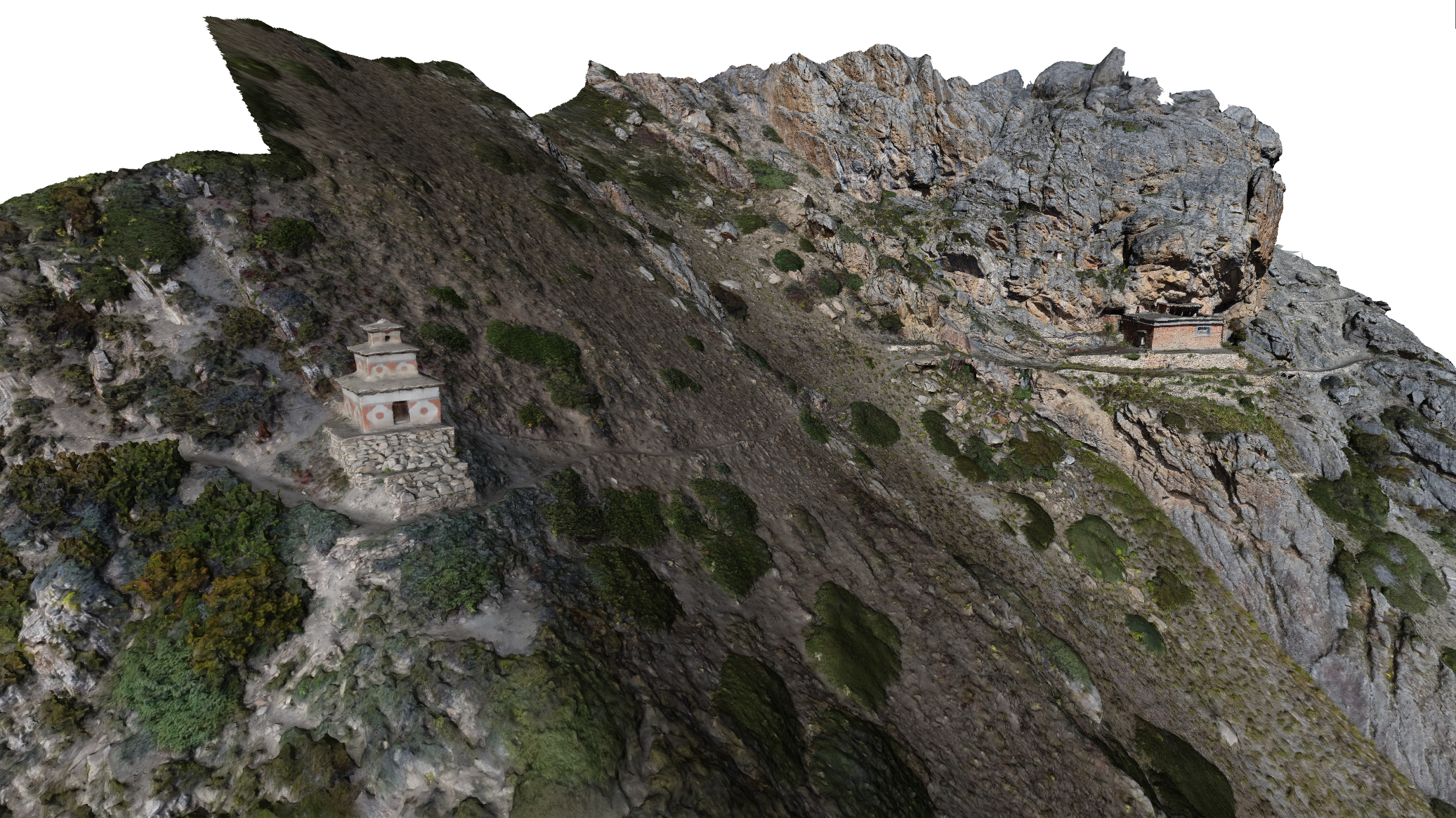

The Nezar Temple has stood in the village of Bijer for over nine centuries and is among the oldest Buddhist monasteries outside of Tibet. Bijer, with a present population of 250, is in the remote Upper Dolpo region of Nepal; an area that had, until two centuries ago, had been encompassed by Tibet. In addition to the gompa (a structure for meditation and learning), there are twenty-two stupas: mound-shaped sepulchral monuments (a place of burial or a receptacle for religious objects). It is one of several similar sites mapped—and 3D modelled—during a recent two-month long academic expedition.

The joint expedition, mounted by the Institute of Engineering Geodesy and Measurement Systems and the Institute Architectural Theory, History of Art and Cultural Studies of the Technical University of Graz (TU-Graz) Austria, was part of the ongoing Austrian Science Foundation (FWF) project: “Buddhist Architecture in the Western Himalayas”. With a goal of supporting research into understanding the evolution of architectural styles and techniques through history, the addition of high-definition 3D laser scanning data provided details and insights thus far unavailable to researchers.

Packing It In

“To reach the villages of Upper Dolpo, you have to take two airplanes, and then form a caravan; hiking in with pack mules for several days,” said Peter Bauer, university assistant and doctoral candidate at TU-Graz. While there were measurements of these sites from the past, these were tape measured with hand notes, or at best, with a total station. When the joint expedition announced that they would employ a laser scanner and drone, this was met with great excitement by the researchers.

“We had to be very cautious in planning what equipment and instruments to bring,” said Bauer. “The Leica RTC360 was our scanner of choice as it is easy to transport and very light —and was a good compromise between the Leica ScanStation P50—too big for this expedition—and a Leica BLK360. The BLK360 would have been great for the small interior areas, but we found the RTC360 much better for the extensive exterior scans we would need to do.”

Getting It Right the First Time

While reality capture and 3D modelling have become commonplace, this Nepal project exemplifies the uncommon. Key to overcoming multiple challenges was the power of the in-field registration and on-the-spot quality assurance features of the Leica Geosystems RTC360 and Cyclone FIELD 360 software. The project team had one shot to get it all right, and the solutions they employed made all the difference.

This 2-month project was performed in areas with limited power and no internet; luxuries most reality capture practioners take for granted. With the help of Cyclone FIELD 360, the scans were progressively registered when moving from setup to adjacent setup. With further quality assurance steps taking place while at the sites, in Cyclone REGISTER 360 PLUS on a laptop.

Contrast this with legacy methods: ad hoc measurements with tapes, sketches, total stations, and field notes; all to be compiled and analysed after-the-fact. Even when legacy scanners are utilised, there could be further steps to register the point clouds and constrain the targets. These steps were mostly done later in the office. This meant that errors and omissions would not be caught until it was too late, only to be reconciled by a return to the site. In the case of this Nepal scanning project, going back was not a practical option—it all had to be right the first time.

Common Ground

The initial step, prior to scanning, was establishing control as a base framework for scan setups and aerial targets. “This was very important, as these sites were also to be studied for structural stability,” said Bauer. “We needed to capture the load-bearing features: walls, columns and pillars. And very precisely relative to all other structural elements.” At each site, there were around 50 scan setups for the interior of each monastery, with another 50 outside, capturing about 3.5 GB of point cloud data for each setup.

“With Cyclone FIELD 360, we could register the scans to each other automatically as we went along through the setups,” said Bauer. “And to tag the targets in the field, which helped a lot for the post-processing because we simply couldn’t import all of the other datasets right away.” Later, the team produced mesh-models, and textured mesh models to pass on to the architects, to perform the structural investigation, loading the models into their own software for analysis. “Being able to export standard format data files worked well for our primary goal,” said Bauer. “To create a 3D model, and then multiple derivatives.”

There were concerns about lighting, as the structures were not well lit. “The RTC360 could pick up a lot of detail, even in limited light, but we needed just a little bit more of a light boost,” said Bauer. “We each had carried helmet torches. By fashioning plastic bubbles over them to diffuse the beam, we got just what we needed.”

Bridging Cultures

These are among the holiest sites in the region, with deep cultural meaning and a sense of identity and pride for the local residents. While visiting researchers are mostly greeted more amicably than tourists, the team had to proceed respectfully and assure the residents, for instance, that the scans would not be capturing sensitive details. “There have been issues with theft at some sites, and the locals do not want the treasured contents of their temples broadcast to the world,” said Bauer. “However, as we were able to quickly show the 3D models, the locals began to see this as a great tool for documenting and preserving.”

“The local community was very impressed with being able to fly around in the 3D model, even seeing things from above the ground,” said Bauer. By bonding over the scans, and establishing mutual purpose, the team got to share a bit of local life. “Staying at the temple, sitting together in the kitchen, seeing people come and go, getting invited for food—this was truly one of the best experiences.”

Bauer said that they also found a great admiration for the local community, and their resilience living in such a remote, sometimes harsh, high latitude environment. “While travelling on foot with our caravan, an elderly local woman carrying a heavy sack of rice decided to walk along with us. However, after a short while she went on without us, saying that if she had to walk at our slow pace, she would be late by days.”

Be the first to comment